Computer Crime, Then and Now

I’ve already documented my brief, youthful dalliance with the illegal side of computing as it existed in the late 1980s. But was it crime? Was I truly a criminal? I don’t think so. To be perfectly blunt, I wasn’t talented enough to be any kind of threat. I’m still not.

There are two classic books describing hackers active in the 1980s who did have incredible talent. Talents that made them dangerous enough to be considered criminal threats.

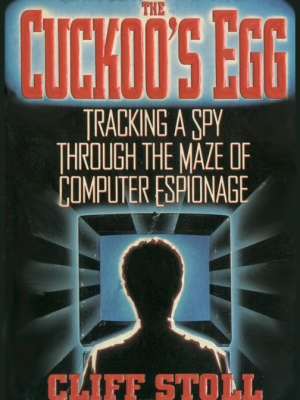

The Cuckoo’s Egg: Tracking a Spy Through the Maze of Computer Espionage

Ghost in the Wires: My Adventures as the World’s Most Wanted Hacker

Cuckoo is arguably the first case of hacking that was a clearly malicious crime circa 1986, and certainly the first known case of computer hacking as international espionage. I read this when it was originally published in 1989, and it’s still a gripping investigative story. Cliff Stoll is a visionary writer who saw how trust in computers and the emerging Internet could be vulnerable to real, actual, honest-to-God criminals.

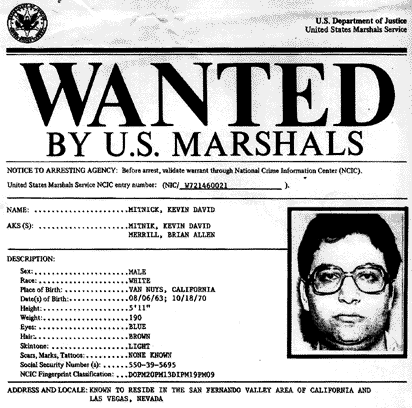

I’m not sure Kevin Mitnick did anything all that illegal, but there’s no denying that he was the world’s first high profile computer criminal.

By 1994 he made the FBI’s 10 Most Wanted list, and there were front page New York Times articles about his pursuit. If there was ever a moment that computer crime and “hacking” entered the public consciousness as an ongoing concern, this was it.

The whole story is told in minute detail by Kevin himself in Ghost in the Wires. There was a sanitized version of Kevin’s story presented in Wizzywig comix but this is the original directly from the source, and it’s well worth reading. I could barely put it down. Kevin has been fully reformed for many years now; he wrote several books documenting his techniques and now consults with companies to help improve their computer security.

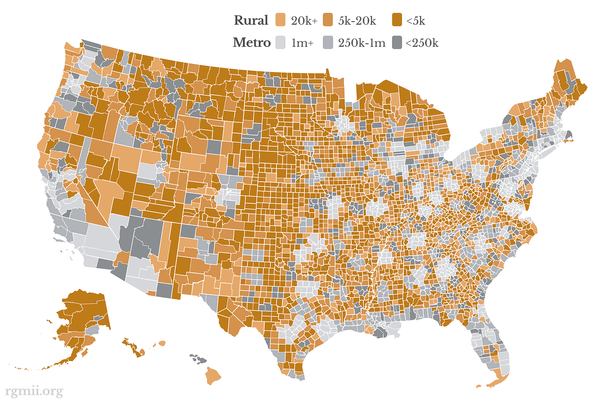

These two books cover the genesis of all computer crime as we know it. Of course it’s a much bigger problem now than it was in 1985, if for no other reason than there are far more computers far more interconnected with each other today than anyone could have possibly imagined in those early days. But what’s really surprising is how little has changed in the techniques of computer crime since 1985.

The best primer of modern – and by that I mean year 2000 and later – computer crime is Kingpin: How One Hacker Took Over the Billion-Dollar Cybercrime Underground. Modern computer crime is more like the classic sort of crime you’ve seen in black and white movies: it’s mostly about stealing large sums of money. But instead of busting it out of bank vaults Bonnie and Clyde style, it’s now done electronically, mostly through ATM and credit card exploits.

Written by Kevin Poulson, another famous reformed hacker, Kingpin is also a compelling read. I’ve read it twice now. The passage I found most revealing is this one, written after the protagonist’s release from prison in 2002:

One of Max’s former clients in Silicon Valley tried to help by giving Max a $5,000 contract to perform a penetration test on the company’s network. The company liked Max and didn’t really care if he produced a report, but the hacker took the gig seriously. He bashed at the company’s firewalls for months, expecting one of the easy victories to which he’d grown accustomed as a white hat. But he was in for a surprise. The state of corporate security had improved while he was in the joint. He couldn’t make a dent in the network of his only client. His 100 percent success record was cracking.

Max pushed harder, only becoming more frustrated over his powerlessness. Finally, he tried something new. Instead of looking for vulnerabilities in the company’s hardened servers, he targeted some of the employees individually.

These “client side” attacks are what most people experience of hackers – a spam e-mail arrives in your in-box, with a link to what purports to be an electronic greeting card or a funny picture. The download is actually an executable program, and if you ignore the warning message

All true; no hacker today would bother with frontal assaults. The chance of success is miniscule. Instead, they target the soft, creamy underbelly of all companies: the users inside. Max, the hacker described in Kingpin, bragged “I’ve been confident of my 100 percent [success] rate ever since.” This is the new face of hacking. Or is it?

One of the most striking things about Ghost In The Wires is not how skilled a computer hacker Kevin Mitnick is (although he is undeniably great), but how devastatingly effective he is at tricking people into revealing critical information in casual conversations. Over and over again, in hundreds of subtle and clever ways. Whether it’s 1985 or 2005, the amount of military-grade security you have on your computer systems matters not at all when someone using those computers clicks on the dancing bunny. Social engineering is the most reliable and evergreen hacking technique ever devised. It will outlive us all.

For a 2012 era example, consider the story of Mat Honan. It is not unique.

At 4:50 PM, someone got into my iCloud account, reset the password and sent the confirmation message about the reset to the trash. My password was a 7 digit alphanumeric that I didn’t use elsewhere. When I set it up, years and years ago, that seemed pretty secure at the time. But it’s not. Especially given that I’ve been using it for, well, years and years. My guess is they used brute force to get the password and then reset it to do the damage to my devices.

I heard about this on Twitter when the story was originally developing, and my initial reaction was skepticism that anyone had bothered to brute force anything at all, since brute forcing is for dummies. Guess what it turned out to be. Go ahead, guess!

Did you by any chance guess social engineering – of the account recovery process? Bingo.

After coming across my [Twitter] account, the hackers did some background research. My Twitter account linked to my personal website, where they found my Gmail address. Guessing that this was also the e-mail address I used for Twitter, Phobia went to Google’s account recovery page. He didn’t even have to actually attempt a recovery. This was just a recon mission.

Because I didn’t have Google’s two-factor authentication turned on, when Phobia entered my Gmail address, he could view the alternate e-mail I had set up for account recovery. Google partially obscures that information, starring out many characters, but there were enough characters available, m••••[email protected]. Jackpot.

Since he already had the e-mail, all he needed was my billing address and the last four digits of my credit card number to have Apple’s tech support issue him the keys to my account.

So how did he get this vital information? He began with the easy one. He got the billing address by doing a who is search on my personal web domain. If someone doesn’t have a domain, you can also look up his or her information on Spokeo, WhitePages, and PeopleSmart.

Getting a credit card number is tricker, but it also relies on taking advantage of a company’s back-end systems… First you call Amazon and tell them you are the account holder, and want to add a credit card number to the account. All you need is the name on the account, an associated e-mail address, and the billing address. Amazon then allows you to input a new credit card. (Wired used a bogus credit card number from a website that generates fake card numbers that conform with the industry’s published self-check algorithm.) Then you hang up.

Next you call back, and tell Amazon that you’ve lost access to your account. Upon providing a name, billing address, and the new credit card number you gave the company on the prior call, Amazon will allow you to add a new e-mail address to the account. From here, you go to the Amazon website, and send a password reset to the new e-mail account. This allows you to see all the credit cards on file for the account – not the complete numbers, just the last four digits. But, as we know, Apple only needs those last four digits.

Phobia, the hacker Mat Honan documents, was a minor who did this for laughs. One of his friends is a 15 year old hacker who goes by the name of Cosmo; he’s the one who discovered the Amazon credit card technique described above. And what are teenage hackers up to these days?

Xbox gamers know each other by their gamertags. And among young gamers it’s a lot cooler to have a simple gamertag like “Fred” than, say, “Fred1988Ohio.” Before Microsoft beefed up its security, getting a password-reset form on Windows Live (and thus hijacking a gamer tag) required only the name on the account and the last four digits and expiration date of the credit card on file. Derek discovered that the person who owned the “Cosmo” gamer tag also had a Netflix account. And that’s how he became Cosmo.

“I called Netflix and it was so easy,” he chuckles. “They said, ‘What’s your name?’ and I said, ‘Todd [Redacted],’ gave them his e-mail, and they said, ‘Alright your password is 12345,’ and I was signed in. I saw the last four digits of his credit card. That’s when I filled out the Windows Live password-reset form, which just required the first name and last name of the credit card holder, the last four digits, and the expiration date.”

This method still works. When Wired called Netflix, all we had to provide was the name and e-mail address on the account, and we were given the same password reset.

The techniques are eerily similar. The only difference between Cosmo and Kevin Mitnick is that they were born in different decades. Computer crime is a whole new world now, but the techniques used today are almost identical to those used in the 1980s. If you want to engage in computer crime, don’t waste your time developing ninja level hacking skills, because computers are not the weak point.

People are.