Your Password is Too Damn Short

I’m a little tired of writing about passwords. But like taxes, email, and pinkeye, they’re not going away any time soon. Here’s what I know to be true, and backed up by plenty of empirical data:

- No matter what you tell them, users will always choose simple passwords.

- No matter what you tell them, users will re-use the same password over and over on multiple devices, apps, and websites. If you are lucky they might use a couple passwords instead of the same one.

What can we do about this as developers?

- Stop requiring passwords altogether, and let people log in with Google, Facebook, Twitter, Yahoo, or any other valid form of Internet driver’s license that you’re comfortable supporting. The best password is one you don’t have to store.

- Urge browsers to support automatic, built-in password generation and management. Ideally supported by the OS as well, but this requires cloud storage and everyone on the same page, and that seems most likely to me per-browser. Chrome, at least, is moving in this direction.

- Nag users at the time of signup when they enter passwords that are…

- Too short:

UY7dFd - Lack sufficient entropy:

aaaaaaaaa - Match common dictionary words:

anteaters1

- Too short:

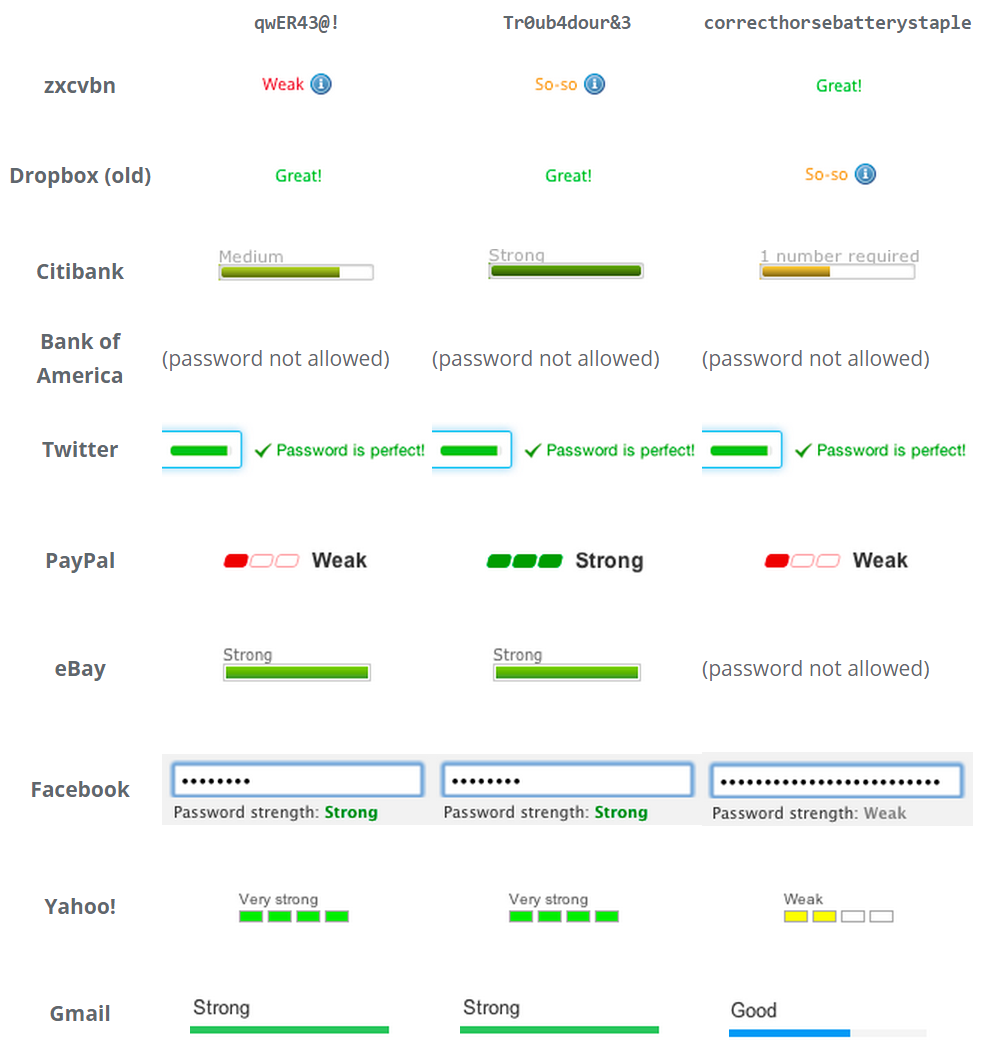

This is commonly done with an ambient password strength meter, which provides real time feedback as you type.

If you can’t avoid storing the password – the first two items I listed above are both about avoiding the need for the user to select a ‘new’ password altogether – then showing an estimation of password strength as the user types is about as good as it gets.

The easiest way to build a safe password is to make it long. All other things being equal, the law of exponential growth means a longer password is a better password. That’s why I was always a fan of passphrases, though they are exceptionally painful to enter via touchscreen in our brave new world of mobile – and that is an increasingly critical flaw. But how short is too short?

When we built Discourse, I had to select an absolute minimum password length that we would accept. I chose a default of 8, based on what I knew from my speed hashing research. An eight character password isn’t great, but as long as you use a reasonable variety of characters, it should be sufficiently resistant to attack.

By attack, I don’t mean an attacker automating a web page or app to repeatedly enter passwords. There is some of this, for extremely common passwords, but that’s unlikely to be a practical attack on many sites or apps, as they tend to have rate limits on how often and how rapidly you can try different passwords.

What I mean by attack is a high speed offline attack on the hash of your password, where an attacker gains access to a database of leaked user data. This kind of leak happens all the time. And it will continue to happen forever.

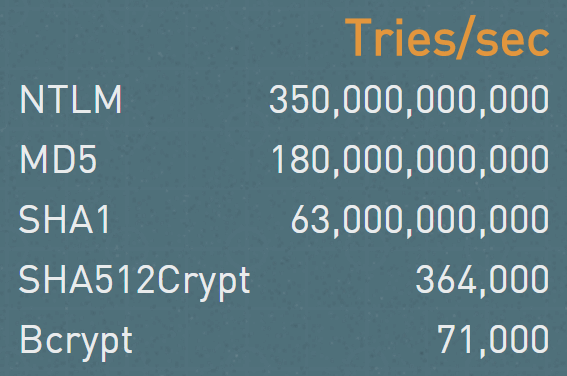

If you’re really unlucky, the developers behind that app, service, or website stored the password in plain text. This thankfully doesn’t happen too often any more, thanks to education efforts. Progress! But even if the developers did properly store a hash of your password instead of the actual password, you better pray they used a really slow, complex, memory hungry hash algorithm, like bcrypt.* And that they selected a high number of iterations. *Oops, sorry, that was written in the dark ages of 2010 and is now out of date. I meant to say scrypt. Yeah, scrypt, that’s the ticket.

Then we’re safe? Right? Let’s see.

- Start with a truly random 8 character password.

Note that 8 characters is the default size of the generator, too.(update: default of 12 characters) I gotU6zruRWL. - Plug it into the GRC password crack checker.

- Read the “Massive Cracking Array” result, which is 2.2 seconds.

- Go lay down and put a warm towel over your face.

You might read this and think that a massive cracking array is something that’s hard to achieve. I regret to inform you that building an array of, say, 24 consumer grade GPUs that are optimized for speed hashing, is well within the reach of the average law enforcement agency and pretty much any small business that can afford a $40k equipment charge. No need to buy when you can rent – plenty of GPU equipped cloud servers these days. Beyond that, imagine what a motivated nation-state could bring to bear. The mind boggles.

Even if you don’t believe me, but you should, the offline fast attack scenario, much easier to achieve, was hardly any better at 37 minutes.

Perhaps you’re a skeptic. That’s great, me too. What happens when we try a longer random.org password on the massive cracking array?

| 9 characters | 2 minutes |

| 10 characters | 2 hours |

| 11 characters | 6 days |

| 12 characters | 1 year |

| 13 characters | 64 years |

The random.org generator is “only” uppercase, lowercase, and number. What if we add special characters, to keep Q*Bert happy?

| 8 characters | 1 minute |

| 9 characters | 2 hours |

| 10 characters | 1 week |

| 11 characters | 2 years |

| 12 characters | 2 centuries |

That’s a bit better, but you can’t really feel safe until the 12 character mark even with a full complement of uppercase, lowercase, numbers, and special characters.

It’s unlikely that massive cracking scenarios will get any slower. While there is definitely a password length where all cracking attempts fall off an exponential cliff that is effectively unsurmountable, these numbers will only get worse over time, not better.

So after all that, here’s what I came to tell you, the poor, beleagured user:

Unless your password is at least 12 characters, you are vulnerable.

That should be the minimum password size you use on any service. Generate your password with some kind of offline generator, with diceware, or your own home-grown method of adding words and numbers and characters together – whatever it takes, but make sure your passwords are all at least 12 characters.

Now, to be fair, as I alluded to earlier all of this does heavily depend on the hashing algorithm that was selected. But you have to assume that every password you use will be hashed with the lamest, fastest hash out there. One that is easy for GPUs to calculate. There’s a lot of old software and systems out there, and will be for a long, long time.

And for developers:

- Pick your new password hash algorithms carefully, and move all your old password hashing systems to much harder to calculate hashes. You need hashes that are specifically designed to be hard to calculate on GPUs, like scrypt.

- Even if you pick the “right” hash, you may be vulnerable if your work factor isn’t high enough. Matsano recommends the following:

- scrypt:

N=2^14, r=8, p=1 - bcrypt:

cost=11 - PBKDF2 with SHA256:

iterations=86,000

But those are just guidelines; you have to scale the hashing work to what’s available and reasonable on your servers or devices. For example, we had a minor denial of service bug in Discourse where we allowed people to enter up to 20,000 character passwords in the login form, and calculating the hash on that took, uh… several seconds.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I need to go change my PayPal password.