Listen to Your Community, But Don’t Let Them Tell You What to Do

You know how interviewers love asking about your greatest weakness, or the biggest mistake you’ve ever made? These questions may sound formulaic, maybe even borderline cliché, but be careful when you answer: they are more important than they seem.

So when people ask me what our biggest mistake was in building Stack Overflow I’m glad I don’t have to fudge around with platitudes. I can honestly and openly point to a huge, honking, ridiculously dumb mistake I made from the very first day of development on Stack Overflow – and, worse, a mistake I stubbornly clung to for a solid nine month period after that over the continued protestations of the community. I even went so far as to write a whole blog post decrying its very existence.

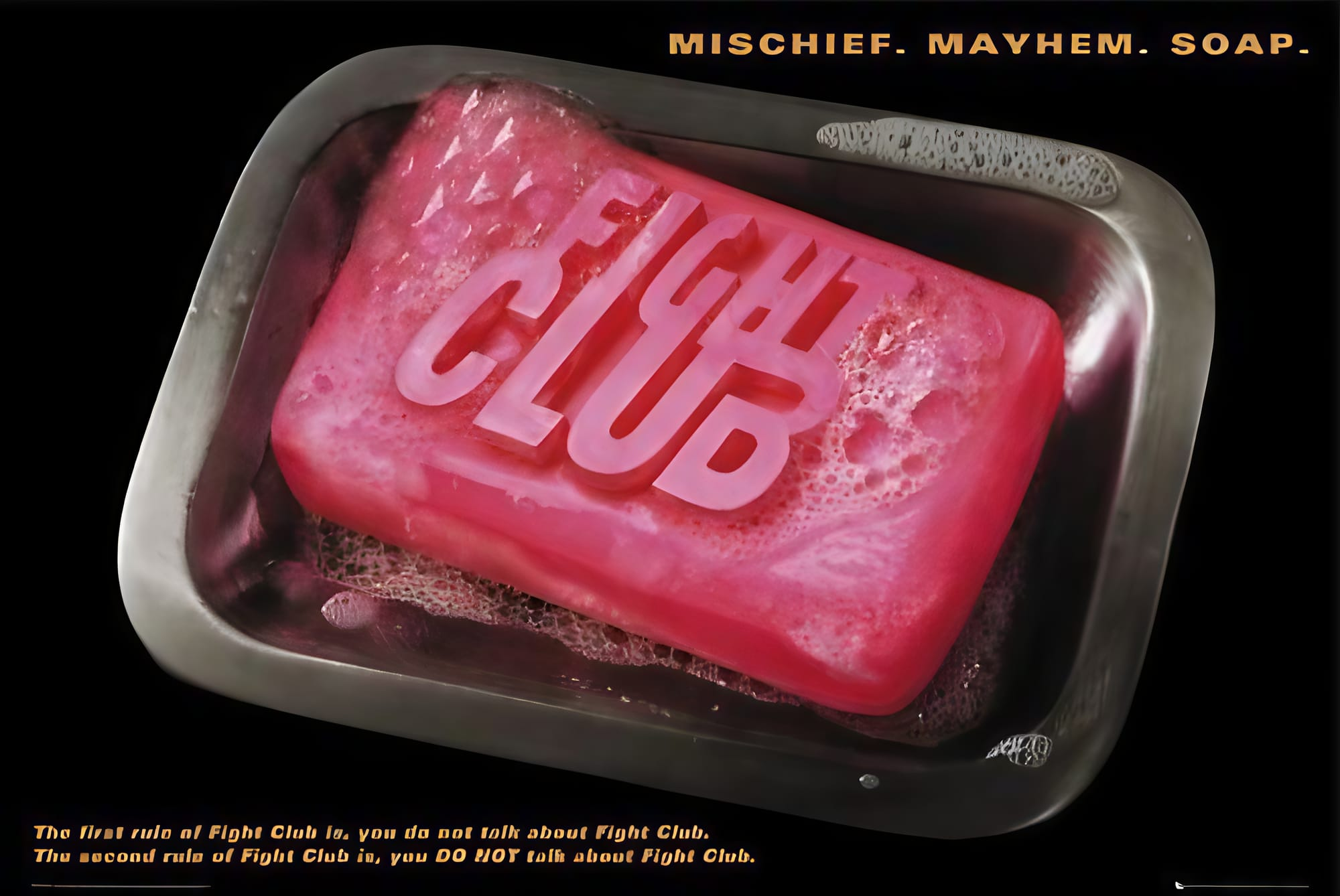

For the longest time, I had an awfully Fight Club-esque way of looking at this: the first rule of Stack Overflow was that you didn’t discuss Stack Overflow! After all, we were there to learn about programming with our peers, not learn about a stupid website. Right?

I didn’t see the need for a meta.

Meta is, of course, the place where you go to discuss the place. Take a moment and think about what that means. Meta is for people who care so deeply about their community that they’re willing to go one step further, to come together and spend even more of their time deciding how to maintain and govern it. So, in a nutshell, I was telling the people who loved Stack Overflow the most of all to basically… f**k off and go away.

As I said, not my finest hour.

In my defense, I did eventually figure this out, thanks to the continued prodding of the community. Although we’d used an external meta site since beta, we eventually launched our very own meta.stackoverflow in June 2009, ten months after public beta. And we fixed this very definitively with Stack Exchange. Every Stack Exchange site we launch has a meta from day one. We now know that meta participation is the source of all meaningful leadership and governance in a community, so it is cultivated and monitored closely.

I also paid penance for my sins by becoming the top user of our own meta. I’ve spent the last 2 years and 7 months totally immersed in the morass of bugs, feature requests, discussions, and support that is our meta. As you can see in my profile, I’ve visited meta 901 unique days in that time frame, which is disturbingly close to every day. I consider my meta participation stats a badge of honor, but more than that, it’s my job to help build this thing alongside you. We explicitly do everything in public on Stack Exchange – it’s very intentionally the opposite of Ivory Tower Development.

Along the way I’ve learned a few lessons about building software with your community, and handling community feedback.

1. 90% of all community feedback is crap.

Let’s get this out of the way immediately. Sturgeon’s Law can’t be denied by any man, woman, child… or community, for that matter. Meta community, I love you to death, so let’s be honest with each other: most of the feedback and feature requests you give us are just not, uh, er… actionable, for a zillion different reasons.

But take heart: this means 10% of the community feedback you’ll get is awesome! I guarantee you’ll find ten posts that are pure gold, that have the potential to make the site clearly better for everyone… provided you have the intestinal fortitude to look at a hundred posts to get there. Be prepared to spend a lot of time, and I mean a whole freaking lot of time, mining through community feedback to extract those rare gems. I believe every community has users savvy enough to produce them in some quantity, and they’re often startlingly wonderful.

2. Don’t get sweet talked into building a truck.

You should immediately triage the feedback and feature requests you get into two broad buckets:

We need power windows in this car!

or

We need a truck bed in this car!

The former is, of course, a reasonable thing to request adding to a car, while the latter is a request to change the fundamental nature of the vehicle. The malleable form of software makes it all too tempting to bolt that truck bed on to our car. Why not? Users keep asking for it, and trucks sure are convenient, right?\

Don’t fall into this trap. Stay on mission. That car-truck hybrid is awfully tempting to a lot of folks, but then you end up with a Subaru Brat. Unless you really want to build a truck after all, the users asking for truck features need to be gently directed to their nearest truck dealership, because they’re in the wrong place.

3. Be honest about what you won’t do.

It always depressed me to see bug trackers and feedback forums with thousands of items languishing there in no man’s land with no status at all. That’s a sign of a neglected community, and worse, a dishonest relationship with the community. It is sadly all too typical. Don’t do this!

I’m not saying you should tell your community that their feedback sucks, even when it frequently does. That’d be mean. But don’t be shy about politely declining requests when you feel they don’t make sense, or if you can’t see any way they could be reasonably implemented. (You should always reserve the right to change your mind in the future, of course.) Sure, it hurts to be rejected – but it hurts far more to be ignored. I believe very, very strongly that if you’re honest with your community, they will ultimately respect you more for that.

All relationships are predicated on honesty. If you’re not willing to be honest with your community, how can you possibly expect them to respect you… or continue the relationship?

4. Listen to your community, but don’t let them tell you what to do.

It’s tempting to take meta community requests as a wholesale template for development of your software or website. The point of a meta is to listen to your community, and act on that feedback, right? On the contrary, acting too directly on community feedback is incredibly dangerous, and the reason many of these community initiatives fail when taken too literally. I’ll let Tom Preston-Werner, the co-founder of GitHub, explain:

Consider a feature request such as “GitHub should let me FTP up a documentation site for my project.” What this customer is really trying to say is “I want a simple way to publish content related to my project,” but they’re used to what’s already out there, and so they pose the request in terms that are familiar to them. We could have implemented some horrible FTP based solution as requested, but we looked deeper into the underlying question and now we allow you to publish content by simply pushing a Git repository to your account. This meets requirements of both functionality and elegance.

Community feedback is great, but it should never be used as a crutch, a substitute for thinking deeply about what you’re building and why. Always try to identify what the underlying needs are, and come up with a sensible roadmap.

5. Be there for your community.

Half of community relationships isn’t doing what the community thinks they want at any given time, but simply being there to listen and respond to the community. When the co-founder of Stack Exchange responds to your meta post – even if it wasn’t exactly what you may have wanted to hear – I hope it speaks volumes about how committed we are to really, truly building this thing alongside our community.

Regardless of whether money is changing hands or not, you should love discovering some small gem of a community request or bugfix on meta that makes your site or product better, and swooping in to make it so. That’s a virtuous public feedback loop: it says you matter and we care and everything just keeps on getting better all in one delightful gesture.

And isn’t that what it’s all about?