That’s Not a Bug, It’s a Feature Request

For as long as I’ve been a software developer and used bug tracking systems, we have struggled with the same fundamental problem in every single project we’ve worked on: how do you tell bugs from feature requests?

Sure, there are some obvious crashes that are clearly bugs. But that’s maybe 10% of what you deal with on a daily basis, and the real killer showstopper bugs – the ones that prevent normal usage of the system – are eradicated quickly, lest the entire project fail. The rest of the entries in your bug tracking system, the vast majority, exist in an uncertain gray no-man’s land. Did users report a bug? Not quite. Are users asking for a new or enhanced feature? Not quite. Well, which is it?

It’s an insoluble problem. Furthermore, I think most bug tracking systems fail us because they make us ask the wrong questions. They force you to pick a side. Hatfields vs. McCoys. Coke vs. Pepsi. Bug vs. Feature Request. It’s a painful and arbitrary decision, because most of the time, it’s both. There’s no difference between a bug and a feature request from the user’s perspective. If you want to do something with an application (or website) and you can’t do it because that feature isn’t implemented – how is that any different than not being able to do something due to an error message?

Consider an example: Visual Studio doesn’t use the correct font when building Windows applications. Is this a bug or a feature request?

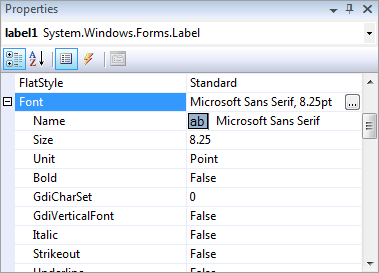

Personally, I consider this a bug. I guess Microsoft does too, at least in theory, because it’s been in Microsoft’s Connect bug tracking system for over four years now. When you build a Windows application, wouldn’t you expect it to use the default font of the underlying operating system you’re running it on, unless you’ve explicitly told it otherwise? Well, guess what happens when you create a new form in Visual Studio 2008 and instantiate a label control.

Party like it’s 1996, folks, because you’ll get MS Sans Serif, and you’ll like it. That is the default for each new form. Never mind that every new application you build will look like – let me put this as delicately as I can – ass.

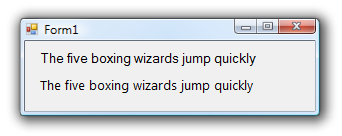

Here’s a comparison of a label with the default font, versus one that was explicitly set to the default GUI font.

Judging by the applications I’ve used, most Windows developers couldn’t care less about design. That’s bad. What’s even worse is learning that same design carelessness has shipped in the box with every copy of Visual Studio since 2002.

Of course, matters of design are so subjective. If only there were some definitive source we could refer to on the matter of proper Windows GUI font usage. Some sort of reference standard, as it were. Like, say, the top rules for Windows Vista User Experience from Microsoft:

- Use the Aero Theme and System Font (Segoe UI)

- Use common controls and common dialogs

- Use the standard window frame, use glass judiciously

There are 12 rules in total, but the rule I’m looking for is right at the top – applications should use the system font.

The hilarity of this list is already sort of self evident, given that I’ve written an entire post bemoaning the general lack of fit and finish in Windows Vista. I couldn’t help but laugh at rule number 12: Reserve time for “fit and finish!” Now there’s a rule Microsoft should have taken to heart while developing Windows Vista. Understand this is all coming from a guy who likes Vista.

But I digress.

Despite the windows forms font behavior in Visual Studio 2008 contradicting rule number one of Microsoft’s own design guidelines, this “bug” has gone unfixed for over four years. It has been silently reclassified as a “feature request” and effectively ignored. Nothing’s broken, after all: using the wrong font hasn’t caused any application crashes or lost productivity. On the other hand, imagine how many BigCorpCo apps have been built since then that violate Microsoft’s own design rules for their platform. Either because the developers didn’t realize that the app font didn’t match the operating system, or because they didn’t have the time to write the workaround code necessary to make it do the right thing.

Yes, this is a small thing. And I’m sure fixing it wouldn’t result in selling an additional umpteen thousand Visual Studio licenses to BigCorpCo, which is why it hasn’t happened yet.

But the question remains: is this a bug, or a feature request?

One of my favorite things about UserVoice – which we use for Stack Overflow – is the way it intentionally blurs the line between bugs and feature requests. Users never understand the difference anyway, and what’s worse, developers tend to use that division as a wedge against users. Nudge things you don’t want to do into that “feature request” bucket, and proceed to ignore them forever. Argue strongly and loudly enough that something reported as a “bug” clearly isn’t, and you may not have to to do any work to fix it. Stop dividing the world into Bugs and Feature Requests, and both of these project pathologies go away.

I wish we could, as an industry, spend less time fighting tooth and nail over definitions, painstakingly placing feedback in the “bug” or “feature request” buckets – and more time doing something constructive with our users’ feedback.