James Bach responded to my recent post, Are You Following the Instructions on the Paint Can?, with Studying Jeff Atwood's Paint Can.

Being under Bach's intensive analytical microscope feels a lot like an interview with Hannibal Lecter. It's flattering, but it's also a little scary. You learn a tremendous number of things about yourself – at the risk of your professional dignity, and maybe even your soul.

In a previous entry, I complained about the fact that Bach's blog doesn't allow comments. Some readers took this as a personal attack on James. Nothing could be further from the truth. I've been meaning to write about that topic for months, and James' blog just happened to be the most recent case. I have tremendous respect for Bach and the way he aggressively questions convention. Prior to this paint can dialog, I had already based two blog entries on his writing: It's Better Than Nothing and Best Practices and Puffer Fish. If anything, we should form a mutual admiration society.

Now that I've gotten all the disclaimers out of the way, I can respond to the actual content of Mr. Bach's entry. First, I want to give James credit for identifying a key assumption:

"What I find particularly interesting is that none of the mistakes on this checklist have anything to do with my skill as a painter."

I think what Jeff meant to say [here] is that they have nothing to do with what he recognizes as his skill as a painter. I would recognize these mistakes, assuming for the moment that they are mistakes, as being strongly related to his painting skill. Perhaps since I don't have any painting skill, it's easier for me to see it than for him. Or maybe he means something different by the idea of skill than I do. (I think skill is an improvable ability to do something) Either way, there's nothing slam dunk obvious about his point. I don't see how it can be just a matter of "read the instructions stupid."

This is dead on. I used to run a painting business in college. So my idea of "painting skill" – for the record, it's how cleanly and evenly you physically apply a coat of paint to the surface – is quite different than James'. If you read any of his writing, you'll quickly determine Mr. Bach is incredibly effective at sussing out all the assumptions you're making that you don't realize you're making. And questioning assumptions is a tremendously powerful method of investigation, particularly when someone helps you identify the ones that you're blind to.

Beyond that, the general thrust of Bach's reply is that instructions aren't always helpful:

Consider all the instructions you encounter and do not read. Consider the software you install without reading the "quickstart" guide. Consider the clickwrap licenses you don't read, or the rental cars you drive without ever consulting the drivers manual in states where you have not studied the local driving laws. Consider the doors marked push that you pull upon. Consider the shampoo bottle that says "wash, rinse, repeat." Well, I have news for the people who make Prell: I don't repeat. Did you hear me? I don't repeat.

I would have to say that most instructions I come across are unimportant and some are harmful. Most instructions I get about software development process, I would say, would be harmful if I believed them and followed them. Most software process instructions I encounter are fairy tales, both in the sense of being made up and in the sense of being cartoonish. Some things that look like instructions, such as "do not try this at home" or "take out the safety card and follow along," are not properly instructions at all, they are really just ritual phrases uttered to dispel the evil spirits of legal liability. Other things that really are instructions are too vague to follow, such as "use common sense" or "be creative" or "follow the instructions."

There are, of course, instructions I could cite that have been helpful to me. I saw a sign over a copy room that said "Do not use three hole paper in this copy machine... unless you want it to jam." and one next to it that said "Do not use the Microwave oven while making copies... unless you want the fuse to blow." I often find instructions useful when putting furniture together; and I find signs at airports generally useful, even though I have occasionally been steered wrong.

Instructions can be useful, or useless, or something in between. Therefore, I propose that we each develop a skill: the skill of knowing when, where, why and how to follow instructions in specific contexts. Also, let's develop the skill of giving instructions.

Although I absolutely agree that you must be critical of everything you read, James' statement that "instructions can be useful, useless, or something in between" is just as unhelpful as my "for best results, follow the instructions" advice. I implicitly assumed that the person reading the instructions on the paint can was smart enough to read those instructions as suggestions, reminders, and guidelines – not as a recipe to be slavishly followed to the letter.

I agree with Bach's assertion that a paint can is neither a supervisor, nor a mentor, nor a judge of quality. A static list of instructions is no substitute for hands-on help with your painting project from someone who has extensive painting experience.

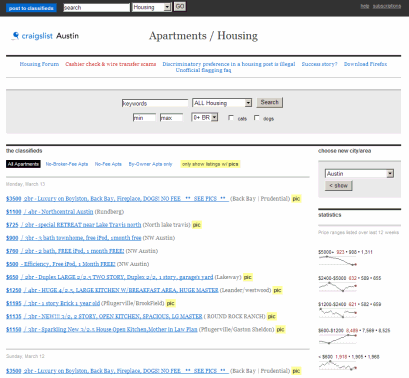

But you rarely have the luxury of working with experts. Most of the time, you're on your own, and the bulleted list is all you have. Consider this list of painting tips from John Montgomery. We had a problem a few days ago while painting. Our latex paint was drying exceptionally fast on the second coat and causing problems with the smoothness of the finish. Because I had read John's painting tips, I remembered this bullet point from his list:

Mix your paint and add Flotrol. If you're more than 24 hours from the paint store, open your paint and mix it. You should also add Flotrol (latex) or Penetrol (oil) to it – these paint conditioners don't thin the paint or change its color, but they do affect how smoothly it goes on and limit brush and roller stroke evidence.

I went to the store, bought some Flotrol, mixed it in, and our problem was solved.

It's doubtful I would have been able to fix this problem if I hadn't followed at least some of the instructions on John's blog. Although I agree with James Bach's central point – you should question everything you read – I sort of assumed everyone does this already. Maybe I assume too much. But sometimes a bulleted list of instructions sure does come in handy.

Discussion