How Not to Conduct an Online Poll

Inside the Precision Hack is a great read. It’s all about how the Time Magazine World’s Most Influential People poll was gamed. But the actual hack itself is somewhat less impressive when you start digging into the details.

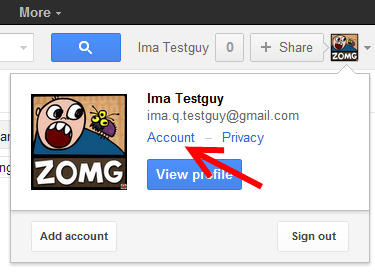

Here’s the voting UI for the Time poll in question.

Casting a vote submits a HTTP GET in the form of:

http://www.timepolls.com/contentpolls/Vote.do ?pollName=time100_2009&id=1883924&rating=1

Where id is a number associated with the person being voted for, and rating is how influential you think that person is from 1 to 100. Simple enough, but Time’s execution was... less than optimal.

In early stages of the poll, Time.com didn’t have any authentication or validation – the door was wide open to any client that wanted to stuff the ballot box.

Soon afterward, it was discovered that the Time.com Poll didn’t even range check its parameters to ensure that the ratings fell within the 1 to 100 range

The outcome of the 2009 Time 100 World’s Most Influential People poll isn’t that important in the big scheme of things, but it’s difficult to understand why a high profile website would conduct an anonymous worldwide poll without even the most basic of safeguards in place. This isn’t high security; this is web 101. Any programmer with even a rudimentary understanding of how the web works would have thought of these exploits immediately.

Without any safeguards, wannabe “hackers” set out to game the poll in every obvious way you can think of. Time eventually responded – with all the skill and expertise of... a team who put together the world’s most insecure online poll.

Shortly afterward, Time.com changed the protocol to attempt to authenticate votes by requiring a key be appended to the poll submission URL. The key consisted of an MD5 hash of the URL + a secret word (aka ‘the salt’). [hackers eventually] discovered that the salt [. . .] was poorly hidden in Time.com’s voting flash application. With the salt extracted, the autovoters were back online, rocking the vote.

So-called secret poorly hidden on the client: check!

Another challenge faced by the autovoters was that if you voted for the same person more often than once every 13 seconds, your IP would be banned from voting. However, it was noticed that you could cycle through votes for other candidates during those 13 seconds. The autovoters quickly adapted to take advantage of this loophole, interleaving up-votes for moot with down-votes for the competition -- ensuring that no candidate received a vote more frequently than once every 13 seconds, maximizing the voting leverage.

Sloppy, incomplete IP throttling: check!

At this point, here’s the mental image I had of the web developers running the show at time.com:

Remember my advice from design for evil?

When good is dumb, evil will always triumph.

Well, here’s your proof. I’m not sure they come any dumber than these clowns.

The article goes on to document how the “hackers” exploited these truck sized holes in the time.com online voting system to not only put moot on top, but spell out a little message, too, for good measure:

Looking at the first letters of each of the top 21 leading names in the poll we find the message “marblecake, also the game.” The poll announces (perhaps subtly) to the world, that the most influential are not the Obamas, Britneys or the Rick Warrens of the world, the most influential are an extremely advanced intelligence: the hackers.

It’s a nice sentiment, I suppose. But is it really a precision hack when your adversaries are incompetent? If you want to read about a real hack – one that took “extremely advanced intelligence” in the face of a nearly unstoppable adversary – try the black Sunday hack. Now that’s a hack.

Update: A second article describing more Time poll hilarity. Now with 100% more CAPTCHA!