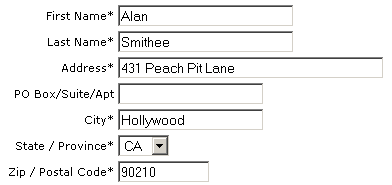

Jon Galloway called me out in a comment yesterday for advocating a non-standard approach:

Web forms have become a convention, and users have been trained for 10 years on how to fill out forms. Users would get confused, and some would bail out (abandon carts, etc.). Web forms work, and we know how to use them. Your form example violates the "Don't Make Me Think" principle on many levels.

In a sense, he's right. When it comes to coding, as Steve Rowe points out, always favor consistency over cleverness:

The class isn't the main point of this post, however. Rather, it is some advice that Peter gave a few times during the class. Someone might ask a question like "Can't I do x in some funky way?" and he would answer, "You could, but no one would expect to see it so don't." The point he was making is that we, as programmers, should stay away from being clever. We should, as much as possible, try to do things the same way everyone else does them. Why? Because you won't be the only person to work on this code. Even if you are, the next time you touch it might be a year or two from now. If you did something clever, the next person to touch it will look at the code and not immediately understand. This will have one of two consequences. Either they will have to spend 10 minutes just trying to understand what it is you did or, worse, they will assume you made a mistake and "fix" it by making it less clever. Neither of these results is desireable. Unless you are writing one-off code for yourself you need to write it in a manner to make it easily understandable so that it can be easily maintained.

It's clearly a bad idea to write code with a "how 'bout we try it this way" mentality, as humorously noted by Alex Papadimoulis:

"A client has asked me to build and install a custom shelving system. I'm at the point where I need to nail it, but I'm not sure what to use to pound the nails in. Should I use an old shoe or a glass bottle?"

a) It depends. If you are looking to pound a small (20lb) nail in something like drywall, you'll find it much easier to use the bottle, especially if the shoe is dirty. However, if you are trying to drive a heavy nail into some wood, go with the shoe: the bottle with shatter in your hand.

b) There is something fundamentally wrong with the way you are building; you need to use real tools. Yes, it may involve a trip to the toolbox (or even to the hardware store), but doing it the right way is going to save a lot of time, money, and aggravation through the lifecycle of your product. You need to stop building things for money until you understand the basics of construction.

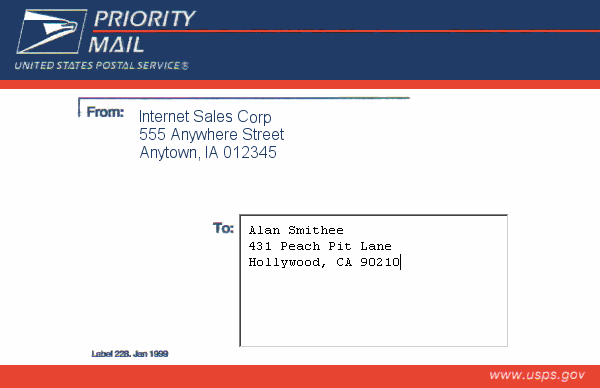

However, when it comes to issues of user interface, consistency isn't always a virtue. User interfaces should be internally consistent, but not necessarily consistent with every other application in the rest of the world. That said, some UI elements become so ingrained into popular culture that they should be followed for consistency's sake. Some good examples are:

- A search box in the upper-right hand corner

- A logo in the upper-left hand corner that takes you back home

- The "forward" and "back" buttons

But not all user interface conventions are created equal. Some are timeless. Some are there by default, because nobody bothered to sufficiently question them. Some grow old and outlive their usefulness. How do we discriminate between conventions that actually help us and those that are merely.. expected?

The answer, of course, is to try multiple approaches and collect usage data to determine what works and what doesn't. This is (relatively) easy for web apps, which is why Amazon, Yahoo and Google are all notorious for doing it. They'll serve up experimental features to a tiny fraction of the user base, collect data on how those features are used, then feed that back into their decision making process.

If we built UI with an iron-clad guarantee that we would "do it like everyone else", would we have ever experienced the ultra simple Mom-friendly Tivo UI? Or Windows Media Center's amazing, utterly un-Windows-like ten foot UI? Would Office 12 be using the innovative new ribbon instead of traditional toolbars and menus? Heck, would we have ever made the transition from character mode to GUIs?

I think UI experimentation is not only desirable, but necessary. If we don't experiment, we can't evolve UI forward. However, you have to do it the right way:

- Have a complete understanding of the current convention and how it arose

- Have a good, reasoned argument for deviating from the convention

- Collect usage data on your experiments

- Make decisions based on the usage data

If you're not collecting usage data, or your reason is "it looks better this way", then you're doing it wrong, and you should stick with the conventions.

Discussion

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()