This weekend, the Gawker network was compromised.

This weekend we discovered that Gawker Media's servers were compromised, resulting in a security breach at Lifehacker, Gizmodo, Gawker, Jezebel, io9, Jalopnik, Kotaku, Deadspin, and Fleshbot. If you're a commenter on any of our sites, you probably have several questions.

It's no Black Sunday or iPod modem firmware hack, but it has release notes – and the story it tells is as epic as Beowulf:

So, here we are again with a monster release of ownage and data droppage. Previous attacks against the target were mocked, so we came along and raised the bar a little. How's this for "script kids"? Your empire has been compromised, your servers, your databases, online accounts and source code have all been ripped to shreds!

You wanted attention, well guess what, You've got it now!

Read those release notes. It'll explain how the compromise unfolded, blow by blow, from the inside.

Gawker is operated by Nick Denton, notorious for the unapologetic and often unethical "publish whatever it takes to get traffic" methods endorsed on his network. Do you remember the iPhone 4 leak? That was Gawker. Do you remember the article about bloggers being treated as virtual sweatshop workers? That was Gawker. Do you remember hearing about a blog lawsuit? That was probably Gawker, too.

Some might say having every account on your network compromised is exactly the kind of unwanted publicity attention that Gawker was founded on.

Personally, I'm more interested in how we can learn from this hack. Where did Gawker go wrong, and how can we avoid making those mistakes on our projects?

- Gawker saved passwords. You should never, ever store user passwords. If you do, you're storing passwords incorrectly. Always store the salted hash of the password – never the password itself! It's so easy, even members of Mensa er … can't … figure it out.

- Gawker used encryption incorrectly. The odd choice of archaic DES encryption meant that the passwords they saved were all truncated to 8 characters. No matter how long your password actually was, you only had to enter the first 8 characters for it to work. So much for choosing a secure pass phrase. Encryption is only as effective as the person using it. I'm not smart enough to use encryption, either, as you can see in Why Isn't My Encryption.. Encrypting?

- Gawker asked users to create a username and password on their site. The FAQ they posted about the breach has two interesting clarifications:

2) What if I logged in using Facebook Connect? Was my password compromised?

No. We never stored passwords of users who logged in using Facebook Connect.

3) What if I linked my Twitter account with my Gawker Media account? Was my Twitter password compromised?

No. We never stored Twitter passwords from users who linked their Twitter accounts with their Gawker Media account.That's right, people who used their internet driver's license to authenticate on these sites had no security problems at all! Does the need to post a comment on Gizmodo really justify polluting the world with yet another username and password? It's only the poor users who decided to entrust Gawker with a unique username and 'secure' password who got compromised.

(Beyond that, "don't be a jerk" is good advice to follow in business as well as your personal life. I find that you generally get back what you give. When your corporate mission is to succeed by exploiting every quasi-legal trick in the book, surely you can't be surprised when you get the same treatment in return.)

But honestly, as much as we can point and laugh at Gawker and blame them for this debacle, there is absolutely nothing unique or surprising about any of this. Regular readers of my blog are probably bored out of their minds by now because I just trotted out a whole bunch of blog posts I wrote 3 years ago. Again.

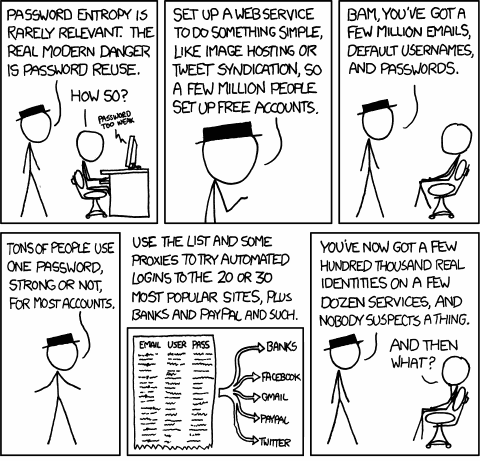

Here's the dirty truth about website passwords: the internet is full of websites exactly like the Gawker network. Let's say you have good old traditional username and passwords on 50 different websites. That's 50 different programmers who all have different ideas of how your password should be stored. I hope for your sake you used a different (and extremely secure) password on every single one of those websites. Because statistically speaking, you're screwed.

In other words, the more web sites you visit, the more networks you touch and trust with a username and password combination – the greater the odds that at least one of those networks will be compromised exactly like Gawker was, and give up your credentials for the world to see. At that point, unless you picked a strong, unique password on every single site you've ever visited, the situation gets ugly.

The bad news is that most users don't pick strong passwords. This has been proven time and time again, and the Gawker data is no different. Even worse, most users re-use these bad passwords across multiple websites. That's how this ugly Twitter worm suddenly appeared on the back of a bunch of compromised Gawker accounts.

Now do you understand why I've been so aggressive about promoting the concept of the internet driver's license? That is, logging on to a web site using a set of third party credentials from a company you can actually trust to not be utterly incompetent at security? Sure, we're centralizing risk here to, say, Google, or Facebook – but I trust Google a heck of a lot more than I trust J. Random Website, and this really is no different in practice than having password recovery emails sent to your GMail account.

I'm not here to criticize Gawker. On the contrary, I'd like to thank them for illustrating in broad, bold relief the dirty truth about website passwords: we're all better off without them. If you'd like to see a future web free of Gawker style password compromises – stop trusting every random internet site with a unique username and password! Demand that they allow you to use your internet driver's license – that is, your existing Twitter, Facebook, Google, or OpenID credentials – to log into their website.