Living the Dream: Rock Band

I’m a huge fan of the Guitar Hero series. After reading the first reviews in November 2005, I rushed out to get one of the few available copies at my local Best Buy. It was an obscure title at the time – I had no idea it was even being released until I read the initial reviews, and I’m a fan of the rhythm genre. Guitar Hero is now such a massive success that everyone reading this has probably at least heard of it. It achieved pop culture critical mass, which is the ultimate and final level of success for any video game. It’s what every game aspires to, and precious few achieve.

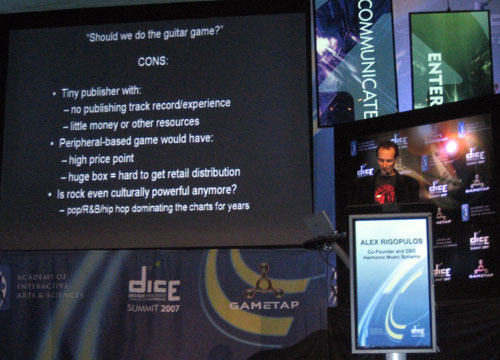

But it was far from a foregone success when it was under development. In fact, Guitar Hero was a highly questionable software development project from a publisher’s perspective:

- New, unproven franchises are risky.

- Games that require peripherals to play don’t typically sell well.

- Games that cost $70 - $80 don’t typically sell well.

- Games with a giant honking box tend to suffer for lack of shelf space.

- The Japanese title “Guitar Freaks,” a very similar game, flopped in the US.

Beyond that, the studio behind the game, Harmonix, had a poor track record. Their previous two rhythm games, Frequency and Amplitude, were not exactly hits. Despite great play tester impressions, positive reviews and many design awards, both games sold, in the words of co-founder Alex Rigopulos, “mouse nuts.”

This disconnect between creative output and sales took its toll on the team, as Alex explained in a recent interview:

It’s torture for the creative team that’s making the game, because when you make a game that the reviewers are loving and the play testers love it and whatnot, you feel like just on a creative level that you’ve succeeded. But as I mentioned this morning, it’s only half the battle, because if you make an experience that can’t be effectively marketed, then you’re just dramatically capping the number of people who will ever have access to that experience. For us, it was really hard to go through that experience, but we came out of it having learned an important lesson, which is that we needed to think up how to sort of wrap up these experiences in a form that sort of made it easier to reach out to a wider audience of people.

Alex gave a talk at DICE 2007 where he explained the internal debate over Guitar Hero in slide form.

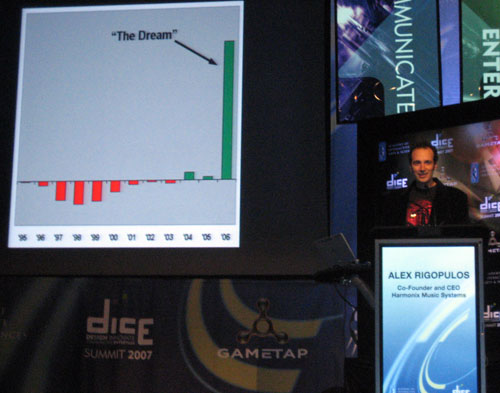

This graph of twelve years of Harmonix’ financial results illustrates, as Alex labels it, “The Dream.”

It took Harmonix ten full years to finally find success with 2005’s Guitar Hero, through dogged persistence pursuing the rhythm game genre.

Harmonix went on to create Guitar Hero II, which greatly amplified the multiplayer and polished the overall experience. After that, there was a schism – the Guitar Hero franchise, including Guitar Hero III, is in the hands of different developers. Harmonix went on to develop the innovative Rock Band. Instead of the two player bass and lead guitar multiplayer of Guitar Hero, in Rock Band, you have four players – bass guitar, lead guitar, drums, and vocals.

It’s a continuing evolution of the dream:

My biggest hope is that this game deepens people’s connection with the rock music that they love. Playing this game changes people’s understanding of music. Most people, they listen to rock, they don’t even separate the music into the different instrumental components. They don’t hear the drums and the bass and the guitar separately, it all sort of blends together into a mash for them. Playing this game changes that. Playing this game changes the way that people hear rhythms. It changes the way they hear the interrelation between different parts. The act of playing it just connects people in a very visceral, physical way with the music that they don’t otherwise experience. So really what it’s all about for us is just making peoples’ connection with the music that they love much more profound. I really do think that on a mass scale millions of people will understand and feel music in a different way because of this game.

I’d like to think a big part of Harmonix’ success is – to steal a phrase from the greatly missed Kathy Sierra – their dedication not to gameplay, not to code, not to sales, but to helping users kick ass:

Phrase everything in terms of the user’s personal experience rather than the product. Keep asking, no matter what, “So, how does this help the user kick ass?” and “How does this help the user do what he really wants to do?” Don’t focus on what the user will think about the product, focus everyone around you on what the user will think about himself as a result of interacting with it.

This is how all software should be written: with the user’s goals at the forefront.

There’s absolutely no better way to experience the sublime feeling of personal success Kathy is describing here than to play Rock Band with your friends and coworkers. If you haven’t tried it yet, I envy the experience you’re about to have.