c#

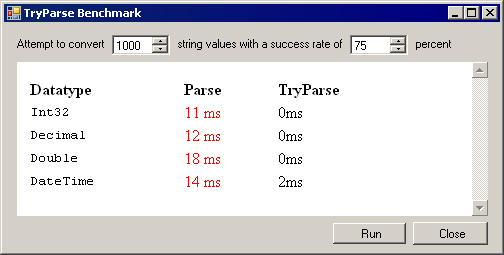

TryParse and the Exception Tax

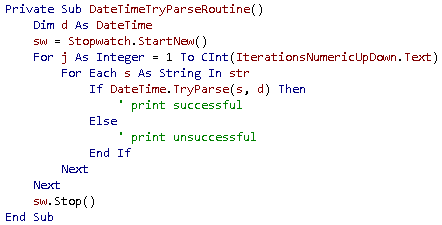

In .NET 1.1, TryParse is only available for the Double datatype. Version 2.0 of the framework extends TryParse to all the basic datatypes. Why do we care? Performance. Parse throws an exception if the conversion from a string to the specified datatype fails, whereas TryParse explicitly avoids throwing