The Great Newline Schism

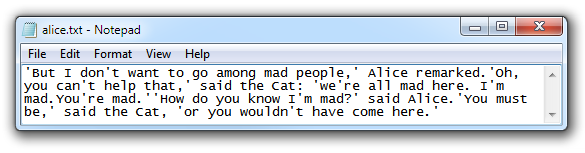

Have you ever opened a simple little ASCII text file to see it inexplicably displayed as onegiantunbrokenline?

Opening the file in a different, smarter text editor results in the file displayed properly in multiple paragraphs.

The answer to this puzzle lies in our old friend, invisible characters that we can’t see but that are totally not out to get us. Well, except when they are.

The invisible problem characters in this case are newlines.

Did you ever wonder what was at the end of your lines? As a programmer, I knew there were end of line characters, but I honestly never thought much about them. They just... worked. But newlines aren’t a universally accepted standard; they are different depending who you ask, and what platform they happen to be computing on:

| DOS / Windows | CR LF | rn | 0x0D 0x0A |

| Mac (early) | CR | r | 0x0D |

| Unix | LF | n | 0x0A |

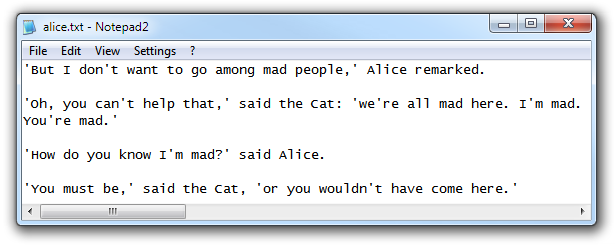

The Carriage Return (CR) and Line Feed (LF) terms derive from manual typewriters, and old printers based on typewriter-like mechanisms (typically referred to as “Daisywheel” printers.)

On a typewriter, pressing Line Feed causes the carriage roller to push up one line – without changing the position of the carriage itself – while the Carriage Return lever slides the carriage back to the beginning of the line. In all honesty, I’m not quite old enough to have used electric typewriters, so I have a dim recollection, at best, of the entire process. The distinction between CR and LF does seem kind of pointless – why would you want to move to the beginning of a line without also advancing to the next line? This is another analog artifact, as Wikipedia explains:

On printers, teletypes, and computer terminals that were not capable of displaying graphics, the carriage return was used without moving to the next line to allow characters to be placed on top of existing characters to produce character graphics, underlines, and crossed out text.

So far we’ve got:

- Confusing terms based on archaic hardware that is no longer in use, and is confounding to new users who have no point of reference for said terms;

- Completely arbitrary platform “standards” for what is exactly the same function.

Pretty much business as usual in computing. If you’re curious, as I was, about the historical basis for these decisions, Wikipedia delivers all the newline trivia you could possibly want, and more:

The sequenceCR+LFwas in common use on many early computer systems that had adopted teletype machines, typically an ASR33, as a console device, because this sequence was required to position those printers at the start of a new line. On these systems, text was often routinely composed to be compatible with these printers, since the concept of device drivers hiding such hardware details from the application was not yet well developed; applications had to talk directly to the teletype machine and follow its conventions. The separation of the two functions concealed the fact that the print head could not return from the far right to the beginning of the next line in one-character time. That is why the sequence was always sent with the CR first. In fact, it was often necessary to send extra characters (extraneous CRs or NULs, which are ignored) to give the print head time to move to the left margin. Even after teletypes were replaced by computer terminals with higher baud rates, many operating systems still supported automatic sending of these fill characters, for compatibility with cheaper terminals that required multiple character times to scroll the display.

CP/M’s use ofCR+LFmade sense for using computer terminals via serial lines. MS-DOS adopted CP/M’sCR+LF, and this convention was inherited by Windows.

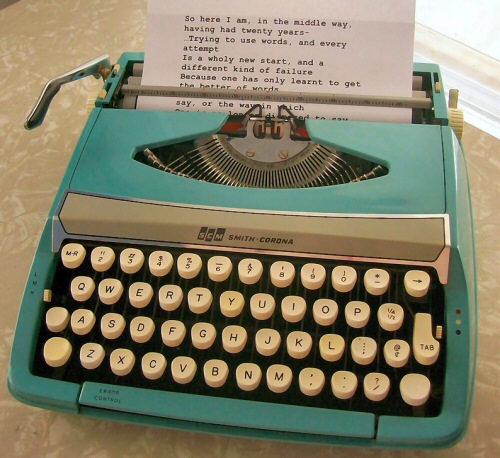

This exciting difference in how newlines work means you can expect to see one of three (or more, as we’ll find out later) newline characters in those “simple” ASCII text files.

If you’re fortunate, you’ll pick a fairly intelligent editor that can detect and properly display the line endings of whatever text files you open. If you’re less fortunate, you’ll see onegiantunbrokenline, or a bunch of extra ^M characters in the file.

Even worse, it’s possible to mix all three of these line endings in the same file. Innocently copy and paste a comment or code snippet from a file with a different set of line endings, then save it. Bam, you’ve got a file with multiple line endings. That you can’t see. I’ve accidentally done it myself. (Note that this depends on your choice of text editor; some will auto-normalize line endings to match the current file’s settings upon paste.)

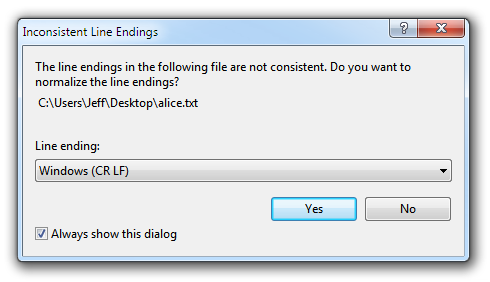

This is complicated by the fact that some editors, even editors that should know better, like Visual Studio, have no mode that shows end of line markers. That’s why, when attempting to open a file that has multiple line endings, Visual Studio will politely ask you if it can normalize the file to one set of line endings.

This Visual Studio dialog presents the following five (!) possible set of line endings for the file:

- Windows (CR LF)

- Macintosh (CR)

- Unix (LF)

- Unicode Line Separator (LS)

- Unicode Paragraph Separator (PS)

The last two are new to me. I’m not sure under what circumstances you would want those Unicode newline markers.

Even if you rule out unicode and stick to old-school ASCII, like most Facebook relationships... it’s complicated. I find it fascinating that the mundane ASCII newline has so much ancient computing lore behind it, and that it still regularly bites us in unexpected places.

If you work with text files in any capacity – and what programmer doesn’t – you should know that not all newlines are created equally. The Great Newline Schism is something you need to be aware of. Make sure your tools can show you not just those pesky invisible white space characters, but line endings as well.