You’re Probably Storing Passwords Incorrectly

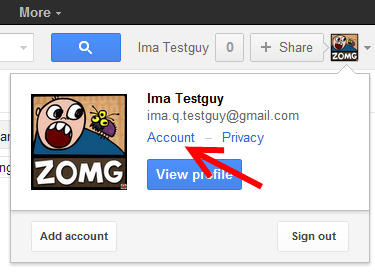

The web is nothing if not a maze of user accounts and logins. Almost everywhere you go on the web requires yet another new set of credentials. Unified login seems to elude us at the moment, so the status quo is an explosion of usernames and passwords for every user. As a consequence of all this siloed user identity data, Facebook and most other web apps encourage us to give out our credentials like Halloween candy, as Dare Obasanjo notes:

On Facebook, there is an option to import contacts from Yahoo! Mail, Hotmail, AOL and Gmail which requires me to enter my username and password from these services into their site. Every time I login to Yahoo! Mail there is a notice that asks me to import my contacts from other email services which requires me to give them my credentials from these services as well.

This is a deplorable state of affairs. We’re teaching users that their credentials are of little value and should be freely handed out to any passing website that catches their fancy. It’s an incredibly dangerous habit to inculcate in users; it makes them far more vulnerable to phishing:

If users get comfortable with entering their credentials in all sorts of random places then it makes them more susceptible to phishing attacks. This is one of the reasons services like Meebo are worrying to me.

The last thing we should be doing is coming up with ways to make phishing more powerful. Phishing is a social engineering exploit so timeless, so effective, and so powerful, I call it the forever hack. Rainbow table and brute force attacks can be defeated through judicious use of technology. Phishing can’t.

Users collect usernames and passwords like they do Pokémon. It’s a sorry state of affairs, but for better or worse, that’s the way it is. We, as software developers, are trusted with storing all these usernames and passwords in some sort of database. The minute we store a user’s password, we’ve taken on the responsibility of securing their password, too. Let’s say a hacker somehow obtains a list of all our usernames and passwords. Either it was an inside job by someone who had access to the database, or the database was accidentally exposed to the public web. Doesn’t matter how. It just happened.

Even if hackers have our username and password table, we’re covered, right? All they’ll see is the hash values. Only the most grossly incompetent of developers would actually store passwords as plaintext in the database, right? Right?

Recently, the folks behind Reddit.com confessed that a backup copy of their database had been stolen. Later, spez, one of the Reddit developers, confirmed that the database contained password information for Reddit’s users, and that the information was stored as plain, unprotected text. In other words, once the thief had the database, he had everyone’s passwords as well.

Wrong.

I’m only a mouth-breathing Windows developer, not one of the elite Y-combinating Lisp, oops, Python developers working on Reddit. And even I know better than that.

You might think it’s relatively unimportant if someone’s forum password is exposed as plain text. After all, what’s an attacker going to do with crappy forum credentials? Post angry messages on the user’s behalf? But most users tend to re-use the same passwords, probably because they can’t remember the two dozen unique usernames and passwords they’re forced to have. So if you obtain their forum password, it’s likely you also have the password to something a lot more dangerous: their online banking and PayPal.

My point here is not to drag the good names of the developers at Reddit through the mud. We’re all guilty. I’m sure every developer reading this has stored passwords as plain text at some point in their career. I know I have. Forget the blame. The important thing is to teach our peers that storing plaintext passwords in the database is strictly forbidden – that there’s a better way, starting with basic hashes.

Hashing the passwords prevents plaintext exposure, but it also means you’ll be vulnerable to the astonishingly effective rainbow table attack I documented last week. Hashes alone are better than plain text, but barely. It’s not enough to thwart a determined attacker. Fortunately, the kryptonite for rainbow table attacks is simple enough – add a salt value to the hashes to make them unique. I provided an example of a salted hash in my original post:

hash = md5(‘deliciously-salty-’ + password)

But IANAC – I Am Not A Cryptographer. I meant this only as an example, not as production code that you should copy and paste into that hugely popular enterprise banking solution you’re working on. In fact, I ripped it almost directly from Rich Skrenta’s excellent post on using MD5 hashes as utility functions.

Thomas Ptacek, on the other hand, is a cryptographer, and he has a bone to pick with my choice of salting techniques.

What have we learned? We learned that if it’s 1975, you can set the ARPANet on fire with rainbow table attacks. If it’s 2007, and rainbow table attacks set you on fire, we learned that you should go back to 1975 and wait 30 years before trying to design a password hashing scheme.*

We learned that if we had learned anything from this blog post, we should be consulting our friends and neighbors in the security field for help with our password schemes, because nobody is going to find the game-over bugs in our MD5 schemes until after my Mom’s credit card number is being traded out of a curbside stall in Tallinn, Estonia.

We learned that in a password hashing scheme, speed is the enemy. We learned that MD5 was designed for speed. So, we learned that MD5 is the enemy. Also Jeff Atwood and Richard Skrenta.

Finally, we learned that if we want to store passwords securely we have three reasonable options: PHK’s MD5 scheme, Provos-Maziere’s Bcrypt scheme, and SRP. We learned that the correct choice is Bcrypt.

*Editor’s note: Not quite true. Most “modern” software does not use a modern password scheme. Windows XP/2000/NT, phpBB, the majority of custom password schemes; all vulnerable to rainbow table precomputation attacks.

In summary, if we’re storing passwords, we’re probably storing those passwords incorrectly. If it isn’t obvious by now, cryptography is hard, and the odds of us getting it right on our own are basically nil. That’s why we should rely on existing frameworks, and the advice of experts like Thomas. What higher praise is there than that of praise from your sworn enemy?

Let’s recap:

- Do not invent your own “clever” password storage scheme. I know, you’re smart, and you grok this crypto stuff. But through this door lies madness – and abominations like LMHash that have ongoing, worldwide security ramifications we’re still dealing with today. Take advantage of whatever password storage tools your framework provides, as they’re likely to be a heck of a lot better tested and more battle-proven than any crazy scheme you and your team can come up with on your own. Security vulnerabilities, unlike functionality bugs in your application, run deep and silent. They can lay dormant for years.

- Never store passwords as plaintext. This feels like security 101 and is completely obvious in retrospect. But not everyone knows what you know – just ask Reddit. Store the hashes, never the actual passwords. Educate your fellow developers.

- Add a long, unique random salt to each password you store. The point of a salt (or nonce, if you prefer) is to make each password unique and long enough that brute force attacks are a waste of time. So, the user’s password, instead of being stored as the hash of “myspace1,” ends up being stored as the hash of 128 characters of random unicode string + “myspace1.” You’re now completely immune to rainbow table attack.

- Use a cryptographically secure hash. I think Thomas hates MD5 so very much it makes him seem a little crazier than he actually is. But he’s right. MD5 is vulnerable. Why pick anything remotely vulnerable, when you don’t have to? SHA-2 or Bcrypt would be a better choice.

Of course, none of this guarantees you’ll be able to prevent someone from deducing that Joe User’s Myspace account password is “myspace1.”

But when they do, at least it won’t be your fault.