aws

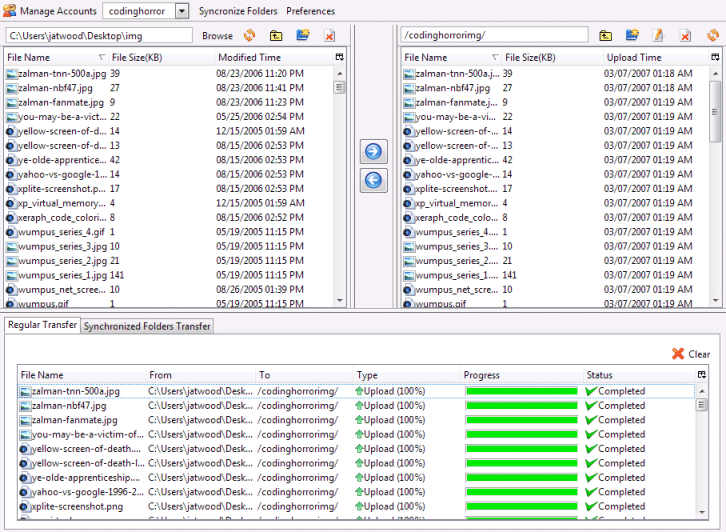

Using Amazon S3 as an Image Hosting Service

In Reducing Your Website’s Bandwidth Usage, I concluded that my best outsourced image hosting option was Amazon’s S3 or Simple Storage Service. S3 is a popular choice for startups. For example, SmugMug uses S3 as their primary data storage source. There have been a few minor S3-related bumps