security

Why Do Login Dialogs Have a “User” Field?

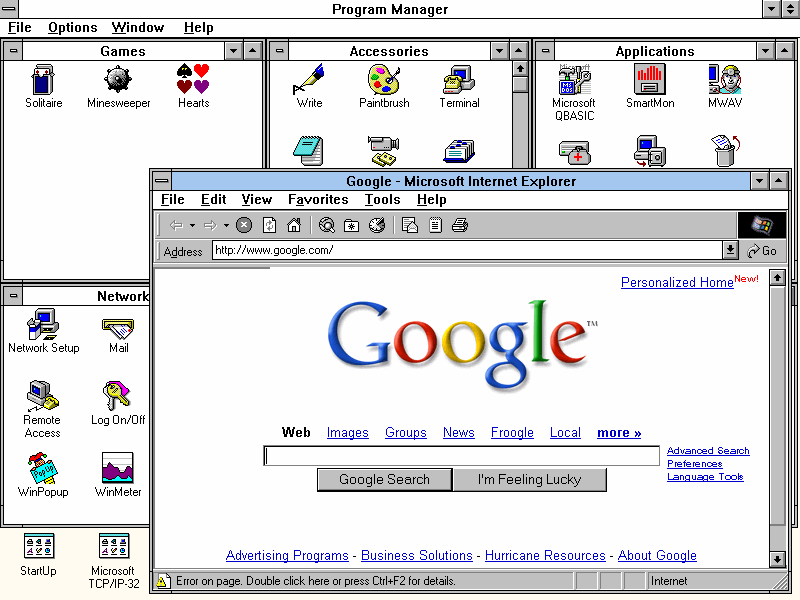

In The Humane Interface, the late Jef Raskin asks an intriguing question: why do login dialogs have a “User” field? Shouldn’t login dialogs look more like this? And you know what? He’s right. Your password alone should be enough information for the computer to know who you are.