registry

Stupid Registry Tricks

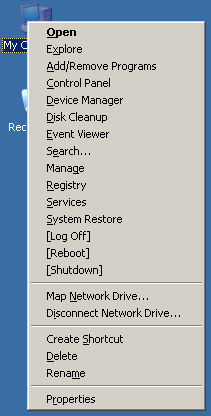

Scott Hanselman’s Power User Windows Registry Tweaks has some excellent registry editing tweaks. I’ve spent the last few hours poring over those registry scripts, enhancing and combining them with some favorites of my own. Here are the results: * Open Command Window Here Adds a right-click menu to all