Scott Stanfield forwarded me a link to Roger Sessions' A Better Path to Enterprise Architecture yesterday. Even though it's got the snake-oil word "Enterprise" in the title, the article is surprisingly good.

I particularly liked the unusual analogy Roger chose to illustrate the difference between iterative and recursive approaches to software development. It starts with Air Force Colonel John Boyd researching a peculiar anomaly in the performance of 1950's era jet fighters:

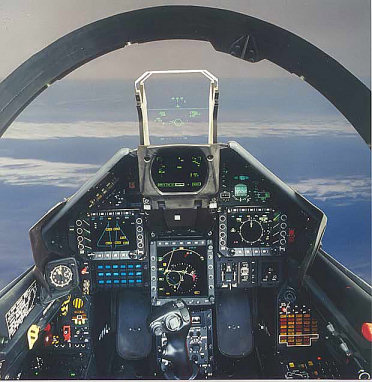

Colonel John Boyd was interested not just in any dogfights, but specifically in dogfights between MiG-15s and F-86s. As an ex-pilot and accomplished aircraft designer, Boyd knew both planes very well. He knew the MiG-15 was a better aircraft than the F-86. The MiG-15 could climb faster than the F-86. The MiG-15 could turn faster than the F-86. The MiG-15 had better distance visibility.

The F-86 had two points in its favor. First, it had better side visibility. While the MiG-15 pilot could see further in front, the F-86 pilot could see slightly more on the sides. Second, the F-86 had a hydraulic flight control. The MiG-15 had a manual flight control.

The standing assumption on the part of airline designers was that maneuverability was the key component of winning dogfights. Clearly, the MiG-15, with its faster turning and climbing ability, could outmaneuver the F-86.

There was just one problem with all this. Even though the MiG-15 was considered a superior aircraft by aircraft designers, the F-86 was favored by pilots. The reason it was favored was simple: in one-on-one dogfights with MiG-15s, the F-86 won nine times out of ten.

How can an inferior aircraft consistently win over a superior aircraft? Boyd, who was himself one of the best dogfighters in history, had a theory:

Boyd decided that the primary determinant to winning dogfights was not observing, orienting, planning, or acting better. The primary determinant to winning dogfights was observing, orienting, planning, and acting faster. In other words, how quickly one could iterate. Speed of iteration, Boyd suggested, beats quality of iteration.

The next question Boyd asked is this: why would the F-86 iterate faster? The reason, he concluded, was something that nobody had thought was particularly important. It was the fact that the F-86 had a hydraulic flight stick whereas the MiG-15 had a manual flight stick.

Without hydraulics, it took slightly more physical energy to move the MiG-15 flight stick than it did the F-85 flight stick. Even though the MiG-15 would turn faster (or climb higher) once the stick was moved, the amount of energy it took to move the stick was greater for the MiG-15 pilot.

With each iteration, the MiG-15 pilot grew a little more fatigued than the F-86 pilot. And as he gets more fatigued, it took just a little bit longer to complete his OOPA loop. The MiG-15 pilot didn't lose because he got outfought. He lost because he got out-OOPAed.

This leads to Boyd's Law of Iteration: speed of iteration beats quality of iteration.

You'll find this same theme echoed throughout every discipline of modern software engineering:

- Unit tests should be small and fast, so you can run them with every build.

- Usability tests work best if you make small changes every two weeks and quickly discard what isn't working.

- Most agile approaches recommend iterations no longer than 4 weeks.

- Software testing is about failing early and often.

- Functional specifications are best when they're concise and evolving.

When in doubt, iterate faster.

Discussion