programming languages

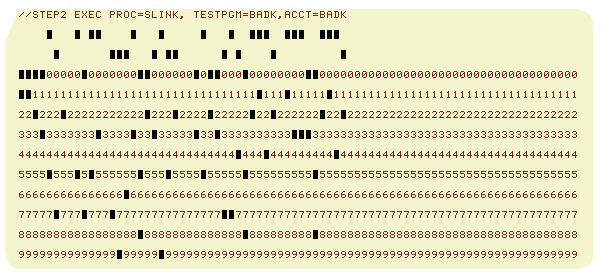

The Paper Data Storage Option

As programmers, we regularly work with text encodings. But there’s another sort of encoding at work here, one we process so often and so rapidly that it’s invisible to us, and we forget about it. I’m talking about visual encoding – translating the visual glyphs of the alphabet