Respecting Abstraction

In a recent post, Scott Koon proposes that to be a really good .NET programmer, you also need to be a really good C++ programmer:

If you’ve spent all your life working in a GC’ed language, why would you ever need to know how memory management works, let alone virtual memory? Jon also says it doesn’t teach you to work with a framework. What’s the STL? What about MFC? ATL? Carbon? All of those things use C++ as their base language. Notice I didn’t say to take a C/C++ course at a university as I’m not convinced that a CS course will teach you everything you need to know in the real world. I said to learn C/C++ first because if you understand HOW things work, you’ll have a better idea of how things DON’T work. How can you identify a memory leak in your managed application if you don’t know how memory leaks come about or what a memory leak is?

The problem I have with this position is that it breaks abstraction. The .NET framework abstracts away the details of pointers and memory management by design, to make development easier. But it’s also a stretch to say that .NET developers have no idea what memory leaks are – in the world of managed code, memory management is an optimization, not a requirement. It’s an important distinction. You should only care when it makes sense to do so, whereas in C++ you are forced to worry about the minutia of detailed memory management even for the most trivial of applications. And if you get it wrong, either your app crashes, or you’re open to buffer overrun exploits.

You may also be familiar with Joel’s article on the negative effects of leaky abstractions. Bram has a compelling response:

Joel Spolsky says: “All non-trivial abstractions, to some degree, are leaky.”

This is overly dogmatic – for example, bignum classes are exactly the same regardless of the native integer multiplication. Ignoring that, this statement is essentially true, but rather inane and missing the point. Without abstractions, all our code would be completely interdependent and unmaintainable, and abstractions do a remarkable job of cleaning that up. It is a testament to the power of abstraction and how much we take it for granted that such a statement can be made at all, as if we always expected to be able to write large pieces of software in a maintainable manner.

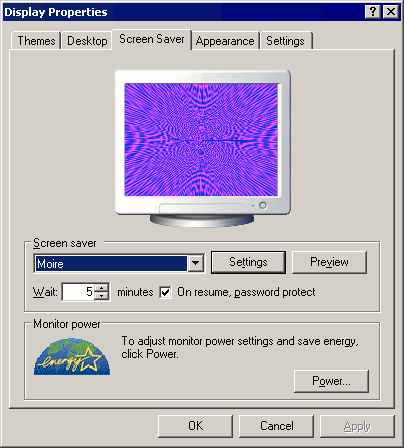

It’s amazing how far down the rabbit hole you can go following the many abstractions that we routinely rely on today. Eric Sink documents the 46 layers of abstraction that his product relies on. And Eric stops before we get to the real iron; Charles Petzold’s excellent book, Code: The Hidden Language of Computer Hardware and Software goes even deeper. In other words, when Joel says:

Today, to work on CityDesk, I need to know Visual Basic, COM, ATL, C++, InnoSetup, Internet Explorer internals, regular expressions, DOM, HTML, CSS, and XML. All high level tools compared to the old K&R stuff, but I still have to know the K&R stuff or I’m toast.

What he’s really saying is without these abstractions, we’d all be toast. While no abstraction is perfect – you may need to dip your toes into layers below the Framework from time to time – arguing that you must have detailed knowledge of the layer under the abstraction to be competent is counterproductive. While I don’t deny that knowledge of the layers is critical for troubleshooting, we should respect the abstractions and spend most of our efforts fixing the leaks instead of bypassing them.