When I first chose my own adventure, I didn't know what working remotely from home was going to be like. I had never done it before. As programmers go, I'm fairly social. Which still means I'm a borderline sociopath by normal standards. All the same, I was worried that I'd go stir-crazy with no division between my work life and my home life.

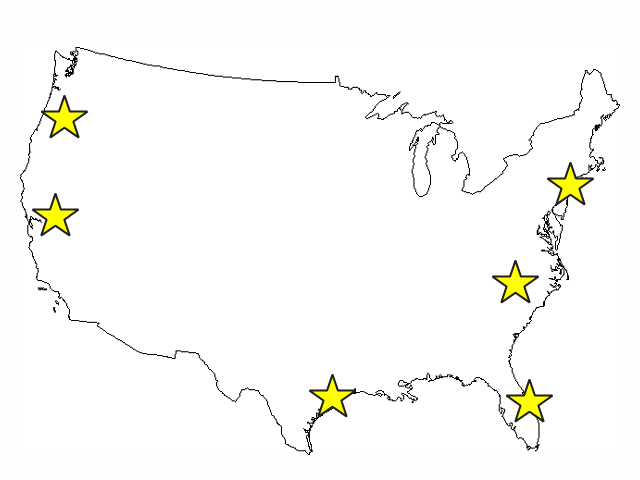

Well, I haven't gone stir-crazy yet. I think. But in building Stack Overflow, I have learned a few things about what it means to work remotely – at least when it comes to programming. Our current team encompasses 5 people, distributed all over the USA, along with the team in NYC.

My first mistake was attempting to program alone. I had weekly calls with my business partner, Joel Spolsky, which were quite productive in terms of figuring out what it was we were trying to do together – but he wasn't writing code. I was coding alone. Really alone. One guy working all by yourself alone. This didn't work at all for me. I was unmoored, directionless, suffering from analysis paralysis, and barely able to get motivated enough to write even a few lines of code. I rapidly realized that I'd made a huge mistake in not having a coding buddy to work with.

That situation rectified itself soon enough, as I was fortunate enough to find one of my favorite old coding buddies was available. Even though Jarrod was in North Carolina and I was in California, the shared source code was the mutual glue that stuck us together, motivated us, and kept us moving forward. To be fair, we also had the considerable advantage of prior history, because we had worked together at a previous job. But the minimum bar to work remotely is to find someone who loves code as much as you do. It's … enough. Anything else on top of that – old friendships, new friendships, a good working relationship – is icing that makes working together all the sweeter. I eventually expanded the team in the same way by adding another old coding buddy, Geoff, who lives in Oregon. And again by adding Kevin, who I didn't know, but had built amazing stuff for us without even being asked to, from Texas. And again by adding Robert, in Florida, who I also didn't know, but spent so much time on every single part of our sites that I felt he had been running alongside our team the whole way, there all along.

The reason remote development worked for us, in retrospect, wasn't just shared love of code. I picked developers who I knew – I had incontrovertible proof – were amazing programmers. I'm not saying they're perfect, far from it, merely that they were top programmers by any metric you'd care to measure. That's why they were able to work remotely. Newbie programmers, or competent programmers who are phoning it in, are absolutely not going to have the moxie necessary to get things done remotely – at least, not without a pointy haired manager, or grumpy old team lead, breathing down their neck. Don't even think about working remotely with anyone who doesn't freakin' bleed ones and zeros, and has a proven track record of getting things done.

While Joel certainly had a lot of high level input into what Stack Overflow eventually became, I only talked to him once a week, at best (these calls were the genesis of our weekly podcast series). I had a strong, clear vision of what I wanted Stack Overflow to be, and how I wanted it to work. Whenever there was a question about functionality or implementation, my team was able to rally around me and collectively make decisions we liked, and that I personally felt were in tune with this vision. And if you know me at all, you know I'm not shy about saying no, either. We were able to build exactly what we wanted, exactly how we wanted.

Bottom line, we were on a mission from God. And we still are.

So, there are a few basic ground rules for remote development, at least as I've seen it work:

- The minimum remote team size is two. Always have a buddy, even if your buddy is on another continent halfway across the world.

- Only grizzled veterans who absolutely love to code need apply for remote development positions. Mentoring of newbies or casual programmers simply doesn't work at all remotely.

- To be effective, remote teams need full autonomy and a leader (PM, if you will) who has a strong vision and the power to fully execute on that vision.

This is all well and good when you have a remote team size of three, as we did for the bulk of Stack Overflow development. And all in the same country. Now we need to grow the company, and I'd like to grow it in distributed fashion, by hiring other amazing developers from around the world, many of whom I have met through Stack Overflow itself.

But how do you scale remote development? Joel had some deep seated concerns about this, so I tapped one of my heroes, Miguel de Icaza – who I'm proud to note is on our all-star board of advisors – and he was generous enough to give us some personal advice based on his experience running the Mono project, which has dozens of developers distributed all over the world.

At the risk of summarizing mercilessly (and perhaps too much), I'll boil down Miguel's advice the best I can. There are three tools you'll need in place if you plan to grow a large-ish and still functional remote team:

-

Real time chat

When your team member lives in Brazil, you can't exactly walk by his desk to ask him a quick question, or bug him about something in his recent checkin. Nope. You need a way to casually ping your fellow remote team members and get a response back quickly. This should be low friction and available to all remote developers at all times. IM, IRC, some web based tool, laser beams, smoke signals, carrier pigeon, two tin cans and a string: whatever. As long as everyone really uses it.

We're currently experimenting with Campfire, but whatever floats your boat and you can get your team to consistently use, will work. Chat is the most essential and omnipresent form of communication you have when working remotely, so you need to make absolutely sure it's functioning before going any further.

-

Persistent mailing list

Sure, your remote team may know the details of their project, but what about all the other work going on? How do they find out about that stuff or even know it exists in the first place? You need a virtual bulletin board: a place for announcements, weekly team reports, and meeting summaries. This is where a classic old-school mailing list comes in handy.

We're using Google Groups and although it's old school in spades, it works plenty well for this. You can get the emails as they arrive, or view the archived list via the web interface. One word of caution, however. Every time you see something arrive in your inbox from the mailing list you better believe, in your heart of hearts, that it contains useful information. The minute the mailing list becomes just another "whenever I have time to read that stuff", noise engine, or distraction from work … you've let someone cry wolf too much, and ruined it. So be very careful. Noisy, argumentative, or useless things posted to the mailing list should be punishable by death. Or noogies.

-

Voice and video chat

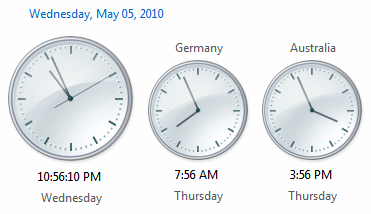

As much as I love ASCII, sometimes faceless ASCII characters just aren't enough to capture the full intentions and feelings of the human being behind them. When you find yourself sending kilobytes of ASCII back and forth, and still are unsatisfied that you're communicating, you should instill a reflexive habit of "going voice" on your team.

Never underestimate the power of actually talking to another human being. I know, I know, the whole reason we got into this programming thing was to avoid talking to other people, but bear with me here. You can't be face to face on a remote team without flying 6 plus hours, and who the heck has that kind of time? I've got work I need to get done! Well, the next best thing to hopping on a plane is to fire up Skype and have a little voice chat. Easy peasy. All that human nuance which is totally lost in faceless ASCII characters (yes, even with our old pal

*<:-)) will come roaring back if you regularly schedule voice chats. I recommend at least once a week at an absolute minimum; they don't have to be long meetings, but it sure helps in understanding the human being behind all those awesome checkins.

Nobody hates meetings and process claptrap more than I do, but there is a certain amount of process you'll need to keep a bunch of loosely connected remote teams and developers in sync.

- Monday team status reports

Every Monday, as in somebody's-got-a-case-of-the, each team should produce a brief, summarized rundown of:

- What we did last week

- What we're planning to do this week

- Anything that is blocking us or we are concerned about

This doesn't have to be (and in fact shouldn't be) a long report. The briefer the better, but do try to capture all the useful highlights. Mail this to the mailing list every Monday like clockwork. Now, how many "teams" you have is up to you; I don't think this needs to be done at the individual developer level, but you could.

-

Meeting minutes

Any time you conduct what you would consider to be a "meeting" with someone else, take minutes! That is, write down what happened in bullet point form, so those remote team members who couldn't be there can benefit from – or at least hear about – whatever happened.

Again, this doesn't have to be long, and if you find taking meeting minutes onerous then you're probably doing it wrong. A simple bulleted list of sentences should suffice. We don't need to know every little detail, just the big picture stuff: who was there? What topics were discussed? What decisions were made? What are the next steps?

Both of the above should, of course, be mailed out to the mailing list as they are completed so everyone can be notified. You do have a mailing list, right? Of course you do!

If this seems like a lot of jibba-jabba, well, that's because remote development is hard. It takes discipline to make it all work, certainly more discipline than piling a bunch of programmers into the same cubicle farm. But when you imagine what this kind of intellectual work – not just programming, but anything where you're working in mostly thought-stuff – will be like in ten, twenty, even thirty years … don't you think it will look a lot like what happens every day right now on Stack Overflow? That is, a programmer in Brazil helping a programmer in New Jersey solve a problem?

If I have learned anything from Stack Overflow it is that the world of programming is truly global. I am honored to meet these brilliant programmers from every corner of the world, even if only in a small way through a website. Nothing is more exciting for me than the prospect of adding international members to the Stack Overflow team. The development of Stack Overflow should be reflective of what Stack Overflow is: an international effort of like-minded – and dare I say totally awesome – programmers. I wish I could hire each and every one of you. OK, maybe I'm a little biased. But to me, that's how awesome the Stack Overflow community is.

I believe remote development represents the future of work. If we have to spend a little time figuring out how this stuff works, and maybe even make some mistakes along the way, it's worth it. As far as I'm concerned, the future is now. Why wait?