The “Just In Time” Theory of User Behavior

I’ve long believed that the design of your software has a profound impact on how users behave within your software. But there are two sides to this story:

- Encouraging the “right” things by making those things intentionally easy to do.

- Discouraging the “wrong” things by making those things intentionally difficult, complex, and awkward to do.

Whether the software is doing this intentionally, or completely accidentally, it’s a fact of life: the path of least resistance is everyone’s best friend. Learn to master this path, or others will master it for you.

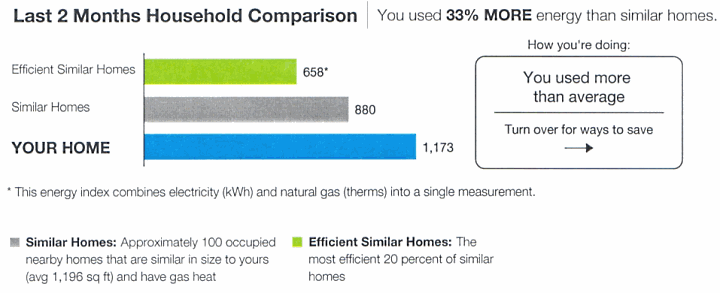

For proof, consider Dan Ariely’s new and amazing book, The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves.

Indeed, let’s be honest: we all lie, all the time. Not because we’re bad people, mind you, but because we have to regularly lie to ourselves as a survival mechanism. You think we should be completely honest all the time? Yeah. Good luck with that.

But these healthy little white lies we learn to tell ourselves have a darker side. Have you ever heard this old adage?

One day, Peter locked himself out of his house. After a spell, the locksmith pulled up in his truck and picked the lock in about a minute.

“I was amazed at how quickly and easily this guy was able to open the door,” Peter said. The locksmith told him that locks are on doors only to keep honest people honest. One percent of people will always be honest and never steal. Another 1% will always be dishonest and always try to pick your lock and steal your television; locks won’t do much to protect you from the hardened thieves, who can get into your house if they really want to.

The purpose of locks, the locksmith said, is to protect you from the 98% of mostly honest people who might be tempted to try your door if it had no lock.

I had heard this expressed less optimistically before as

10% of people will never steal, 10% of people will always steal, and for everyone else… it depends.

The “it depends” part is crucial to understanding human nature, and that’s what Ariely spends most of the book examining in various tests. If for most people, honesty depends, what exactly does it depend on? The experiments Ariely conducts prove again and again that most people will consistently and reliably cheat “just a little,” to the extent that they can still consider themselves honest people. The gating factor isn’t laws, penalties, or ethics. Surprisingly, that stuff has virtually no effect on behavior. What does, though, is whether they can personally still feel like they are honest people.

This is because they don’t even consider it cheating – they’re just taking a little extra, giving themselves a tiny break, enjoying a minor boost, because well, haven’t they been working extra specially hard lately and earned it? Don’t they of all people deserve something nice once in a while, and who would even miss this tiny amount? There’s so much!

These little white lies are the path of least resistance. They are everywhere. If laws don’t work, if ethics classes don’t work, if severe penalties don’t work, how do you encourage people to behave in a way that “feels” honest that is actually, you know, honest? Feelings are some pretty squishy stuff.

It’s easier than you think.

My colleagues and I ran an experiment at the University of California, Los Angeles. We took a group of 450 participants, split them into two groups and set them loose on our usual matrix task. We asked half of them to recall the Ten Commandments and the other half to recall 10 books that they had read in high school.

Among the group who recalled the 10 books, we saw the typical widespread but moderate cheating. But in the group that was asked to recall the Ten Commandments, we observed no cheating whatsoever. We reran the experiment, reminding students of their schools’ honor codes instead of the Ten Commandments, and we got the same result. We even reran the experiment on a group of self-declared atheists, asking them to swear on a Bible, and got the same no-cheating results yet again.

That’s the good news: a simple reminder at the time of the temptation is usually all it takes for people to suddenly “remember” their honesty.

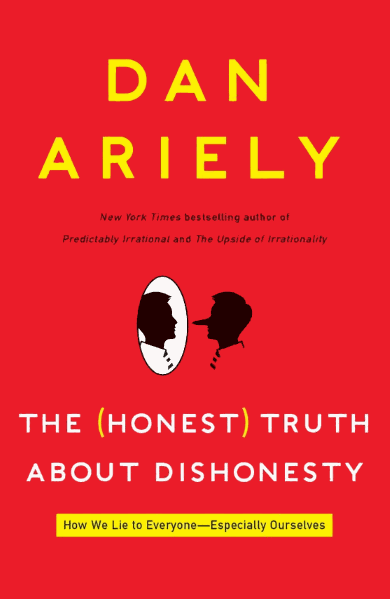

The bad news is Clippy was right.

In my experience, nobody reads manuals, nobody reads FAQs, and nobody reads tutorials. I am exaggerating a little here for effect, of course. Some A+ students will go out of their way to read these things. That’s how they became A+ students, by naturally going the extra mile, and generally being the kind of users who teach themselves perfectly well without needing special resources to get there. When I say “nobody” I mean the vast overwhelming massive majority of people you would really, really want to read things like that. People who don’t have the time or inclination to expend any effort at all other than the absolute minimum required, people who are most definitely not going to go the extra mile.

In other words, the whole world.

So how do you help people who, like us, just never seem to have the time to figure this stuff out because they’re, like, suuuuper busy and stuff?

You do it by showing them…

- the minimum helpful reminder

- at exactly the right time

This is what I’ve called the “Just In Time” theory of user behavior for years. Sure, FAQs and tutorials and help centers are great and all, but who has the time for that? We’re all perpetual intermediates here, at best.

The closer you can get your software to practical, useful “Just In Time” reminders, the better you can help the users who are most in need. Not the A+ students who already read the FAQ, and studied the help center intently, but those users who never read anything. And now, thanks to Dan Ariely, I have the science to back this up. Even something as simple as putting your name on the top of a form to report auto insurance millage, rather than the bottom, resulted in a mysterious 10% increase in average miles reported. Having that little reminder right at the start that hey, your name is here on this form, inspired additional honesty. It works.

Did we use this technique on Stack Overflow and Stack Exchange? Indeed we did. Do I use this technique on Discourse? You bet, in even more places, because this is social discussion, not technical Q&A. We are rather big on civility, so we like to remind people when they post on Discourse they aren’t talking to a computer or a robot, but a real person, a lot like you.

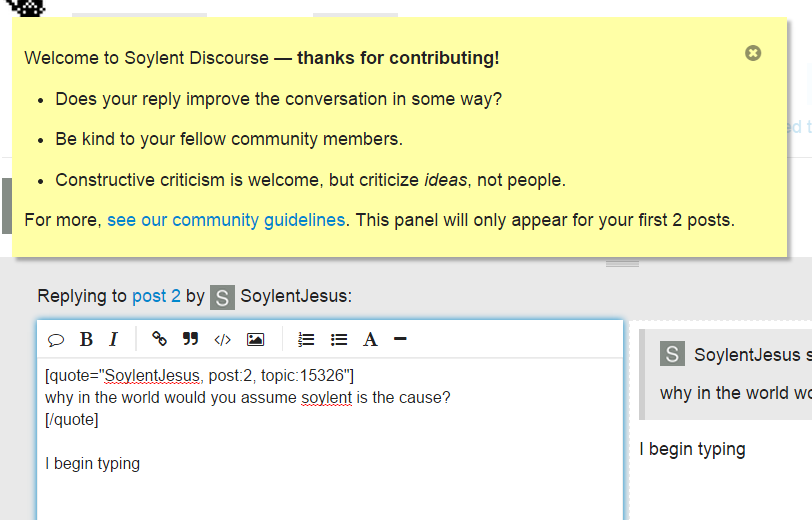

When’s the natural time to remind someone of this? Not when they sign up, not when they’re reading, but at the very moment they begin typing their first words in their first post. This is the moment of temptation when you might be super mega convinced that someone is Wrong on the Internet. So we put up a gentle little reminder Just In Time, right above where they are typing:

Then hopefully, as Dan Ariely showed us with honesty, this little reminder will tap into people’s natural reserves of friendliness and civility, so cooler heads will prevail – and a few people are inspired to get along a little better than they did yesterday. Just because you’re on the Internet doesn’t mean you need to be yelling at folks 24/7.

We use this same technique a bunch of other places: if you are posting a lot but haven’t set an avatar, if you are adding a new post to a particularly old conversation, if you are replying a bunch of times in the same topic, and so forth. Wherever we feel a gentle nudge might help, at the exact time the behavior is occurring.

It’s important to understand that we use these reminders in Discourse not because we believe people are dumb; quite the contrary, we use them because we believe people are smart, civil, and interesting. Turns out everyone just needs to be reminded of that once in a while for it to continue to be true.