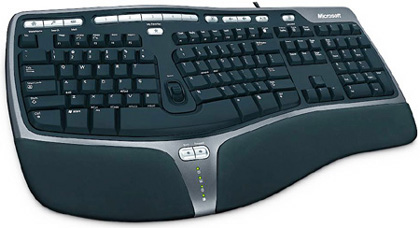

keyboard

Have Keyboard, Will Program

My beloved Microsoft Natural Keyboard 4000 has succumbed to the relentless pounding of my fingers. A moment of silence, please. OK, it still works, technically, but certain keys have become... unreliable. In particular, the semicolon key is now infuriatingly difficult to use. I don’t know if this is God’