Extending Your Wireless Network With Better Antennas

When I set up my new Xbox 360, I also connected it to my existing wireless network. It’s about 50 feet from my access point, with approximately 4 or 5 walls in between. I was able to get online, but barely. The signal strength indicator was at literally one bar of strength, and the signal graph was about close as you can get to no connection while still having a connection. That marginal WiFi connection was enough to get me to Xbox Live. But I also wanted to take advantage of the impressive Xbox 360 media extender functionality – to connect to my existing Vista Media Center home theater PC to listen to music or watch videos. That definitely requires a better wireless connection.

I’ve already positioned everything as optimally as I can; the only thing I could think of to improve the signal even further was to upgrade to better, more powerful antennas. Note that my Xbox is in an outside room that is not physically connected to the house, so a wired connection isn’t practical.

I did some web searching, and I found that wireless networking feels more like an art than a science. There are just so many variables:

- the physical layout of your equipment

- the environment

- interference from other wireless networks

- the firmware and configuration of your networking hardware

… and so on. It’s almost impossible to tell if an antenna will work until you buy it and run network strength tests in your particular environment.

There are a few recurring themes, though. One is the “cantenna”; there are many variations of this design on the market.

As you can see from the picture, the “can” in the name refers to the fact that these antennas can be built with the exact same kinds of cans you’d find at your local grocery store. This one looks like a Pringles potato chip can, and it’s a very popular style. Lots of smaller vendors sell variations of this design. Reviews of the archetypal cantenna design show good results, but it is highly directional – you have to point it at the target, and it’s only truly effective in that direction.

Part of the appeal of the cantenna is that you can build them quite easily yourself. This comprehensive homebrew antenna comparison showed that self-built cantennas can perform extremely well, if you follow waveguide theory when you build them:

The results surprised me! In our test, the Flickenger Pringles can did a little better than my modified Pringles design. Both did no better than the Lucent omnidirectional. Now this is just on raw signal strength, noise rejection due to directivity still makes a directional antenna a better choice for some uses even if there is no gain benefit. The waveguides all soundly trounced the Pringles can designs. I mean they stomped them into the ground on signal strength – as much as 9 dB better. Every three dB is a doubling in power – that’s three doublings (8x increase)!

With these results, I’m convinced that the waveguide design is the way to go for cheap wireless networking. The performance is good, the cost is very low and the skill required is minimal. If you can eat a big can of stew, you can make a high performance antenna.

If you’re interested in constructing a waveguide cantenna, I found this excellent detailed guide, with lots of step by step photos, a JavaScript size calculator, and recommended off the shelf cans you can buy to start with.

There are, of course, any number of commercial aftermarket WiFi antennas to choose from, too. If you’re interested in upgrading, first make sure your router has a removable antenna.

Next, determine what kind of connector the antenna uses on your router. There’s an excellent wireless antenna connector visual guide here; the RP-SMA and RP-TNC connectors are common, but it does vary. You’ll want to make sure you have the right connector “pigtail” cable for whatever antenna you buy, unless it happens to use the same native connector type. My router uses a RP-SMA connector.

After you’ve gathered this essential information, your goal is to replace your generic, stock – dare I say wimpy – router antenna with something better.

There are lots of aftermarket upgrade antennas to choose from, but I am a sucker for Hawking models. I’ve used their portable Hi-Gain Wireless USB adapter for years; its compact folding directional antenna is a marvel at picking out signal from the noise. They have a lot of antenna designs to choose from; let’s compare:

HAI6SIP | 6 dBi | 3" x 3" x 11.6" | $32 |

HAI7SIP | 7 dBi | 3.4" x 3.4" x 8.9" | $40 |

HAI7MD | 7 dBi | 2.8" x 2.8" x 6.1" | $38 |

HAI8DD | 8 dBi | 5" x 5" x 5" | $50 |

HAI15SC | 15 dBi | 2" x 3.9" x 8.6" | $45 |

HAO14SDP | 14 dBi | 1" x 3" x 9" | $83 |

This is only a brief summary of the most likely indoor antenna models; Hawking has a bunch more antennas to choose from on their web site. Be careful, because customer reviews are all over the map on these things, which says more about the immense number of variables in wireless networking than it does about the antennas themselves. I chose to go with the HAI7MD model, which I thought had a nice blend of some directionality, compact size, and performance/price. I also like that it can be detached from its little stand and connected directly to the router in lieu of the stock antenna, if you don’t need the positioning flexibility the stand provides.

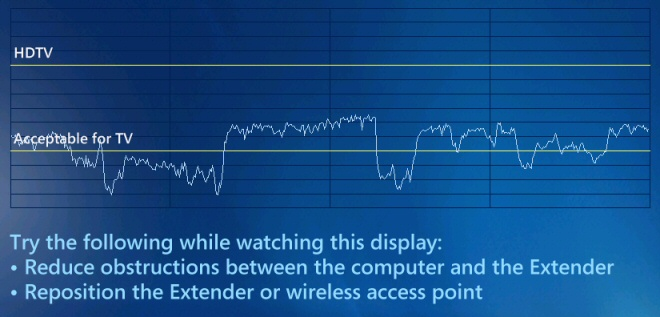

Here are my results from the media extender network test. The test is a bit variable because I’m experimenting with the antenna positioning to see what produces the strongest connection.

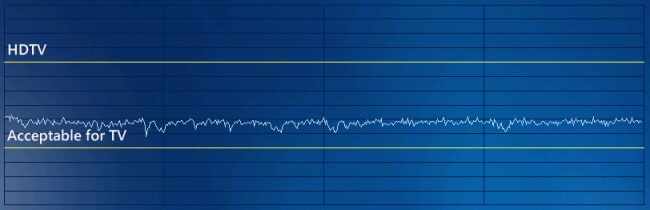

Before I added this antenna, that white line would have been just above the bottom-most black line on the graph. That’s how bad it was. Upgrading my antenna increased my wireless networking connection strength by about 5x. Here’s the final result as shown in the Media Center extender network performance monitor test screen:

As fantastic as this improvement is, now I’m tempted to go back and buy that really huge HAI15SC corner antenna to see how much better it can get. At any rate, if you’re looking to improve your wireless network performance, definitely consider aftermarket antenna upgrades. In my experience, a better antenna can make the difference between a completely marginal connection and a rock solid connection.