UML, Circuit Diagrams, and God’s Rules

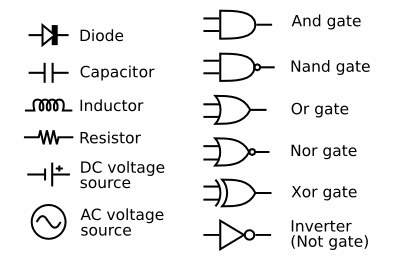

Very few software engineers use UML symbols to design software, but electrical engineers regularly use circuit symbols to design electronics:

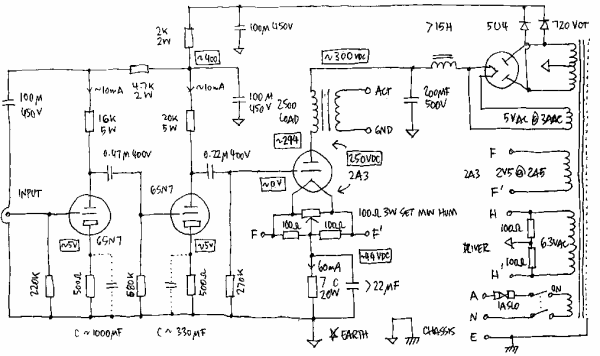

Circuit symbols are constructed into circuit diagrams – the the visual language of electricity:

If circuit diagrams are a standard, universally understood way to talk about electronics, why doesn’t UML enjoy the same currency for software development?

Well, one obvious difference is that software, unlike electricity, isn’t subject to God’s laws.* And God didn’t invent x86. Software development is far less amenable to formal diagrams because, well, it’s something we just made up. And we keep changing the rules all the time. As Brooks points out in The Mythical Man-Month, software developers are essentially playing the role of God:

Why is programming fun? What delights may its practitioner expect as his reward?

First is the sheer joy of making things. As the child delights in his mud pie, so the adult enjoys building things, especially things of his own design. I think this delight must be an image of God’s delight in making things, a delight shown in the distinctiveness of each leaf and each snowflake.

Second is the pleasure of making things that are useful to other people. Deep within, we want others to use our work and to find it helpful. In this respect the programming system is not essentially different from the child’s first clay pencil holder “for Daddy's office.”

Third is the fascination of fashioning complex puzzle-like objects of interlocking moving parts and watching them work in subtle cycles, playing out the consequences of principles built in from the beginning. The programmed computer has all the fascination of the pinball machine or the jukebox mechanism, carried to the ultimate.

Fourth is the joy of always learning, which springs from the nonrepeating nature of the task. In one way or another the problem is ever new, and its solver learns something: sometimes practical, sometimes theoretical, and sometimes both.

Finally, there is the delight of working in such a tractable medium. The programmer, like the poet, works only slightly removed from pure thought-stuff. He builds his castles in the air, from air, creating by exertion of the imagination. Few media of creation are so flexible, so easy to polish and rework, so readily capable of realizing grand conceptual structures. (As we shall see later, this tractability has its own problems.)

Yet the program construct, unlike the poet’s words, is real in the sense that it moves and works, producing visible outputs separately from the construct itself. It prints results, draws pictures, produces sounds, moves arms. The magic of myth and legend has come true in our time. One types the correct incantation on a keyboard, and a display screen comes to life, showing things that never were nor could be.

Programming then is fun because it gratifies creative longings built deep within us and delights sensibilities we have in common with all men.

Software developers do not have a monopoly on creativity. A clever circuit is no less imaginative than a clever algorithm. But software development is a “tractable medium.” If we decide the speed of light is not to our liking, we just change it. Imagine the difficulty an electrical engineer would have working on your circuit diagram if, on that diagram, you had changed something fundamental, like the conductivity of copper.

But even with the helpful constraint of God’s rules, circuit diagrams are still idealized representations of the final product. You need a printed circuit board to implement the circuit diagram – and the translation from circuit diagram into PCB typically involves a lot of real-world compromises.

This is not to say that formal software diagramming systems like UML aren’t useful in software engineering. They can be. But they’ll never be as useful as circuit diagrams are to electrical engineers.