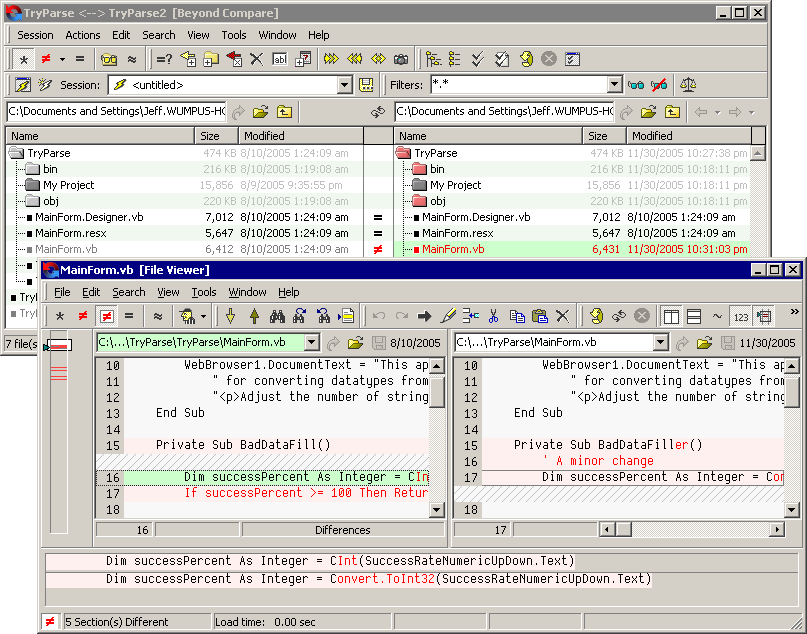

image compression

Screenshots: JPEG vs. GIF (and PNG)

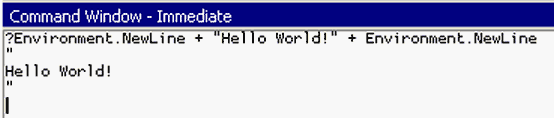

It constantly amazes me how many times I encounter pages where screenshots are inappropriately stored as JPEGs. Not to single Mike Gunderloy out, but there’s yet another example in his recent article on configuring an ASP.NET 2.0 website: That is just nasty. As in, Miss Jackson if