software development concepts

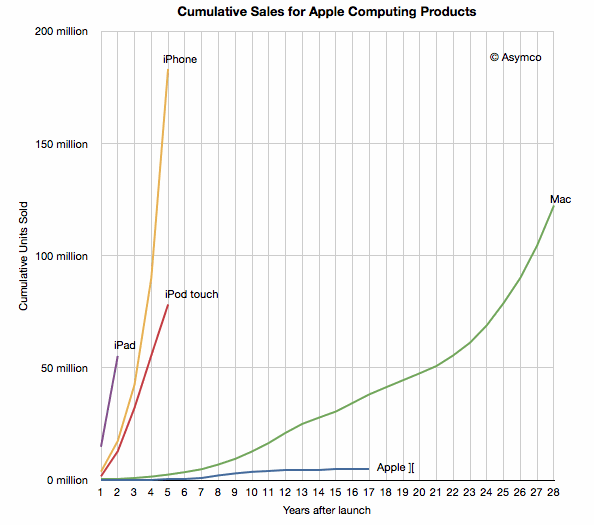

Welcome to the Post PC Era

What was Microsoft’s original mission? In 1975, Gates and Allen form a partnership called Microsoft. Like most startups, Microsoft begins small, but has a huge vision – a computer on every desktop and in every home. The existential crisis facing Microsoft is that they achieved their mission years ago, at