Programmers and Chefs

From an audio interview with Ron Jeffries:

The reason the kitchen is a mess is not because the kitchen is poorly designed, it’s because we didn’t do the dishes after every meal.

Michael Feathers recently wrote an eerily similar entry about the professional chef’s concept of working clean:

One other thing that I liked about the Pastry Chef’s competition was the way that the chefs were judged. There was more to it than just the final judging. All during the preparation, judges walked from station to station with clipboards, making little notes. One of the criteria that they used was working clean. Imagine that... working clean... The judges were watching to make sure that the chefs rubbed clean every bowl and utensil immediately after use. If they didn’t, well, they were marked off.

Micah Martin left a great comment that illustrates how integral “working clean” is to professionals in the restaurant industry:

In my college years I was a chef/line cook at a few restaurants. Indeed working clean is a common theme in the kitchen. The term I heard over and over was “Clean as you go!” “Clean as you go!” wasn’t so much a suggestion, but rather a law. Those cooks who didn’t constantly clean would wind up in trouble. Their workspace would become so messy within a matter of an hour or two that the quality of food rapidly diminished. This problem would progress until the other cooks were forced to step in and clean up. This had a negative impact on the entire kitchen and Nobody was happy it happened. Interestingly, line cooks, even without college degrees, were extremely efficient as self-management. Those cook who didn’t work clean, were taunted, teased, and pushed around until they cleaned up, or quit.

For software developers, working clean means constant refactoring. If you don’t stop occasionally – frequently, actually – to revisit and clean up the code you’ve already written, you’re bound to end up with a big, sloppy ball of code. If you forget to regularly clean up behind yourself, things get smelly. Working clean means following your nose and addressing those nagging issues before they become catastrophic.

In addition to working clean, cooks also spend a lot of time thinking about mise en place, how their cooking stations are arranged for optimal work. Michael Feathers explains:

There’s an section in [the book Kitchen Confidential] where he talks about what cooks do late at night after the customers have gone home. They generally do what many people after work, they go out for beers and sit around talking about work, but what do they talk about really? Tony says that the subject that always comes up is something called mise en place. Mise en place is a blanket term for how you set up your station.

Is your tub of butter at the eleven o’clock position or at the one o’clock? Do you have two paring knives, and do you keep them next to your cutting board or next to your garnish bin? When you spend the night churning out meals, these decisions make a difference. Everyone has their favorite theory about the proper miz. Tony says that many cooks get downright mystical about it. According Tony, you’d better run if you are caught messing with another cook’s miz. Sharp knives have multiple uses, apparently.

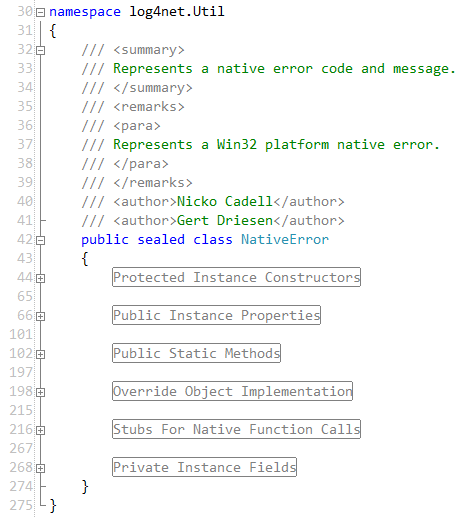

The concept of mise en place should be familiar to software developers. It’s why every member of the team has their development system set up identically. It’s why we use a common set of development tools. It’s why we take advantage of existing frameworks like nUnit and Log4Net instead of writing our own.

Good programmers should be borderline obsessive about their “miz.” Our craft changes too rapidly for us to ever be completely satisfied with the way we’re working today. There’s always something better on the horizon.