unix

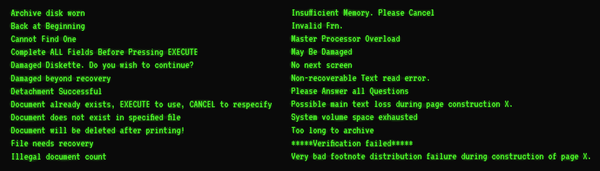

UNIX will never be usable

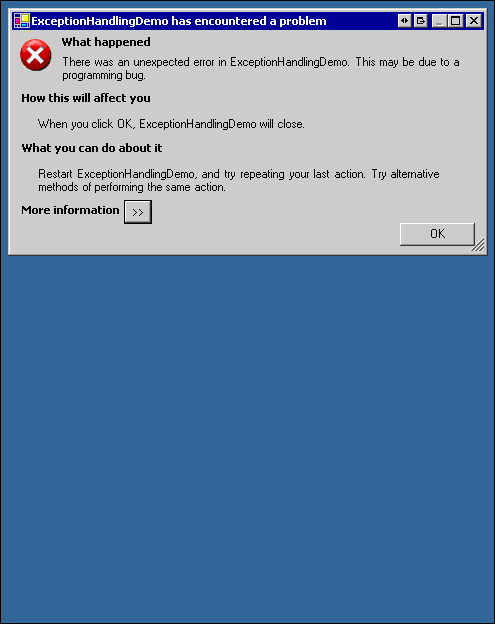

A few months ago, Eric Raymond, the open source guru best known for his seminal paper, The Cathedral and the Bazaar, posted a rant about the difficulty he encountered with a common user printing scenario in UNIX. The follow-up post is even more intriguing: I am informed that an RFE