It Came From Planet Architecture

Coming from humble Visual Basic 3.0 beginnings, by way of AmigaBasic, AppleSoft Basic, and Coleco Adam SmartBasic, I didn’t get a lot of exposure to formal programming practice.

One of the primary benefits of .NET is that it brings VB programmers into the fold – we’re now real programmers writing in a real language, using the same IDE as the C# and C++ guys. And like other real programmers, we are expected to use proper development patterns and practices, many of which were absorbed from the Java world. It’s a great opportunity for the masses of VB.NET developers to improve their skills and become more productive. However, there is a dark, non-productive side to the patterns and practices brigade: something Joel Spolsky calls architecture astronauts.

It’s a phenomenon I strongly associate with the Java world:

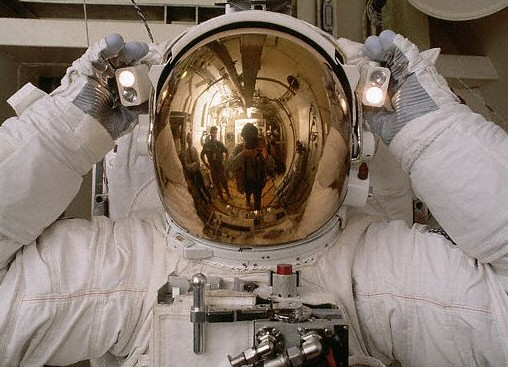

When you go too far up, abstraction-wise, you run out of oxygen. Sometimes smart thinkers just don’t know when to stop, and they create these absurd, all-encompassing, high-level pictures of the universe that are all good and fine, but don’t actually mean anything at all.

These are the people I call Architecture Astronauts. It’s very hard to get them to write code or design programs, because they won’t stop thinking about Architecture. They’re astronauts because they are above the oxygen level, I don’t know how they’re breathing. They tend to work for really big companies that can afford to have lots of unproductive people with really advanced degrees that don’t contribute to the bottom line.

Here’s the key distinction between an architecture astronaut and a practical developer: when you’re in the trenches proving your ideas by implementing them in real applications. The kind used by actual users. Christopher Baus articulates this best in doers vs. talkers:

Software isn’t about methodologies, languages, or even operating systems. It is about working applications. At Adobe I would have learned the art of building massive applications that generate millions of dollars in revenue. Sure, PostScript wasn’t the sexiest application, and it was written in old school C, but it performed a significant and useful task that thousands (if not millions) of people relied on to do their job. There could hardly be a better place to learn the skills of building commercial applications, no matter the tools that were employed at the time. I did learn an important lesson at ObjectSpace. A UML diagram can’t push 500 pages per minute through a RIP.

There are two types of people in this industry. Talkers and Doers. ObjectSpace was a company of talkers. Adobe is a company of doers. Adobe took in $430 million in revenue last quarter. ObjectSpace is long bankrupt.

Patterns and practices are certainly good things, but they should always be framed in the context of a problem you’re solving for the users. Don’t succumb to the dark side.