user experience

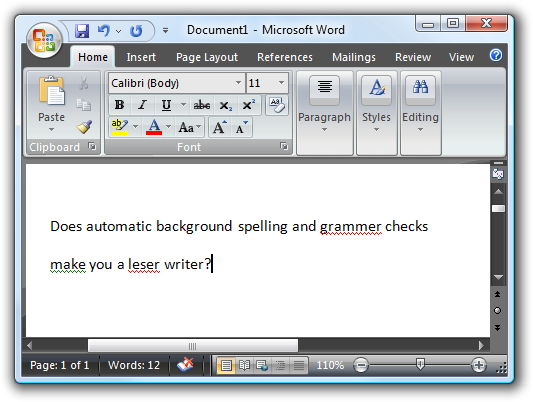

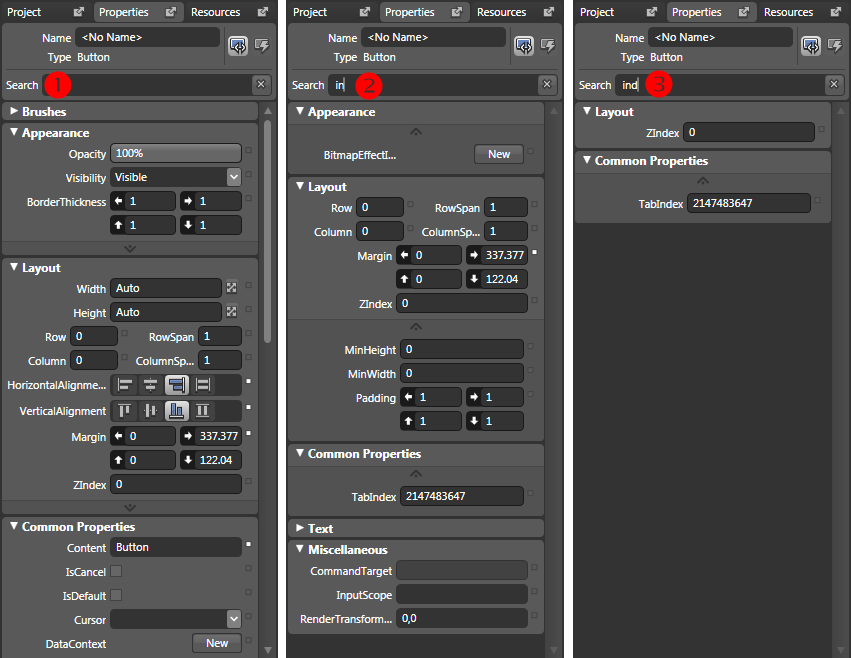

Incremental Feature Search in Applications

I’m a big fan of incremental search. But incremental search isn’t just for navigating large text documents. As applications get larger and more complicated, incremental search is also useful for navigating the sea of features that modern applications offer. Office 2007’s design overhaul is arguably one of