Let’s Play Planning Poker!

One of the most challenging aspects of any software project is estimation – determining how long the work will take. It’s so difficult, some call it a black art. That’s why I highly recommend McConnell’s book, Software Estimation: Demystifying the Black Art; it’s the definitive work on the topic. Anyone running a software project should own a copy. If you think you don’t need this book, take the estimation challenge: how good an estimator are you?

How’d you do? If you’re like the rest of us, you suck. At estimating, I mean.

Given the uncertainty and variability around planning, it’s completely appropriate that there’s a game making the rounds in agile development circles called Planning Poker.

There are even cards for it, which makes it feel a lot more poker-ish in practice. And like poker, the stakes in software development are real money – although we’re usually playing with someone else’s money. If you have a distributed team, card games may seem like a cruel joke. But there’s a nifty web-based implementation of Planning Poker, too.

Planning Poker is a form of the estimation technique known as Wideband Delphi. Wideband Delphi was created by the RAND corporation in 1968. I assume by Delphi they’re referring to the oracle at Delphi. If anything says “we have no clue how long this will take,” it’s naming your estimation process after ancient, gas-huffing priestesses who offered advice in the form of cryptic riddles. It doesn’t exactly inspire confidence, but that’s probably a good expectation to set, given the risks of estimation.

Planning Poker isn’t quite as high concept as Wideband Delphi, but the process is functionally identical:

- Form a group of no more than 10 estimators and a moderator. The product owner can participate, but cannot be an estimator.

- Each estimator gets a deck of cards: 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 20, 40, and 100.

- The moderator reads the description of the user story or theme. The product owner answers brief questions from the estimators.

- Every estimator selects an estimate card and places it face down on the table. After all estimates are in, the cards are flipped over.

- If the estimates vary widely, the owners of the high and low estimates discuss the reasons why their estimates are so different. All estimators should participate in the discussion.

- Repeat from step 4 until the estimates converge.

There’s nothing magical here; it’s the power of group dialog and multiple estimate averaging, delivered in an approachable, fun format.

Planning Poker is a good option, particularly if your current estimation process resembles throwing darts at a printout of a Microsoft Project Gantt chart. But the best estimates you can possibly produce are those based on historical data. Steve McConnell has a whole chapter on this, and here’s his point:

If you haven’t previously been exposed to the power of historical data, you can be excused for not currently having any data to use for your estimates. But now that you know how valuable historical data is, you don’t have any excuse not to collect it. Be sure that when you reread this chapter next year, you’re not still saying “I wish I had some historical data!”

In other words, if you don’t have historical data to base your estimates on, begin collecting it as soon as possible. There are tools out there that can help you do this. Consider the latest version of Fogbugz; its marquee feature is evidence-based scheduling. Armed with the right historical evidence, you can...

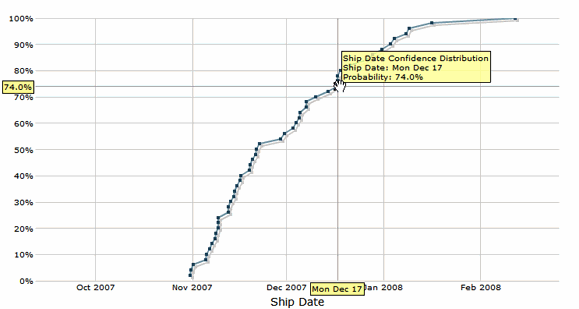

Predict when your software will ship. Here you can see we have a 74% chance of shipping by December 17th.

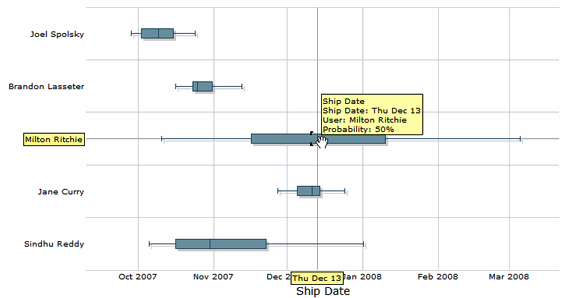

Determine which developers are on the critical path. Some developers are better at estimating than others; you can shift critical tasks to developers with a proven track record of meeting their estimates.

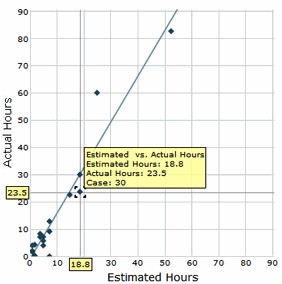

See how accurate an estimator you really are. How close are your estimates landing to the actual time the task took?

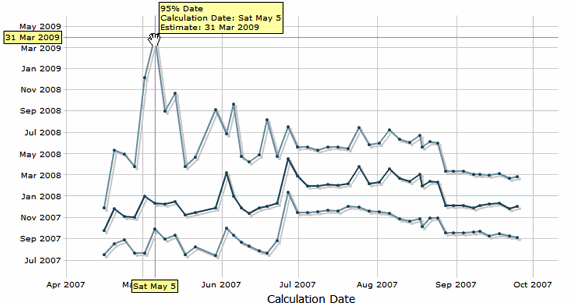

See your predicted ship dates change over time. We’re seeing the 5%, 50%, and 95% estimates on the same graph here. Notice how they converge as development gets further along; this is evidence that the project will eventually complete, and you won’t be stuck in some kind of Duke Nukem Forever limbo.

Witness, my friends, the power of historical data on a software project.

The dirty little secret of evidence based scheduling is that collecting this kind of historical data isn’t trivial. Garbage in, garbage out. It takes discipline and concerted effort to enter the effort times – even greatly simplified versions – and to keep them up to date as you’re working on tasks. Fogbugz does its darndest to make this simple, but your team has to buy into the time tracking philosophy for it to work.

You don’t have to use Fogbugz. But however you do it, I urge you to begin capturing historical estimation data, if you’re not already. It’s a tremendous credit to Joel Spolsky that he made this crucial feature the centerpiece of the new Fogbugz. I’m not aware of any other software lifecycle tools that go to such great lengths to help you produce good estimates.

Planning Poker is a reasonable starting point. But the fact that two industry icons, Joel Spolsky and Steve McConnell, are both hammering home the same point isn’t a coincidence. Historical estimate data is fundamental to the science of software engineering. Over time, try to reduce your reliance on outright gambling, and begin basing your estimates on real data. Without some kind of institutional estimation memory – without appreciating the power of historical data – you’re likely to keep repeating the same estimation errors over and over.