Did IE6 Make Web 2.0 Possible?

One of the cornerstones of Web 2.0 is the XMLHttpRequest object. It allows JavaScript to call back to a web server without incurring a traditional HTTP postback. It’s the heart and soul of AJAX, and it’s a completely proprietary feature Microsoft introduced along with IE 5.0 in March 1999. Supposedly it was introduced so the Exchange team could build Outlook Web Access.

The first mention of Mozilla and XMLHttpRequest I could find on Usenet is this post to netscape.public.mozilla.jseng from January 2000. XMLHttpRequest was eventually implemented in Mozilla 1.0, which was released in June 2002. It isn’t implemented as an exact copy of the IE version, however. The declaration is a little different. In IE, it’s an ActiveX object:

var req = new ActiveXObject("Microsoft.XMLHTTP");

In Firefox and Safari, it’s a native object:

var req = new XMLHttpRequest();

And things were quiet on that front until Google Suggest was revealed near the end of 2004. In April 2006, XMLHttpRequest was belatedly submitted to the W3C as a standard.

But how did we get here?

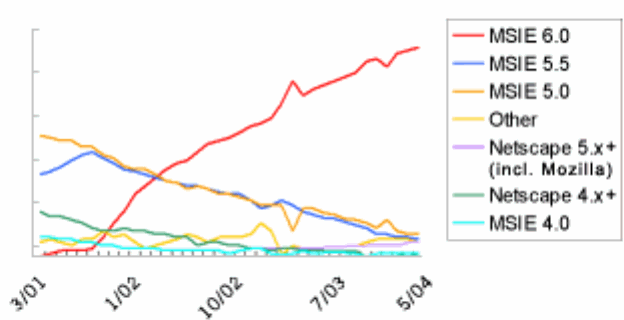

Google’s Zeitgeist used to break down Google searchers by browser and operating system. Unfortunately, they stopped reporting this after June 2004’s Zeitgeist. Here’s an enlarged version of the last browser share graph:

It’s a stark picture of how monoculture the browser world became between January 2001 and June 2004. Google is the best source of data for browser market share, in my opinion, because nothing is as egalitarian and universal as the number one search engine. I wonder why Google discontinued reporting this data? Was it a competitive advantage?

Google is a good source for this kind of data, but it isn’t the only one. there are dozens of different agencies and organizations offering browser market share statistics. Wikipedia has a comprehensive page that tracks browser market share across a multitude of different sources. Although opinions vary on the reliability of browser market share figures, a quick scan through all the data reveals one interesting commonality across all the data sources: IE6 market share peaked at around 95 percent sometime in mid-2004.

Ninety-five percent is an incredible number. Super-saturation for a single version of a browser was historically unheard of in the browser market; the progression of IE (and most other browsers) up to that point was steady and regular:

- Internet Explorer 1.0, August 1995

- Internet Explorer 2.0, November 1995

- Internet Explorer 3.0, August 1996

- Internet Explorer 4.0, September 1997

- Internet Explorer 5.0, March 1999

- Internet Explorer 5.5, July 2000

- Internet Explorer 6.0, August 2001

The next version of IE was never more than a year off. IE 7.0 is slated for release in early 2007; at that point, it will have been almost six years since Microsoft released a new version of Internet Explorer. The super-saturation of IE 6.0 is a direct consequence of Microsoft virtually abandoning development on IE.

If 95% of the world is browsing with IE 6, pursuing browser independence is a waste of time. If you don’t have to worry about browser independence, you are suddenly free to exploit advanced browser techniques like XMLHttpRequest. And, even more conveniently, alternative browsers have adopted XMLHttpRequest. Not that it mattered in late 2004, since IE6 still had 90 to 95 percent market share – depending on which figures you trust.

Surely Microsoft is concerned about the internet as an application platform, and thus, as an alternative to Windows applications. Some pundits think Microsoft was intentionally trying to cripple internet application development by halting all development on IE. Personally, I don’t subscribe to this theory. But if that was the plan, it backfired spectacularly. Having everyone on the same browser platform, with a 95 percent market share, didn’t create a stagnant development platform. The super-saturation and monoculture of IE6 from 2002 to 2004 created an incredibly rich, vibrant development platform where developers were free to push the capabilities of the browser to its limits. Without worrying about backward compatibility. Without writing thousands of if... else statements to accommodate a half-dozen alternative browsers.

If you subscribe to the “evil Microsoft” theory, Microsoft would have been far better off releasing new, mildly incompatible versions of Internet Explorer every year.

Ironic, isn’t it?