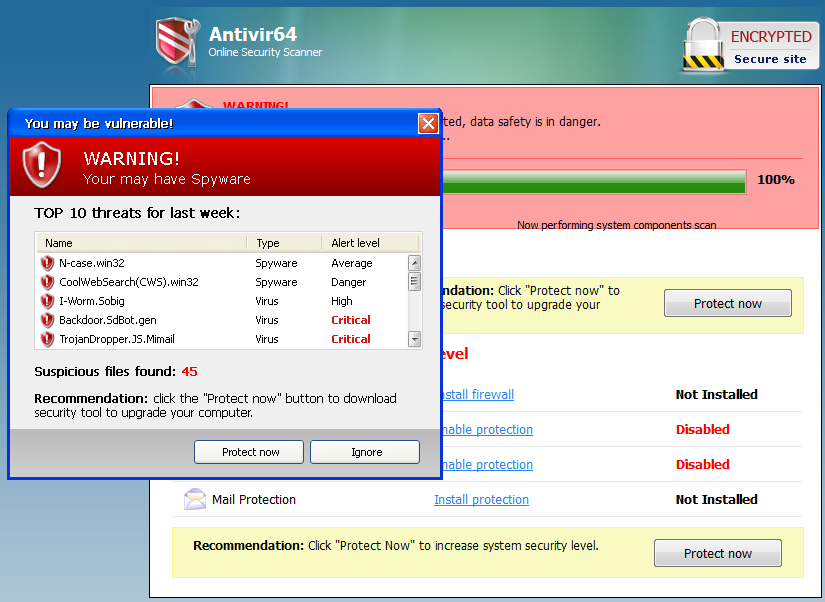

security

Cross-Site Request Forgeries and You

As the web becomes more and more pervasive, so do web-based security vulnerabilities. I talked a little bit about the most common web vulnerability, cross-site scripting, in Protecting Your Cookies: HttpOnly. Although XSS is incredibly dangerous, it’s a fairly straightforward exploit to understand. Do not allow users to insert