Books: Bits vs. Atoms

I adore words, but let’s face it: books suck.

More specifically, so many beautiful ideas have been helplessly trapped in physical made-of-atoms books for the last few centuries. How do books suck? Let me count the ways:

- They are heavy.

- They take up too much space.

- They have to be printed.

- They have to be carried in inventory.

- They have to be shipped in trucks and planes.

- They aren’t always available at a library.

- They may have to be purchased at a bookstore.

- They are difficult to find.

- They are difficult to search within.

- They can go out of print entirely.

- They are too expensive.

- They are not interactive.

- They cannot be updated for errors and addendums.

- They are often copyrighted.

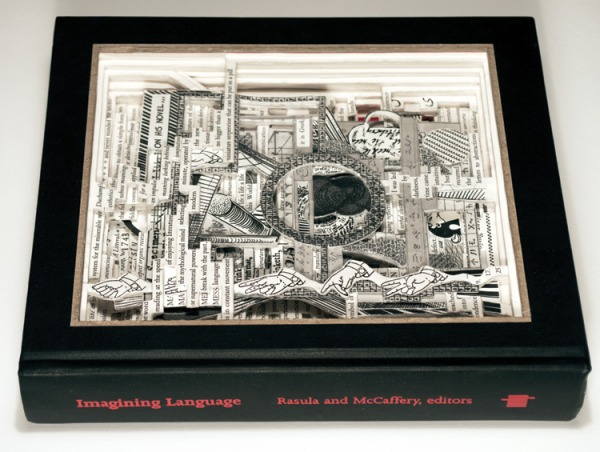

What’s the point of a bookshelf full of books other than as an antiquated trophy case of written ideas trapped in awkward, temporary physical relics?

Books should not be celebrated. Words, ideas, and concepts should be celebrated. Books were necessary to store these things, simply because we didn’t have any other viable form to contain them. But now we do.

Words Belong on the Internet

At the risk of stating the obvious, if your goal is to get a written idea in front of as many human beings as efficiently as possible, you shouldn’t be publishing dead tree books at all. You should be editing a wiki, writing a blog, or creating a website. That’s why the Encyclopedia Britannica officially went out of print in 2012, after a 244 year print run. In the straight-up match between paper and Web, the Encyclopedia Britannica lost. Big time.

The EB couldn’t cover enough: 65,000 topics compared to the almost 4M in the English version of Wikipedia.

Topics had to be consistently shrunk or discarded to make room for new information. E.g., the 1911 entry on Oliver Goldsmith was written by no less than Thomas Macaulay, but with each edition, it got shorter and shorter. EB was thus in the business of throwing out knowledge as much as it was in the business of adding knowledge.

Topics were confined to rectangles of text. This is of course often a helpful way of dividing up the world, but it is also essentially false. The “see also’s” and the attempts at synthetic indexes and outlines (Propædi) helped, but they were still highly limited, and cumbersome to use.

This is why the book scanning efforts of Google Books and The Internet Archive are so important – to unlock the knowledge trapped in all those books and place it online so the entire world can benefit.

In the never-ending human quest for communication, bits have won decisively over atoms. But bits haven’t completely replaced atoms for publishing quite yet; that will take a few more decades.

An Argument for the eBook

While the Internet is perfectly adequate for basic printed text juxtaposed with images and tables, it is a far cry from the beautiful, complex layout and typography of modern books. Sometimes the medium is part of the message. That’s what led computer scientists to create PostScript and TeX, systems of representing the printed page in code as pure mathematics that can scale infinitely, or at least to the best possible resolution of the particular device you’re viewing it on. Packaging written content into a special file format preserves these beautiful layouts so you can read the text as originally designed by the author.

It’s also fair to argue that writers should be fairly compensated for their work. Clearly nobody is going to pay 5 cents per web page. But there’s a long established commercial model of packaging a set of writing together into a coherent format, or “book,” and selling that.

You can’t always rely on the Internet being available. What if you have no Internet connectivity, or intermittent connectivity? You could periodically harvest a bunch of related web pages every month and package the current versions into a file. And that file can be stored and cached locally on laptops, phones, and servers all over the world. Local files have built in, persistent offline availability.

No, the Internet will not kill the book. But it will change their form permanently; books are no longer pages printed with atoms, they’re files printed with bits: eBooks.

The Trouble with Bits

The road from atoms to bits is not an easy one, and we’re only at the beginning of this journey. eBooks are vastly more flexible than printed books, but they come with their own set of tradeoffs:

- They always require a reading device.

- They cannot be loaned to friends.

- They cannot be resold to others.

- They cannot be donated to libraries.

- They may be encumbered with copy protection.

- They may be in a format your reader cannot understand.

- They may refuse to load for any reason the publisher deems necessary.

- They may have incomplete or broken or obsolete layout.

- They may have low-resolution bitmapped images that are inferior to print.

- They may be a substantially worse reading experience than print except on very high resolution reading devices.

The copy protection issue alone is deeply troubling; with eBooks, book publishers now have an unprecedented level of control over when, where, and how you can read their books. In the world of atoms, once the book is shipped out, the publisher cedes all control to the reader. Once you’ve bought that physical book, you can do with it whatever you will: read it, burn it, photocopy it (for personal use), share it, resell it, loan it, donate it, even throw it at passers-by as a makeshift weapon. But in the world of bits, the publisher has an iron grip over their eBook, which isn’t so much sold to you as “licensed” for your use, maybe even only for specific devices like an Amazon Kindle or an Apple iPad. And they can silently remove the book from your device at their whim.

In the brave new world of eBooks, book publishers are waking up drunk with newfound power. And honestly I can’t say I blame them. After centuries of publishers having virtually no control at all over the books they publish, they’ve now been granted near total control.

How Much Do eBooks Cost?

Consider one of my favorite books, the classic Don’t Make Me Think. How much does it cost to buy, as an eBook or otherwise?

| Amazon print new | $22.88 |

| Amazon print used | $13.98 |

| Amazon eBook | $14.16 |

| Publisher eBook | $25.60 |

| Apple eBook | $33.16 |

Except for Amazon, all the eBooks are more expensive than the print version. This… makes no sense. How can the bits in the digital version, which require no printing, no shipping, no physical storage whatsoever, be more expensive than the atoms?

What Do eBooks Look Like?

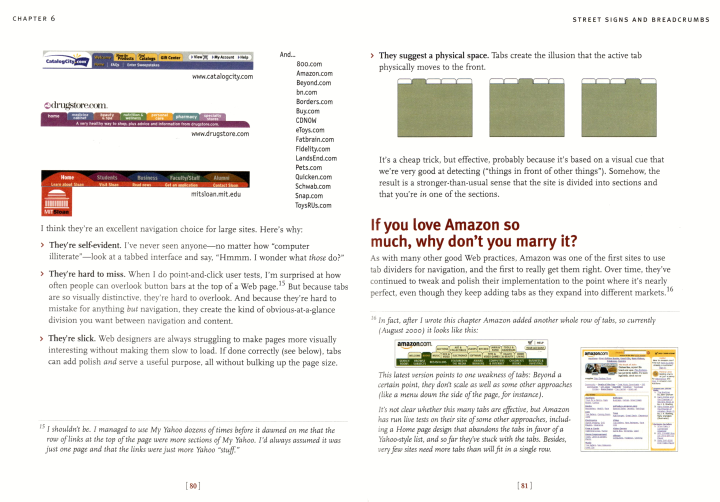

What you actually end up reading when you buy the eBook can vary wildly. Here are pages 80 and 81 of my print copy of Don’t Make Me Think. I attempted to take a photograph of the book, then realized it’s incredibly difficult to take a decent picture of two pages of a book for a photography noob like myself, so I manually scanned the pages in instead.

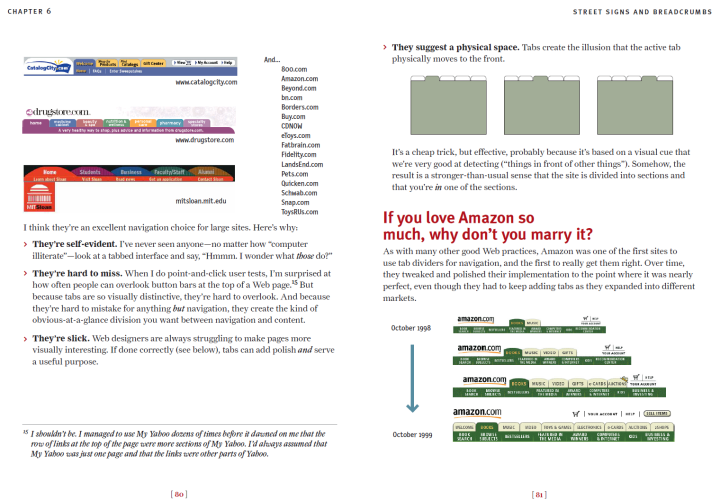

If you buy the eBook from the publisher, you get a PDF which appears to be based on the exact same data used to print the book. Pages 80 and 81 are nearly identical to print, with page numbers, footnotes, layout and typography completely intact. (There are some unrelated minor differences on page 81 because the print version is from the second edition.)

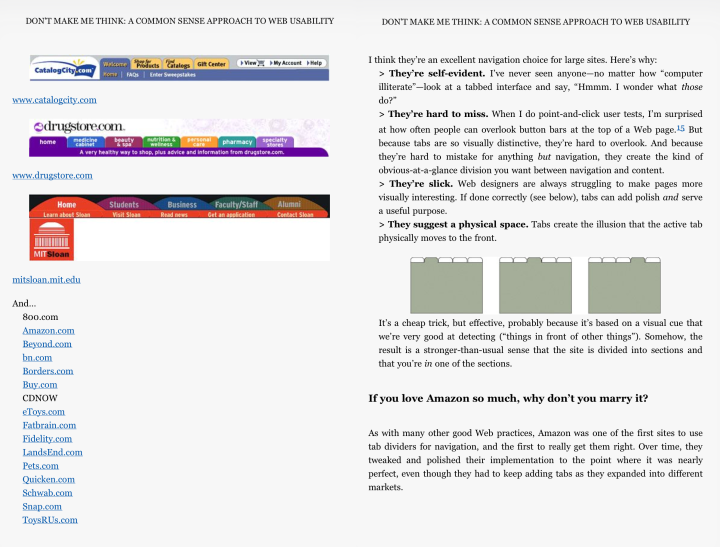

But when you buy the eBook from Amazon, you get a proprietary eBook format which contains very little of the original formatting. Pages 80 and 81 are quite different. The footnotes are gone. The title font and font colors are lost. The layout and spacing is completely off, and to my eye the page frankly looks a little broken.

When you buy the book from Apple, you get yet another proprietary eBook format. For comparison, here’s page 3 of Don’t Make Me Think from the publisher’s PDF, which as we’ve previously established is very nearly the same as print.

I downloaded the sample chapter of Don’t Make Me Think from Apple’s iBooks, and it appears to be an even worse representation than Amazon’s. I have all the same criticisms of Amazon’s eBook format here – page 3 has broken layout, no footnotes, missing title fonts and colors, plus now it takes four, yes, four pages to read that very same single print page.

So eBooks Suck, Too?

With Don’t Make Me Think, I intentionally chose a book that highlights the remaining gap between atoms and bits in books. I’ve read dozens of other eBooks on Kindle and iPad, and generally the experience is good. For books that are entirely text, with very little layout, the various eBook formats do a great job. This may very well be a majority of books in the world. All eBook formats handle text and basic fonts perfectly fine. But then, so does the Internet. If an eBook can’t outperform the Internet at layout, it loses one of the strongest arguments in its favor.

Still, there’s no way Amazon’s or Apple’s current eBook versions of Don’t Make Me Think are suitable replacements for the print version. Worse, you won’t even know what you’ll be missing unless you download a sample and compare it with the print version, as I have. That’s disappointing, because part of the joy a book brings to the words inside is by expertly packaging those words into a whole experience. If an eBook can’t capture the nuance of the layout at least as well as a hoary old PDF does, again, why bother?

We, as readers, are easily giving up as much as we’re getting in the transition from books made of atoms to eBooks made of bits. To make it worthwhile, I believe publishers need to do two things:

- eBooks should be inexpensive. Because I can’t loan them (with rare exceptions), because I can’t resell them, because I can’t buy a cheaper used copy, because I’m only licensed to read them at all on “supported” readers under whatever terms the publishers will allow me to, an eBook simply has less utility and value to me. Right now, eBooks are far less flexible than physical books and therefore a worse value. Yet they are far cheaper to produce and sell for everyone involved. The pricing absolutely has to reflect this. If I can get a used copy of a book for less than the eBook, no sale. If I can get a new copy of a book for less than the eBook, no sale and screw you.

- eBooks should be a near-perfect replica of the print book. With the advent of the iPad 3, it is finally possible for eBook readers to provide nearly the same visual fidelity as the print book. I don’t want to spend money on an eBook with broken, inferior formatting and typography and layout compared to the print edition. Give me an eBook that I can potentially hand down to my children with the same confidence I could give them a print book, 30 years from now, and know that I am not totally compromising the experience.

Because I love words, I want to love eBooks. I want to buy lots and lots of eBooks. But unless the publishers are willing to treat eBooks with the same respect and care that they give to their printed books – and most importantly of all, adjust their pricing to reflect the brave new economy of bits, and not an antiquated economy of atoms – they’re destined to eventually suffer the same fate as the Encyclopedia Britannica.