I've been reluctant to respond to the Five Things You Didn't Know About Me meme. I generally take Kathy Sierra's advice when it comes to describing my background:

How many talks do you see where the speaker has multiple bullet points and slides just on their background? I did it once because I thought it would help people understand the context of my talk, and it did NOT go over well because:

A) Nobody cares.

B) Bullet points do not equal credibility.

C) Nobody cares.

D) You already HAVE credibility going in... you don't have to earn it, you just have to make sure you don't lose it.

E) Nobody cares.

And then there's Hugh MacLeod's take on the Five Things:

1. I dislike you intensely.

2. I love it when bad things happen to you.

3. When your name is mentioned I immediately try to change the subject.

4. I wouldn't read your blog if you paid me.

5. If we were trapped on a desert island together I would kill myself.

It's funny. But it's not really a response to the question. People have shared so generously with the Five Things post, and they've gone out of their way to express an interest in others by tagging them. It would be rude not to respond in kind with equal generosity. Although it's technically off topic, Five Things has made for strangely compelling reading.

I like to think that the important part of my blog is the content, not me. After all, users don't care about me. It's about what you, the reader, get out of this blog. I struggled with this for a while until I realized what I was missing. Blogs, for better or worse, are as much about the writer as they are any other topic. Personality is the essential ingredient that makes blogs so interesting, so compelling, so.. human. To avoid writing about yourself is just as much of a mistake as writing about yourself in every post. So Five Things isn't off topic at all. It's very much on topic. Behind every fascinating blog is a fascinating person.

With that in mind, I thought I'd offer a small pictorial tour of my office at Vertigo Software. It's as much a reflection of my personality as anything else in my life.

Here's the entrance to my office. As you can see, Vertigo does treat developers in accordance with the Programmer's Bill of Rights. The Aeron chair is standard issue to protect developers' second most important asset.

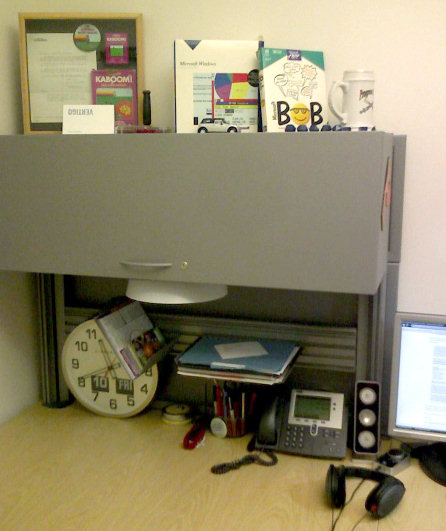

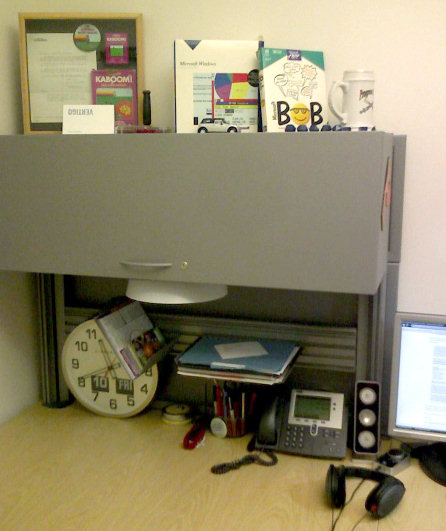

I like to keep new and interesting items on the front table for visitors to play with, and to attract people into my office. Here's what I have out on the front table right now:

I also have iridescent thinking putty out permanently. I love putty. It's my absolute all time favorite desk tcotchke. And it's practical, too. As I noted last year, putty is legitimate exercise for your hand and your brain. I can't recommend it highly enough. I like it so much that I took it upon myself to buy every new Vertigo employee a tin of their very own thinking putty in a unique color.

Here's a closeup of the back wall. The items on the wall aren't art, but wrapping paper from Knock Knock, the same company behind the flash cards. I spray-mounted them on foamcore backing for a drop-shadow effect and attached them with 3M's amazing Command picture mounting strips. I can't find a link to the wrapping paper on their site any more, so I'm not sure if they still sell it. But each one is a little inside joke:

- the colorized DNA sequence on the left is the gene for color blindness.

- the barcode is the actual barcode for the actual wrapping paper itself.

- the fingerprint belongs to the person who designed the wrapping paper.

Also on the table are some of my other favorite things: a three-dimensional color cube, a "museum size" chrome Tangle, and a cheap, generic digital picture frame that I mounted into a fancy gold leaf frame and matted with black construction paper. Trust me, the original frame was hideously ugly. I usually leave the picture frame running The Office (BBC) episodes 1 and 2 encoded into Xvid on a 512mb SD card. I also have Airplane! and Raising Arizona (among others) encoded in the same format, and I swap them out occasionally. I'm a big movie fan, so it's moving art to me.

Here's my computer. I built it myself. You can see a glimpse of it in the first picture under my desk; it's a green Asus Vento. As I've mentioned many times before, I use three monitors at home and at work. The Logitech MX518 satisifies my mouse fetish, and the Microsoft Natural Keyboard 4000 is, as far as I'm concerned, the Keyboard of the Gods. It just doesn't get any better than that rich corinthian naugahyde under your palms. The speakers are mostly for show; you can see the Sennheiser Headphones I swear by on the left-hand side.

Directly above my monitors is my pride and joy: my very own Pong clock. I'm fascinated with clocks, so the Pong clock was my holy grail: it mixes art with classic video games, and it's a functional clock, too. I waited six months to get this delightful piece of art, and every day was worth it. Every minute the right side wins. Every hour the left side wins. Forever.

Here's a closeup of my bobblehead ninja. I can't stop thinking about ninjas. You can also see my small collection of Kikkerland windups in the background behind the monitors. It's fun to wind these things up and watch them grind around, to temporarily leave the digital world behind and revel in the purely analog.

To my left and behind me, I have a few other items of interest. On the lower level, from left to right:

- A Kikkerland wall clock, one of my favorites, but quickly demoted after the Pong Clock arrived.

- Some Visibone cheatsheets. As if you needed any more evidence that I cheat my way to the top.

- A Swiss Business Tool, so I am ready for any business situation that might befall me. Businesspeople beware!

- A mug boss to organize my archaic writing implements. I also own its big brother, the bucket boss, for my tools.

On the upper level, from left to right:

Here's a shot directly in front and to the left of my desk. I've always wanted a mobile in my office. This one is from flensted. It's always moving, and as far as I'm concerned, it's the next best thing to having a window overlooking the ocean. The art on the wall is cheap stuff from IKEA that caught my eye. My wife and I are huge IKEA fans. When we lived in North Carolina, the closest IKEA was in Baltimore, more than 5 hours away. Going there was a rare pleasure. Here in California, there's an IKEA barely 15 minutes away, so we can go any time we want. Life is sweet.

On the other wall, I have a standard-issue whiteboard, along with more inexpensive wall art from IKEA. Above the whiteboard is my BetaBrite LED sign. I use the .NET API I wrote for the BetaBrite to route the current weather conditions and top RSS news feeds to it.

And that concludes my office tour. But in the spirit of Five Things, I'll go even further. Here are five things you didn't know about me:

- I do not own any jeans, or any denim clothing whatsoever. I had enough denim in high school to last the rest of my life. I'm done with that.

- I was arrested for wardialing and phreaking by a small telco in 1987. They even tapped my phones and everything. I used a program I wrote in AmigaBasic to repeatedly dial numbers and guess calling codes. Luckily I had been away for high school senior beach week during part of the investigation, so I hadn't been running the program as much. Since I had no prior record, with the help of a lawyer, I was able to get the charges dropped. And yes, I stopped doing that. In the dark ages before the internet, all we had were BBS systems and modems. And long distance charges were incredibly expensive back then. To get your BBS fix, you had to find some way around the long distance charges. I'm glad today's kids don't face the same dilemma.

- I am terrible at math. How terrible, you ask? Well, I thought I might head off to business school in 1994 so I took the GREs. This was the first standardized test I actually studied for. Not because I'm so smart, mind you, but because I'm very, very lazy. With the additional effort of studying, I did my best on the tests: I scored in the 99.9th percentile on the verbal part of the GRE, but barely made 77th percentile in math. This has always bugged me, because computers and math are so closely linked. I love computers, but I can't stand math. No matter how hard I apply myself, I'm terrible at it. I could never quite wrap my brain around the concepts. But I'm really good at writing about how much I suck at math, for what that's worth.

- I met my wife on the dance floor during 80's night. There I was, minding my own business, getting my groove on to The Safety Dance at this club in Denver in April 1994. As I'm dancing, I suddenly felt a tap on my shoulder. I turned around and there was this cute girl telling me "you're doing it wrong". As in, I was doing the Safety Dance wrong. I thought it was just a song; who knew it was an actual dance? Live and learn. That may be why, to this day, I still have an obsessive love for 80's music. I probably own 60-70 discs worth of 80's song collections (including remixes), and I listen to it regularly.

- I don't really even like computers. Just kidding. My wife often tells me, half-jokingly, that I love computers more than I love her. Of course that's not true. Love is an awfully strong word. But I do think I'd have sex with my computers if it was physically possible.

I'm tagging my Vertigo Software coworkers who blog in the hope that they'll share five things about themselves, too: Eric Cherng, Scott Stanfield, Alan Le, Dan Swearingen, and last but most of all least, Matt Hempey.

Discussion