One of the items we're struggling with now on Stack Overflow is how to maintain near-instantaneous performance levels in a relational database as the amount of data increases. More specifically, how to scale our tagging system. Traditional database design principles tell you that well-designed databases are always normalized, but I'm not so sure.

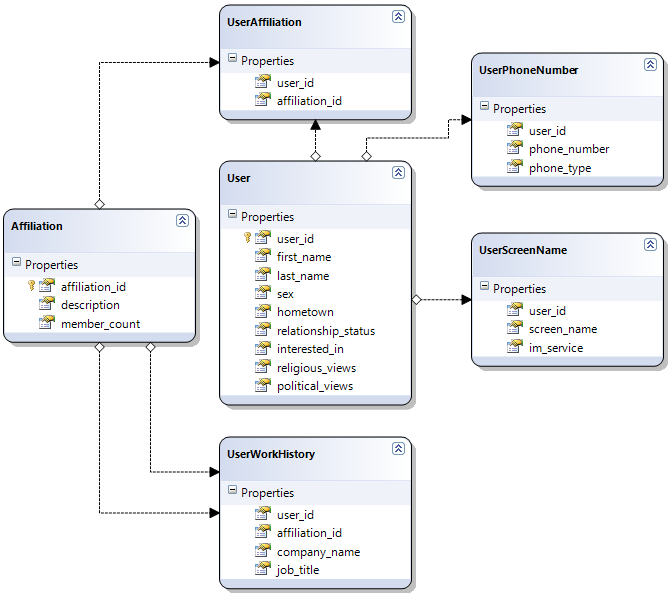

Dare Obasanjo had an excellent post When Not to Normalize your SQL Database wherein he helpfully provides a sample database schema for a generic social networking site. Here's what it would look like if we designed it in the accepted normalized fashion:

Normalization certainly delivers in terms of limiting duplication. Every entity is represented once, and only once -- so there's almost no risk of inconsistencies in the data. But this design also requires a whopping six joins to retrieve a single user's information.

select * from Users u inner join UserPhoneNumbers upn on u.user_id = upn.user_id inner join UserScreenNames usn on u.user_id = usn.user_id inner join UserAffiliations ua on u.user_id = ua.user_id inner join Affiliations a on a.affiliation_id = ua.affiliation_id inner join UserWorkHistory uwh on u.user_id = uwh.user_id inner join Affiliations wa on uwh.affiliation_id = wa.affiliation_id

(Update: this isn't intended as a real query; it's only here to visually illustrate the fact that you need six joins -- or six individual queries, if that's your cup of tea -- to get all the information back about the user.)

Those six joins aren't doing anything to help your system's performance, either. Full-blown normalization isn't merely difficult to understand and hard to work with -- it can also be quite slow.

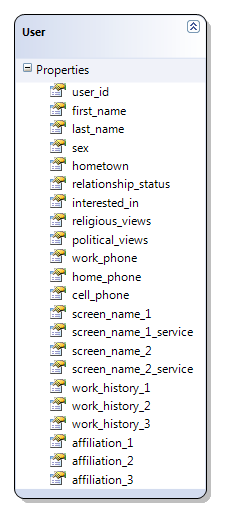

As Dare points out, the obvious solution is to denormalize -- to collapse a lot of the data into a single Users table.

This works -- queries are now blindingly simple (select * from users), and probably blindingly fast, as well. But you'll have a bunch of gaping blank holes in your data, along with a slew of awkwardly named field arrays. And all those pesky data integrity problems the database used to enforce for you? Those are all your job now. Congratulations on your demotion!

Both solutions have their pros and cons. So let me put the question to you: which is better -- a normalized database, or a denormalized database?

Trick question! The answer is that it doesn't matter! Until you have millions and millions of rows of data, that is. Everything is fast for small n. Even a modest PC by today's standards -- let's say a dual-core box with 4 gigabytes of memory -- will give you near-identical performance in either case for anything but the very largest of databases. Assuming your team can write reasonably well-tuned queries, of course.

There's no shortage of fascinating database war stories from companies that made it big. I do worry that these war stories carry an implied tone of "I lost 200 pounds and so could you!"; please assume the tiny-asterisk disclaimer results may not be typical is in full effect while reading them. Here's a series that Tim O'Reilly compiled:

- Second Life

- Blogline and Memeorandum

- Flickr

- NASA World Wind

- Craigslist

- O'Reilly Research

- Google File System and BigTable

- Findory and Amazon

- MySQL

There's also the High Scalability blog, which has its own set of database war stories:

First, a reality check. It's partially an act of hubris to imagine your app as the next Flickr, YouTube, or Twitter. As Ted Dziuba so aptly said, scalability is not your problem, getting people to give a shit is. So when it comes to database design, do measure performance, but try to err heavily on the side of sane, simple design. Pick whatever database schema you feel is easiest to understand and work with on a daily basis. It doesn't have to be all or nothing as I've pictured above; you can partially denormalize where it makes sense to do so, and stay fully normalized in other areas where it doesn't.

Despite copious evidence that normalization rarely scales, I find that many software engineers will zealously hold on to total database normalization on principle alone, long after it has ceased to make sense.

When growing Cofax at Knight Ridder, we hit a nasty bump in the road after adding our 17th newspaper to the system. Performance wasn't what it used to be and there were times when services were unresponsive.A project was started to resolve the issue, to look for 'the smoking gun'. The thought being that the database, being as well designed as it was, could not be of issue, even with our classic symptom being rapidly growing numbers of db connections right before a crash. So we concentrated on optimizing the application stack.

I disagreed and waged a number of arguments that it was our database that needed attention. We first needed to tune queries and indexes, and be willing to, if required, pre-calculate data upon writes and avoid joins by developing a set of denormalized tables. It was a hard pill for me to swallow since I was the original database designer. Turned out it was harder for everyone else! Consultants were called in. They declared the db design to be just right - that the problem must have been the application.

After two months of the team pushing numerous releases thought to resolve the issue, to no avail, we came back to my original arguments.

Pat Helland notes that people normalize because their professors told them to. I'm a bit more pragmatic; I think you should normalize when the data tells you to:

- Normalization makes sense to your team.

- Normalization provides better performance. (You're automatically measuring all the queries that flow through your software, right?)

- Normalization prevents an onerous amount of duplication or avoids risk of synchronization problems that your problem domain or users are particularly sensitive to.

- Normalization allows you to write simpler queries and code.

Never, never should you normalize a database out of some vague sense of duty to the ghosts of Boyce-Codd. Normalization is not magical fairy dust you sprinkle over your database to cure all ills; it often creates as many problems as it solves. Fear not the specter of denormalization. Duplicated data and synchronization problems are often overstated and relatively easy to work around with cron jobs. Disks and memory are cheap and getting cheaper every nanosecond. Measure performance on your system and decide for yourself what works, free of predispositions and bias.

As the old adage goes, normalize until it hurts, denormalize until it works.