An Inalienable Right to Privacy

Privacy has always been a concern on the internet. But as more and more people let it all hang out on the many social networking websites popping up like weeds all over the web, there’s much more at risk. Every other week, it seems, I’m reading about some new privacy gaffe. Last month, it was Facebook’s Beacon opt-out policy; this week, it’s Google Reader sharing private data. The privacy problems just keep piling up as more people tune in and turn on.

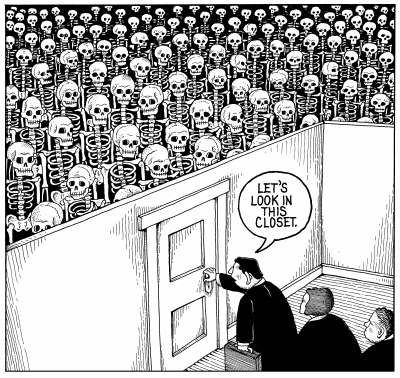

Nearly a decade ago, Sun Microsystems CEO Scott McNealy snapped out a warning to the worriers of the Internet Age: “You don’t have any privacy. Get over it.” McNealy’s words look more prescient every year. In 2006, AOL unwittingly divulged the personal lives of 650,000 customers by publishing their search histories as research data. Despite AOL’s attempts to anonymize the info, the New York Times quickly outed a 62-year-old lady in Georgia whose searches revealed her dog was wetting the upholstery. The Justice Department has subpoenaed Google, Yahoo!, MSN, and AOL for lists of search queries. More recently, Facebook employees were caught reading the customer logs.

Nothing warms the cockles of a user’s heart quite like the tender mercies of your friendly neighborhood CEO. That privacy stuff you’re so worried about? Get over it! You might wonder if Mr. McNealy has the same glib attitude towards the privacy of himself and his own family. Only criminals have stuff to hide, right? Here’s Bruce Schneier’s take on the value of privacy:

Last week, revelation of yet another NSA surveillance effort against the American people has rekindled the privacy debate. Those in favor of these programs have trotted out the same rhetorical question we hear every time privacy advocates oppose ID checks, video cameras, massive databases, data mining, and other wholesale surveillance measures: “If you aren’t doing anything wrong, what do you have to hide?”

Some clever answers: “If I’m not doing anything wrong, then you have no cause to watch me.” “Because the government gets to define what’s wrong, and they keep changing the definition.” “Because you might do something wrong with my information.” My problem with quips like these – as right as they are – is that they accept the premise that privacy is about hiding a wrong. It’s not. Privacy is an inherent human right, and a requirement for maintaining the human condition with dignity and respect.

I promote openness and making things public. Not everything, of course; just the good and publicly useful sections you’ve culled from the repertoire of your life. If you don’t consider any part of your life worthy of public consumption in any form, are you really doing anything?

Even as a proponent of selectively exhibiting parts of your life in public, there’s a huge part of my life that’s private. I didn’t realize it, but I’ve relied on privacy through obscurity until now. My life is so utterly mundane that I can’t imagine anyone caring what I do, what I buy, what I read, and who I talk to. I thought privacy was overrated. I certainly never considered privacy a basic human right, on par with life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. But it is.

Too many wrongly characterize the debate as “security versus privacy.” The real choice is liberty versus control. Tyranny, whether it arises under threat of foreign physical attack or under constant domestic authoritative scrutiny, is still tyranny. Liberty requires security without intrusion, security plus privacy. Widespread police surveillance is the very definition of a police state. And that’s why we should champion privacy even when we have nothing to hide.

If power corrupts, then access to a pure, unfettered stream of data on every American corrupts absolutely. The default strategy of privacy through obscurity may have worked by default in the hodepodge, sporadically digital worlds of the 80s and 90s. Not any more. Now that so much of the world is online or stored in a vast database somewhere, all those tiny digital artifacts of who you are and what you do can be woven into a complete tapestry of your life. And you better believe it will be, because it makes some people a lot of money.

So what can we do about it? Is privacy possible in the digital age?

The truth is, fighting to protect privacy is a quixotic venture. Sure, there are any number of technologies, techniques and work-arounds you can employ, all in the effort to protect your privacy. But such a quest is like trying to dig a hole in middle of a fast flowing river. The rich and powerful gain some amount of privacy only because they can afford to grid their personal lives with a kind of digital body armor.

Garfinkel says we need to rethink privacy in the 21st Century. “It’s not about the man who wants to watch pornography in complete anonymity over the Internet. It’s about the woman who’s afraid to use the Internet to organize her community against a proposed toxic dump - afraid because the dump’s investors are sure to dig through her past if she becomes too much of a nuisance.”

I’m with Bruce on this one. Demand privacy even if you don’t think you need it. Consider that the next time you sign up for some new social networking service, or a grocery discount card, or give out your telephone or social security number for some trivial reason. Neglecting to protect our right to privacy is, in effect, giving up on privacy altogether. And that’s not a world I want to live in. Openness is important – but so is privacy, in equal measure. I believe we can have both, but not without active effort on our part.