The Cognitive Style of Visual Studio

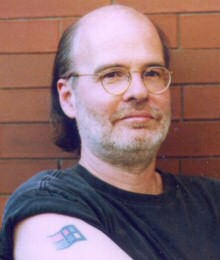

Charles Petzold is widely known as the guy who put the h in hWnd. He’s the author of the seminal 1988 book Programming Windows, now in its fifth edition. And he can prove it, too. He has an honest-to-God Windows tattoo on his arm:

This is explained in his FAQ:

Q. Is that a real tattoo?

A. I think of it more as a scar I got after doing Windows programming for ten years (beginning in 1985).

When Charles Petzold talks, with my apologies to E.F. Hutton, people listen. Charles recently spoke at the NYC .NET Developer’s Group and asked, Does Visual Studio Rot the Mind?

It’s a great essay. The central idea is that your skillset should not be dictated by the tools you use. I’ve covered similar ground in Programming for Luddites, so I don’t necessarily disagree. But I also wonder if Petzold has fallen into the trap Dan Appleman outlines in RAD is not productivity:

The reason that so much bad VB6 code was written was not because VB6 was RAD, but because it was easy. In fact, VB6 made writing software so easy that anyone could be a programmer, and so everyone was. Doctors, Lawyers, Bankers, Hobbyists, Kids – everyone was writing VB6 code with little or no training.

Now, I don’t know about you, but I still have copies of a few of the programs I wrote when I was just starting out, before I’d actually gone to school to learn a thing or two about software development. There was some BASIC, some Pascal, and looking at it now, it’s all pretty ugly.

So let’s get real. Bad programmers write bad code. Good programmers write good code. RAD lets bad programmers write bad code faster. RAD does NOT cause good programmers to suddenly start writing bad code. RAD tools can make a good programmer more productive, because they speed up the coding process without compromising the level of quality that a good programmer is going to achieve.

Petzold’s essay meanders a bit, but ultimately cuts a little deeper than “R.A.D. is B.A.D.”:

Life without Visual Studio is unimaginable, and yet, no less than PowerPoint, Visual Studio causes us to do our jobs in various predefined ways, and I, for one, would be much happier if Visual Studio did much less than what it does. Certain features in Visual Studio are supposed to make us more productive, and yet for me, they seem to denigrate and degrade the programming experience.

Petzold argues that the cognitive model that Visual Studio forces on the developer is fundamentally flawed. This is essentially the same argument presented in Edward Tufte’s 2003 essay, The Cognitive Style of PowerPoint.* Petzold goes on to illustrate with intellisense, which he has a love/hate relationship with:

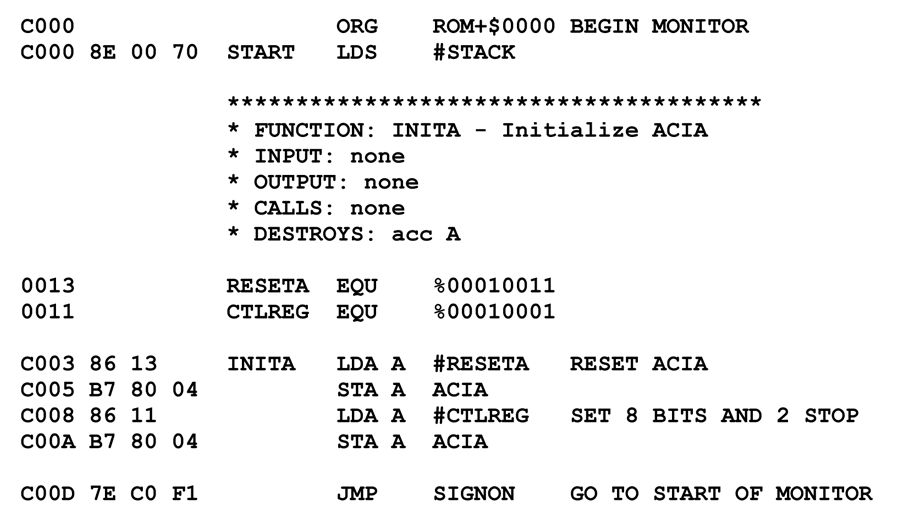

But the implication here is staggering. To get IntelliSense to work right, not only must you code in a bottom-up structure, but within each method or property, you must also write you code linearly from beginning to end – just as if you were using that old DOS line editor, EDLIN. You must define all variables before you use them. No more skipping around in your code. It’s not that IntelliSense is teaching us to program like a machine; it’s just that IntelliSense would be much happier if we did.

And then there’s the issue of code generation:

Even if Visual Studio generated immaculate code, there would still be a problem. As Visual Studio is generating code, it is also erecting walls between that code and the programmer. Visual Studio is implying that this is the only way you can write a modern Windows or web program because there are certain aspects of modern programming that only it knows about. And Visual Studio adds to this impression by including boilerplate code that contains stuff that has never really been adequately discussed in the tutorials or documentation that Microsoft provides.

It becomes imperative to me, as a teacher of Windows Forms programming and Avalon programming, to deliberately go in the opposite direction. I feel I need to demystify what Visual Studio is doing and demonstrate how you can develop these applications by writing your own code, and even, if you want, compiling this code on the command line totally outside of Visual Studio.

In my Windows Forms books, I tell the reader not to choose Windows Application when starting a new Windows Forms project, but to choose the Empty Project option instead. The Empty Project doesn’t create anything except a project file. All references and all code has to be explicitly added.

Am I performing a service by showing programmers how to write code in a way that is diametrically opposed to the features built into the tool that they’re using? I don’t know. Maybe this is wrong, but I can’t see any alternative.

In other words, a developer weaned on the Visual Studio .NET IDE is powerless outside that environment. Working in the Visual Studio IDE becomes synonymous with the very act of programming. And that’s the thing Petzold is most afraid of:

[to solve a New Scientist math puzzle] I decided to use plain old ANSI C, and to edit the source code in Notepad – which has no IntelliSense and no sense of any other kind – and to compile on the command line using both the Microsoft C compiler and the Gnu C compiler.

What’s appealing about this project is that I don’t have to look anything up. I’ve been coding in C for 20 years. It was my favorite language before C# came along. This stuff is just pure algorithmic coding with simple text output. It’s all content. Even after this preliminary process, there’s still coding to do, but there’s no APIs, there’s no classes, there’s no properties, there’s no forms, there’s no controls, there’s no event handlers, and there’s definitely no Visual Studio.

It’s just me and the code, and for awhile, I feel like a real programmer again.

Using Notepad to code may be an instructive exercise in minimalism for students, but no professional programmer can afford to build software this way. If anything, I think the future lies in even tighter coupling of the language and the IDE. I can even envision a day where it isn’t possible to compile a program outside the IDE – and that’s probably heresy to Petzold.

But it’s also the future.

*Tufte’s essay is also available in parody powerpoint form.