We Done Been... Framed!

In my previous post, Url Shorteners: Destroying the Web Since 2002, I mentioned that one of the “features” of the new generation of URL shortening services is to frame the target content.

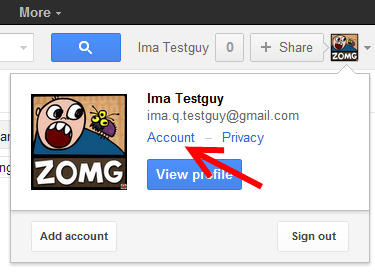

Digg is one of the most popular sites to implement this strategy. Here’s how it works. If you’re logged in to Digg, every target link you click from Digg is a shortened URL of their own creation. If I click through to a Stack Overflow article someone else has “Dugg,” I’m sent to this link.

For logged in users, every outgoing Digg link is framed inside the “DiggBar.” It’s a way of dragging the Digg experience with you wherever you go – while you’re reading the target article, you can vote it up, see related articles, share, and so forth. And if you share this shortened URL with other users, they’ll get the same behavior, provided they also hold a Digg login cookie.

At this point you’re probably expecting me to rant about how evil the DiggBar is, and how it, too, is destroying the web, etcetera, etcetera, so on, and so forth. But I can’t muster the indignant rage. I can give you, at best, ambivalence. Here’s why:

- The DiggBar is not served to the vast majority of anonymous users, but only to users who have opted in to the Digg experience by signing up.

- The new rel =“canonical” directive is used on target links so search engines can tell which links are the “real”, authoritative links to the content. They won’t be confused or have search engine juice diluted by Digg’s shortened URLs. At least that’s the theory, anyway.

- No Digg ads are served via the DiggBar, so the framed content is not “wrapped” in ads.

- I believe Digg users themselves can opt out of DiggBar via a preferences setting.

Digg is trying to build a business, just like we are with Stack Overflow. I can’t fault them for their desire to extend the Digg community outward a little bit, given the zillions of outgoing links they feed to the world. Particularly when they attempted to do so in a semi-ethical way, actively soliciting community feedback along the way.

In short, Digg isn’t the problem. But even if they were – if you don’t want to be framed by the DiggBar, or any other website for that matter, you could put so-called “frame-busting” JavaScript in your pages.

if (parent.frames.length > 0) {

top.location.replace(document.location);

}

Problem solved! This code (or the many frame-busting variants thereof) does work on the DiggBar. But not every framing site is as reputable as Digg. What happens when we put on our hypothetical black hats and start designing for evil?

I’ll tell you what happens. This happens.

var prevent_bust = 0 window.onbeforeunload = function() { prevent_bust++ } setInterval(function() { if (prevent_bust > 0) { prevent_bust -= 2 window.top.location = ‘http://server-which-responds-with-204.com’ } }, 1)On most browsers a 204 (No Content) HTTP response will do nothing, meaning it will leave you on the current page. But the request attempt will override the previous frame busting attempt, rendering it useless. If the server responds quickly this will be almost invisible to the user.

When life serves you lemons, make a lemon cannon. Produce frame-busting-busting JavaScript. This code does the following:

- increments a counter every time the browser attempts to navigate away from the current page, via the

window.onbeforeonloadevent handler - sets up a timer that fires every millisecond via

setInterval(), and if it sees the counter incremented, changes the current location to an URL of the attacker’s control - that URL serves up a page with HTTP status code 204, which does not cause the browser to navigate anywhere

Net effect: frame-busting busted. Which might naturally lead you to wonder – hey buster, can you bust the frame-busting buster? And, if so, where does it end?

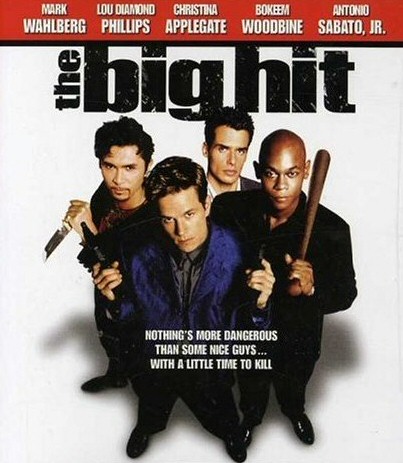

In the 1998 movie, The Big Hit, the protagonists kidnap the daughter of an extremely wealthy Japanese businessman. When they call to deliver the ransom notice, they turn to Gump who employs a brand name Trace Buster to prevent police from tracing the call.

Unbeknownst to Gump, the father has a Trace-Buster-Buster at his disposal. This in turn triggers Gump to use his Trace-Buster-Buster-Buster in an ever escalating battle to evade detection.

What’s really scary is that near as I can tell, there is no solution. Due to cross-domain JavaScript security restrictions, it is almost impossible for the framed site to block or interfere with the parent page’s evil JavaScript that is intentionally and aggressively blocking the framebusting.

If an evil website decides it’s going to frame your website, you will be framed. Period. Frame-busting is nothing more than a false sense of security; it doesn’t work. This was a disturbing revelation to me, because framing is the first step on the road to clickjacking:

A clickjacked page tricks a user into performing undesired actions by clicking on a concealed link. On a clickjacked page, the attackers show a set of dummy buttons, then load another page over it in a transparent layer. The users think that they are clicking the visible buttons, while they are actually performing actions on the hidden page. The hidden page may be an authentic page, and therefore the attackers can trick users into performing actions which the users never intended to do and there is no way of tracing such actions later, as the user was genuinely authenticated on the other page.

For example, a user might play a game in which they have to click on some buttons, but another authentic page like a web mail site from a popular service is loaded in a hidden iframe on top of the game. The iframe will load only if the user has saved the password for its respective site. The buttons in the game are placed such that their positions coincide exactly with the select all mail button and then the delete mail button. The consequence is that the user unknowingly deleted all the mail in their folder while playing a simple game. Other known exploits have been tricking users to enable their webcam and microphone through flash (which has since been corrected by Adobe), tricking users to make their social networking profile information public, making users follow someone on Twitter, etc.

I’ve fallen prey to a mild clickjacking exploit on Twitter myself! It really does happen – and it’s not hard to do.

Yes, Digg frames ethically, so your frame-busting of the DiggBar will appear to work. But if the framing site is evil, good luck. When faced with a determined, skilled adversary that wants to frame your content, all bets are off. I don’t think it’s possible to escape. So consider this a wakeup call: you should build clickjacking countermeasures as if your website could be framed at any time.

I was a skeptic. I didn’t want to believe it either. But once shown the exploits on our own site – fortunately, by a white hat security expert – I lived to regret that. Don’t let frame-busting code lull you into a false sense of security, too.