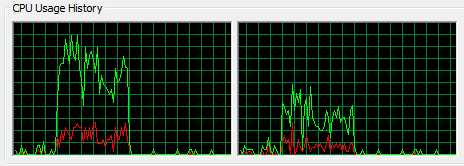

multicore programming

Re-Encoding Your DVDs

Like Donald Knuth, I think much of the current multicore hype is overrated. The machine I use today has dual processors. I get to use them both only when I’m running two independent jobs at the same time; that’s nice, but it happens only a few minutes every