Although I am generally platform agnostic, I make no secret of the fact that I am primarily a Microsoft developer. In a way, I grew up with Microsoft-- as a teenager, I cut my programming teeth on the early microcomputer implementations of Microsoft BASIC. And I spent much of my professional life writing Visual Basic code. When Microsoft rebooted their programming franchise with .NET in 2003, I was thrilled and reinvigorated, glad to finally have a viable exit strategy from the glass house that was Visual Basic.

As a developer who grew up on a steady diet of Microsoft tools, I never understood the pockets of rabid anti-Microsoft sentiment in the programming community. To me, Microsoft was the least of all possible commercial evils, a generally benevolent dictatorship. Humor me for a moment and imagine replacing Microsoft with one of its competitors: Sun, IBM, Oracle, or Apple. I don't know about you, but those alternate histories send a chill up my spine. Yes, Microsoft is a near-monopoly, but as giant, evil monopolistic corporations go, you could do a lot worse. Microsoft is far from perfect, but they generally do the right thing as far as I'm concerned.

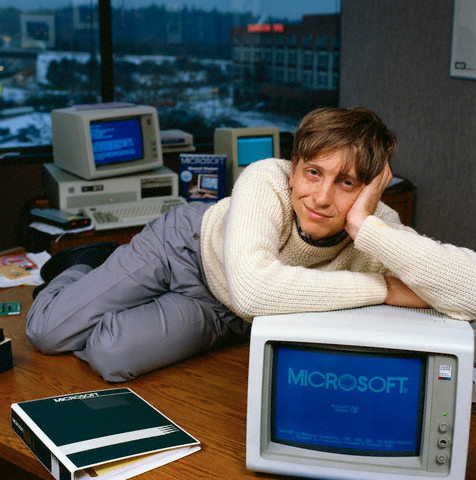

Microsoft has always been a developer-centric company to their very core. From Steve Ballmer's developers, developers, developers, to Bill Gates' centerfold shot, it's always been abundantly clear that Microsoft is a company which prides itself on taking care of its core constituency: developers.

Although I'm still satisfied with my place in the Microsoft development universe, some developers desperately want off the Microsoft treadmill. Mike Gunderloy is a notable example:

I've spent the bulk of the last fifteen years developing some amount of reputation and expertise in the Microsoft universe, having published dozens of books and hundreds of articles, worked as an editor and consultant, written (as a subcontractor) parts of various Microsoft products, and so on. I'm also the editor of the Larkware site, which tracks news in the Microsoft software world for developers.Unfortunately, over that time I've also come to the conclusion that, even though it is staffed largely by smart and ethical people, Microsoft itself represents a grave threat to the future of software development through its increasing inclination to stifle competition through legal shenanigans. Its recent attempt to claim that no one can implement a user interface that looks anything like the Office 2007 ribbon without licensing some nebulous piece of intellectual property represents a new low in this regard.

I'm in a bit of a bind. Unlike fifteen years ago, I've got a family, including four kids, and I can't afford to just walk out on a career that brings in good money. But I rather desperately want to find an alternative. This blog will record some of my explorations as I hunt around in other corners of the software world, trying to decide if there's a viable business plan for me that can include weaning myself off of Microsoft software.

Mike started a new blog, A Fresh Cup, where he's reinventing himself as an open-source developer. If you were wondering why the content at Larkware's Daily Grind has degenerated so much recently (and boy, has it ever), now you know. His heart's just not in it any more.

I can understand where Mike is coming from. Microsoft releases new technology at a blistering pace, and keeping up-- not to mention dealing with all the obsolete baggage you're carrying around-- is half the challenge. Just take a look at the stack I have to install on my development machine to do development work in .NET 3.0:

- Windows Vista

- Visual Studio 2005

- Visual Studio 2005 Team Explorer (source control)

- Orcas Extensions for Visual Studio 2005 (WPF & WCF project templates)

- SQL Server Express SP2

- Visual Studio 2005 SP1

- Visual Studio 2005 SP1 Update for Vista

- ASP.NET 2.0 AJAX Extensions 1.0

- Expression Blend

Historically, I've used Microsoft development environments because they made my life easier. It's hard to look at this list and see how it's any easier than the open source alternatives. I also begin to look longingly at the open source developers who have been plugging away productively in Perl or Python over the last five years. Sometimes, you wonder if choosing an environment where things change more slowly isn't a better long term evolutionary decision. Perhaps there's a kernel of truth in Paul Graham's sensationalist Microsoft is Dead article: can you even name any startups that use Microsoft development tools?

So part of me agrees with Mike. To paraphrase Chris Rock: I'm not saying he should have given up on Microsoft. But I understand.

Mike's certainly entitled to take whatever steps he deems necessary for his professional development. Still, his attitude frustrates me, because it falls so egregiously into the stereotypical, religious love/hate dichotomy that I've observed again and again in software developers. You either love Microsoft and use exclusively Microsoft products, or you hate Microsoft, and you vow never to use any of their products ever again. There's nothing in between. No middle ground. Why does it have to be an all or nothing proposition? As far as I'm concerned, every software developer, regardless of what's on their tool belt, has the same goal: to craft useful computer software that delights users. We're allies, not enemies. Friendly rivalry I can understand. But the rabid partisanship that I typically see-- on both sides of the fence-- isn't helping us.

I also find that both the Microsoft community and the open-source communities are far too insular and provincial. I had the great pleasure of meeting Miguel de Icaza at MIX this year. Miguel is one of my heroes, as he was instrumental in bringing .NET to the world of open source with the Mono project. What truly surprised me, though, was how few MIX attendees knew who Miguel was, despite his groundbreaking contribution to the .NET programming ecosystem. To me, he's famous. A celebrity. But because Miguel has roots in the open-source community, he barely exists to the majority of Microsoft-centric developers. They didn't even know who he was! And those who did recognize him had about a 50/50 chance of disliking him on principle. As Miguel pointed out during the open source panel, he's disliked by both camps: open-source zealots think he's sold out to Microsoft, and Microsoft zealots think he's destroying the value of the .NET platform.

This is wrong. This is not the way things should be.

As a software developer, you're doing yourself a disservice by pledging allegiance to anything other than yourself and your craft-- whether it's Microsoft or the principle of free software. Stop with the us vs. them mentality. Let go of the partisanship. We're all in this thing together.

I'm a pragmatist. For now, I choose to live in the Microsoft universe. But that doesn't mean I'm ignorant of how the other half lives. There's always more than one way to do it, and just because I chose one particular way doesn't make it the right way-- or even a particularly good way. Choosing to be provincial and insular is a sure-fire path to ignorance. Learn how the other half lives. Get to know some developers who don't live in the exact same world you do. Find out what tools they're using, and why. If, after getting your feet wet on both sides of the fence, you decide the other half is living better and you want to join them, then I bid you a fond farewell.

But either way, we're still friends.

Discussion