One thing that continually frustrates me when working with dedicated test teams is that, well, they find too many bugs.

One thing that continually frustrates me when working with dedicated test teams is that, well, they find too many bugs.

Don't get me wrong. I want to be the first person to know about any bug that results in inconvenience for a user. But how do you distinguish between bugs that users are likely to encounter, and bugs that users will probably never see?

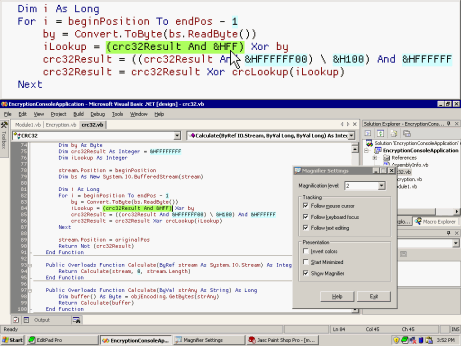

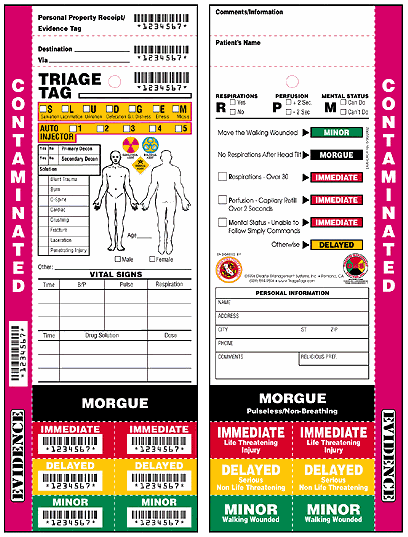

The first thing you do is take that list of bugs from the testers and have yourself a triage meeting:

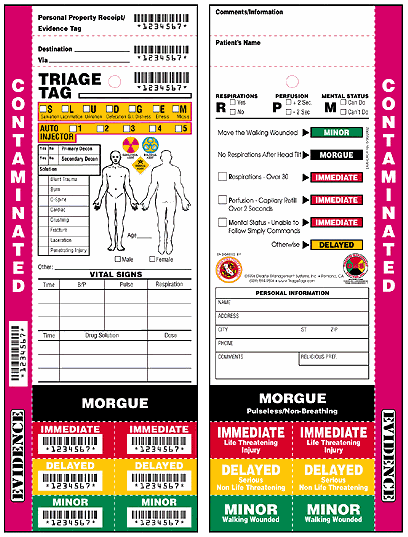

The term "triage" was borrowed from medical triage where a doctor or nurse has to prioritize care for a large group of injured people. The main job of a software bug triage team is to decide which bugs need to be fixed (or conversely, which bugs we're willing to ship with).

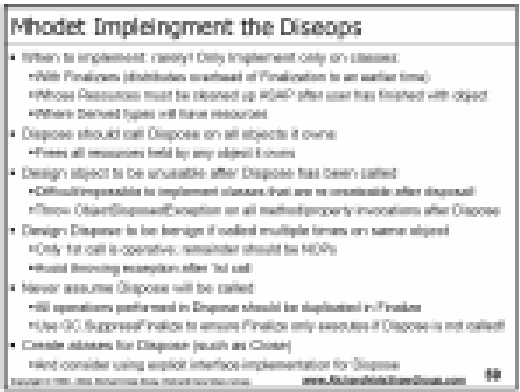

Eric lists four questions that need to be answered during triage to decide whether a bug should be fixed or not:

- Severity: When this bug happens, how bad is the impact?

- Frequency: How often does this bug happen?

- Cost: How much effort would be required to fix this bug?

- Risk: What is the risk of fixing this bug?

Triage isn't exactly my idea of a good time. But you have to do it, because you'll always have far more bugs than you have development time. Nobody has the luxury of fixing all the bugs in their software.

Testers produce two kinds of bugs:

- A small subset of very serious bugs that everyone can immediately agree on. These are great. They're the kind of catches that make me thank my lucky stars that we have dedicated testers. You go, girl-slash-boy!

- Everything else. A vast, gray wasteland of pseudo-bugs that nobody can really agree on. Is it an inconvenience for the user? Would users really do things this way? Would a user ever run into this? Do we even care?

It's a clear win for the bugs everyone agrees on. That's usually about ten to twenty percent of the bug list in my experience. But for everything else, there's a serious problem: testers aren't real users. I'd give a bug from a customer ten times the weight of a bug reported by a tester.

The source of the bug is just one factor to consider. Bug triage isn't a science. It's highly subjective and totally dependent on the specifics of your application. In Bugs Are a Business Decision, Jan Goyvaerts describes how different triage can be for applications at each end of that spectrum:

Last July I flew to Denver to attend the Shareware Industry Conference. I flew the leg from Taipei to Los Angeles on a Boeing 747 operated by China Airlines. This aircraft has two major software systems on board: the avionics software (flight computer), and the in-flight entertainment system. These two systems are completely independent of each other, developed by different companies, to different standards.

The avionics software is the software that flies the plane. No, the pilots don't fly the plane, the flight computer does. How many bugs would you tolerate in the avionics software? How many do you think Boeing left unfixed? How many people have ever been killed by software bugs in modern airliners? Zero. A flawed flight computer would immediately ground all 747s worldwide. Boeing would not recover.

The in-flight entertainment system is a completely different story. It's not essential to the plane. It only serves to make the passengers forget how uncomfortable those economy seats really are. If the entertainment system barfs all over itself, the cost is minimal. Passengers are already out of their money, and most will choose their next flight based on price and schedule rather than which movies are on those tiny screens, if any. I was actually quite pleased with Chine Airlines' system, which offered economy passengers individual screens and a choice of a dozen or so on-demand movies (i.e. each passenger can start viewing any movie at any time, and even pause and rewind). That is, until the system started acting up. It locked up a few times causing everybody's movie to pause for several minutes. Once, the crew had to reboot the whole thing. That silly Linux penguin mocked me for several minutes while the boot messages crept by. X11 showed off its X-shaped cursor right in the middle of the screen even longer. Judging from the crew's attitude about it, the reboot seemed like something that's part of their training.

Bugs also cost money to fix. In My Life as a Code Economist, Eric Sink outlines all the decisions that go into whether or not a bug gets fixed at his company:

Don't we all start out with the belief that software only gets better as we work on it? The fact that we need regression testing is somehow like evidence that there is something wrong with the world. After all, it's not like anybody on our team is intentionally creating new bugs. We're just trying to make sure our product gets better every day, and yet, somewhere between 3.1.2 and 3.1.3, we made it worse.

But that's just the way it is. Every code change is a risk. A development cycle that doesn't recognize this will churn indefinitely and never create a shippable product. At some point, if the product is ever going to converge toward a release, you have to start deciding which bugs aren't going to get fixed.

To put it another way, think about what you want to say to yourself when look in the mirror just after your product is released. The people in group 2 want to look in the mirror and say this:

"Our bug database has ZERO open items. We didn't defer a single bug. We fixed them all. After every bug fix, we regression tested the entire product, with 100% code coverage. Our product is perfect, absolutely flawless and above any criticism whatsoever."

The group 1 person wants to look in the mirror and say this:

"Our bug database has lots of open items. We have carefully reviewed every one of them and consider each one to be acceptable. In other words, most of them should probably not even be called bugs. We are not ashamed of this list of open items. On the contrary, we draw confidence from this list because we are shipping a product with a quality level that is well known. There will be no surprises and no mulligans. We admit that our product would be even better if all of these items were "fixed", but fixing them would risk introducing new bugs. We would essentially be exchanging these bugs which we find acceptable for the possibility of newly introduced bugs which might be showstoppers."

I'm not talking about shipping crappy products. I'm not suggesting that anybody ship products of low quality. I'm suggesting that decisions about software quality can be tough and subtle, and we need to be really smart about how to make those decisions. Sometimes a "bug" should not be fixed.

To me, triage is about one thing: making life better for your users. And the best way to do that is to base your triage decisions on data from actual usage -- via exception reporting, user feedback, and beta testing. Otherwise, triage is just a bunch of developers and testers in a room, trying to guess what users might do.

Discussion

One thing that continually frustrates me when working with dedicated test teams is that, well, they find too many bugs.

One thing that continually frustrates me when working with dedicated test teams is that, well, they find too many bugs.