Trust Me, I’m Lying

We reflexively instruct our children to always tell the truth. It’s even encoded into Boy Scout Law. It’s what adults do, isn’t it? But do we? Isn’t telling the truth too much and too often a bad life strategy – perhaps even dangerous? Is telling children to always tell the truth even itself the whole truth?

One of the most thought provoking articles on the topic, and one I keep returning to, year after year, is I Think You’re Fat. It’s about the Radical Honesty movement, which proposes that adults follow their own advice and always tell the truth. No matter what.

The [Radical Honesty] movement was founded by a sixty-six-year-old Virginia-based psychotherapist named Brad Blanton. He says everybody would be happier if we just stopped lying. Tell the truth, all the time. This would be radical enough – a world without fibs – but Blanton goes further. He says we should toss out the filters between our brains and our mouths. If you think it, say it. Confess to your boss your secret plans to start your own company. If you’re having fantasies about your wife’s sister, Blanton says to tell your wife and tell her sister. It’s the only path to authentic relationships. It’s the only way to smash through modernity’s soul-deadening alienation. Oversharing? No such thing.

Yes. I know. One of the most idiotic ideas ever, right up there with Vanilla Coke and giving Phil Spector a gun permit. Deceit makes our world go round. Without lies, marriages would crumble, workers would be fired, egos would be shattered, governments would collapse.

And yet… maybe there’s something to it. Especially for me. I have a lying problem. Mine aren’t big lies. They aren’t lies like “I cannot recall that crucial meeting from two months ago, Senator.” Mine are little lies. White lies. Half-truths. The kind we all tell. But I tell dozens of them every day. “Yes, let’s definitely get together soon.” “I’d love to, but I have a touch of the stomach flu.” “No, we can’t buy a toy today – the toy store is closed.” It’s bad. Maybe a couple of weeks of truth-immersion therapy would do me good.

The author, A.J. Jacobs, is a great writer who made a cottage industry out of treating himself like a guinea pig, such as attempting to become the smartest man in the world, spend a year living exactly like the Bible tells us to, and to become the fittest person on Earth. Based on the strength of this article, I bought two of his books; experiments like Radical Honesty are right up his alley.

Radical honesty itself isn’t exactly a new concept. It’s been parodied in any number of screwball Hollywood comedies such as Liar, Liar (1997) and The Invention of Lying (2009). But there’s a big difference between milking this concept for laughs and exploring it as an actual lifestyle among real human beings. Among the ideas raised in the article, which you should go read now, are:

- Telling someone that something they created is terrible: is that cruelty, because they have no talent, or is it compassion, so they can know they need to improve it?

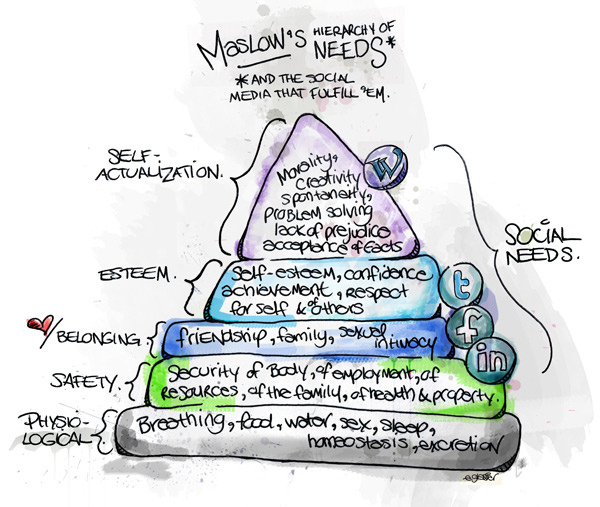

- Does a thought in your head that you never express to anyone represent your truth? Should you share it? This is particularly tricky for men, who think about sex twice as much as women.

- How much mental energy do you expend listening to a conversation trying to determine how much of what the other person is saying is untrue? Wouldn’t it be less fatiguing if everything they said was, by definition, the truth? And when you’re talking, always telling the truth means you never have to decide just how much truth to tell, how to hedge, massage, and spin the truth to make it palatable.

- In a hypothetical future when every action we take is public and broadcast to the world, is that exposing the real truth of our lives? Should we become more honest today to ready ourselves for this inevitable future?

- Always telling the truth can be thrilling, a form of risk taking, as you intentionally violate taboos around politeness that exist solely for the sake of avoiding conflict.

- Total honesty can lead to new breakthroughs in communication, where politeness prevented you from ever reaching the root, underlying causes of discontent or unhappiness.

- Honesty is more efficient. Rather than spending a lot of time sending messages back and forth artfully dancing around the truth, go directly there.

- If people see you are willing to be honest with them, they tend to return the favor, leading to a more useful relationship.

What we often don’t acknowledge is that the truth is kind of scary. That’s why we have a hard time being honest with ourselves, much less those around us. Reading through all these ambiguous situations that A.J. put himself through, you start to wonder if you understand what truth is, or what it means to decide that something is “true.” After summarizing the article in bullet form, I’m surprised there are so many points in favor of honesty, maybe even radical honesty.

But uncompromisingly committing to the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, has a darker side.

My wife tells me a story about switching operating systems on her computer. In the middle, I have to go help our son with something, then forget to come back.

“Do you want to hear the end of the story or not?” she asks.

“Well... is there a payoff?”

“F**k you.”

It would have been a lot easier to have kept my mouth closed and listened to her. It reminds me of an issue I raised with Blanton: Why make waves? “Ninety percent of the time I love my wife,” I told him. “And 10 percent of the time I hate her. Why should I hurt her feelings that 10 percent of the time? Why not just wait until that phase passes and I return to the true feeling, which is that I love her?”

Blanton’s response: “Because you’re a manipulative, lying son of a bitch.”

Rather than embrace the truth, as Radical Honesty would have us do, Adrian Tan advises us to be wary of the truth.

Most of you will end up in activities which involve communication. To those of you I have a second message: be wary of the truth. I’m not asking you to speak it, or write it, for there are times when it is dangerous or impossible to do those things. The truth has a great capacity to offend and injure, and you will find that the closer you are to someone, the more care you must take to disguise or even conceal the truth. Often, there is great virtue in being evasive, or equivocating. There is also great skill. Any child can blurt out the truth, without thought to the consequences. It takes great maturity to appreciate the value of silence.

I think he’s right. But Radical Honesty isn’t altogether wrong, either. Let me be clear: Radical Honesty, as a lifestyle, is ridiculous and insane. Advocating telling the truth 100% of the time, no matter what, is harmful extremism. But it’s also wonderfully seductive as a concept, because it illustrates how needlessly afraid most of us are of truth – even truths that could potentially help us. Radical Honesty teaches us to be more brave. That is, when it’s not destroying our lives and the lives of everyone around us.

Ask yourself:

- What is the purpose of this truth?

- What effect will sharing this truth have on the other person, on yourself, on the world?

- What change will come about, positive or negative, from choosing to voice a particular truth at a particular time?

I believe the true lesson of Radical Honesty is that truth, real truth, is honesty with a purpose. Ideally a noble purpose, but any purpose at all other than “because I could” will suffice. By all means, be brave; embrace the truth. But if your honesty has no purpose, if you can’t imagine any positive outcome from being honest, I suggest you’re better off keeping it to yourself.

Or even lying.