Filesystems Aren’t a Feature

Don Park recently made an interesting observation about how his family uses the computer:

When I observe how my wife and son uses the family computer, I can’t help noticing how little use they have for the desktop. They look bewildered when I open the Windows Explorer. To them, file open or file save dialog is where the files go. My Documents? It’s just an icon they never touch.

I’ve observed the same filesystem phobia many times in many different users, including my wife. When you observe the same problem across so many users, you have to wonder – isn’t the real problem the filesystem itself? Jef Raskin has a lot to say about this in The Humane Interface, starting with filenames:

File names are bothersome when you are about to save work, because you have to stop in the middle of your activity, which is trying to store your work away, and invent a file name. Creating names is an onerous task: you are required to invent, on the spot and in a few moments, a name that is unique, memorable, and within the naming conventions of the filesystem you are using. At that moment, the question of a file name is not your locus of attention; preserving your work is.

File names are also a nuisance when you have to retrieve a file. The name you thought up was probably not particularly memorable, and you probably forgot it after a few weeks (or less). I for one, can rarely remember a file name unless it is quite recent. Even looking through lists of filenames is frustrating. Just what is in that file labeled “notes ybn 32?” The name seemed so clever and memorable when I created it. Then, too, many files are nearly the same. How many different, creative, readily remembered names can you think up for letters to your accountant about last year’s taxes? Filing them by date may be useful, but how many of us remember that the letter about the deduction for the company truck was written on August 14?

Raskin’s modest proposal to solve this conundrum is nothing less than the complete elimination of the filesystem:

There should be no distinction between a file name and a file. A human mind can more effectively use a fast, whole-text search engine, so that any word or phrase from the file can serve as a key to it. (Eventually, we’d want more: a request for “a letter about dragonflies” would [search] for something that had the form of a letter and looked not only for the word dragonfly but also related terms and expressions, such as Odonata – in case dragonflies had been referred to by their scientific name – and if no instances of such letters were found, the search would look for nonletter documents, and so forth, extending out to networked computers and the internet.) You do not remember the content of “Letter 12/21/92 to Jim” when you see that title, but you do remember that you once wrote to Jim about the blue Edsel that ran across your eyeglasses. A search on Edsel is likely to find only one or two entries on your whole system– unless you are an Edsel fancier, in which case you would probably choose another pattern on which to search. An unlimited length file name is a file. The content of a text file is its own best name.

Raskin actually shipped products that lacked filesystems entirely in the mid 80s – the standalone Canon Cat and the Apple //e add-in card version, the SwyftCard. Both were critical if not popular successes:

This discussion is not theoretical: on the SwyftWare and Canon Cat products, the elimination of file names, directories, and the various mechanisms usually provided for manipulating them proved one of their most successful features.

I remember reading about the SwyftCard when I was a teenage Apple //c owner and not quite comprehending what it was, or what it did. Like the Canon Cat, it was clearly far ahead of its time– maybe too far ahead to sell. If you’re curious about the LEAP interface used in both products, there’s a Windows port called “Archy” available at the Raskin Center.

Raskin isn’t the only notable UI figure to have serious misgivings about the filesystem, though. Alan Cooper derides it for an entire chapter of About Face, Rethinking Files and Save:

The implementation model of the file system runs contrary to the mental model almost all users bring to it. Most users picture electronic files like printed documents in the real world, and they imbue them with the behavioral characteristics of these real objects. Users visualize two salient facts about all documents: First, there is only one document; and second, it belongs to them. The file system’s implementation model violates both of these rules. There are always two copies of the document, and they both belong to the program.

Every data file, every document, and every program, while in use by the computer, exists in two places at once: on disk and in main memory. The user, however, imagines his document as a book on a shelf. Let’s say it is a journal. Occasionally, it comes down off the shelf to have something added to it. There is only one journal, and it either resides on the shelf or it resides in the user’s hands. On the computer, the disk drive is the shelf, and main memory is the place where editing takes place, equivalent to the user’s hands. But in the computer world, the journal doesn’t come off the shelf. Instead a copy is made, and that copy is what resides in computer memory. As the user makes changes, he is actually making changes to the copy in memory, while the original remains untouched on disk. When the user is done and closes the document, the program is faced with a decision: whether to replace the original on disk with the changed copy from memory, or to discard the altered copy. From the programmer’s point of view, equally concerned with all possibilities, this choice could go either way. From the software’s implementation model point of view, the choice is the same either way. However, from the user’s point of view, there is no decision to be made at all. He just made his changes and now he is just putting the document away. If this were happening with a paper journal in the physical world, the user would have pulled it off the shelf, penciled in some additions, and then replaced it on the shelf. It’s as if the shelf were to speak up, asking him if he really wants to keep those changes!

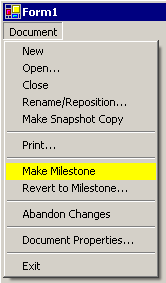

Alan proposes a less radical solution than Jef: instead of doing away with the filesystem, do everything you can to hide it from the user. This includes automatic saving with no prompts, automatic versioning, etcetera. The end result is a rebranded File menu:

Cooper closes the chapter with a single design tip: disks are a hack, not a design feature. We can’t afford computers with 50 gigabytes of non-volatile main memory, so hard drives and filesystems are a necessity for permanent storage. But just because us programmers are stuck with the annoying two-copy filesystem model doesn’t mean we have to mindlessly subject users to it, either.