Trespasser Postmortem

I love playing videogames, but I have no illusions whatsoever of being talented enough to write videogames. Game developers live a hard life, and not just because the industry is notoriously abusive. Even the most brilliant minds can get bogged down in the morass of complexity that is game development. Take, for example, 1998’s Trespasser. The design goals for the game were impressive even by today’s standards, as documented in the Gamasutra postmortem (login required; use BugMeNot credentials or disable JavaScript):

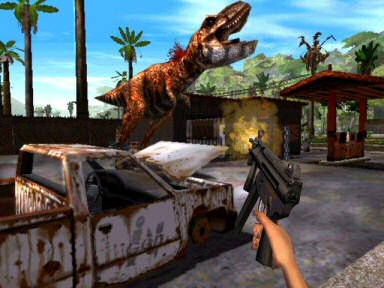

The pie-in-the-sky concept for Trespasser was an outdoor engine with no levels, a complete rigid-body physics simulation, and behaviorally-simulated and physics-modeled dinosaurs. The underlying design goal was to achieve a realistic feel through consistency of looks and behavior. Having an abandoned island setting was a useful way to exclude anything which did not seem possible to simulate, such as flexible solids like cloth and rope, wheeled vehicles, and the effects of burning, cutting, and digging.

The game would play from a first-person perspective, and you would experience the environment through a virtual body to avoid the “floating gun” feeling prevalent in the Wolfenstein breed of first person games. Combat would be less important than in a shooter, and dinosaurs would be much more dangerous than traditional first-person shooter enemies. The point of the game would be exploration and puzzle-solving, and when combat happened, it would more often involve frightening opponents away by inflicting pain than the merciless slaughter of every moving creature.

Likewise, though we would only have a few different types of dinosaurs, the dinosaur AI system would allow them to react to each other and the player in a large variety of ways, choosing appropriate responses depending on their emotional state. Sophisticated, fully-interruptible scenes would occur spontaneously rather than requiring large amounts of scripting, and observing the food chain in action would be as absorbing as playing the game itself. Interacting with the limited but rich features would lead to “emergent gameplay,” the grail for many of Looking Glass’ best thinkers since Underworld I shipped and fans began to write in describing favorite moments - moments which had not been specifically designed or even experienced by the team itself.

All of the GamaSutra postmortems are fascinating war stories of extremely challenging software development projects. Like Steve McConnell’s list of classic development mistakes, it’s worth reading through a few of these, at least for games you’re interested in. Trespasser is a worthy starting point because it was so far ahead of its time, and because it’s also one of the most notorious failures in PC gaming history.

Personally, I loved Trespasser, even though it was a perplexing mish-mash of 50 percent genius and 50 percent unfinished beta. It didn’t help that the game was released right as hardware 3D acceleration was becoming mainstream, either. But the deepest problems had nothing to do with software, and everything to do with peopleware. Here are a few highlights from the postmortem:

The biggest indication that Trespasser had game design problems was the fact that it never had a proper [gameplay] design spec. For a long time, the only documents which described the gameplay were a prose-based walkthrough of what the main character would do as she went through the game, and a short design proposal listing the keys which would be used and some rough ideas of what gameplay might actually be. These documents were created before any playable technology existed and were based on promises of how that technology was supposed to work.

When the game had a complete team and had essentially entered production, the prose walkthrough was used to create level maps and more-complete puzzle descriptions. However, by this point in the project artists had been building assets for nearly a year and programmers had been implementing code for even longer, and the gameplay was being crafted as a primarily engineering-driven rather than design-driven process. Engineering-driven software design can work fine when the gameplay needs of the final product are extremely light and flexible, but in the case of Trespasser, where we were trying to achieve a specific and complex gameplay, it ended up being the source of many of our problems.

The general awkwardness of team relations was exacerbated by having a key part of the whole project – the physics – written by the project leader. It used to be that it was possible to both run a project and contribute key work to it, but with a game as complicated and a team as large as Trespasser, it was not reasonable to expect that this would be possible. Beyond being a nigh-impossible task, it also put the department heads of the project, especially the lead programmer, in an unenviable and difficult position. When the physics code was continuously delayed and unsatisfactory, there was no easy way to take action to fix those problems. No lead programmer should be expected to tell their boss that he had better get his work done or take some drastic action to get the project back on schedule. [. . .] Perhaps worst of all were the personality conflicts which arose – after a while, it became impossible to even attempt to raise concerns about the physics code without in a constructive rather than confrontational manner. Many on the team began to go out of their way to avoid dealing with the issue at all, but this only allowed the problems to continue growing.

Sound familiar? The project lead on Trespasser was Seamus Blackley, who later went on to work for Microsoft, where he created and evangelized the Xbox.

(if you liked this postmortem, I highly recommend the book Postmortems from Game Developer: Insights from the Developers of Unreal Tournament, Black and White, Age of Empires, and Other Top-Selling Games, which is a giant collection of in-depth postmortems like the one on Trespasser.)